Roger Rabbit - Disney's Doomed, Marooned Toon

Who Banished--nay, Erased--the Hapless Rabbit?

Roger Rabbit and a Dithering Disney's Last Chance for Relevancy

Ironically, Roger Rabbit almost never happened. The blundering bunny saved Disney, buying the company clout, credibility, and most importantly--time--as its "Disney Renaissance" loomed and bloomed just a year or two beyond. But as Disney's comeback came...the rabbit's popularity began to wane.

The 1980s was a time of creative crossroads. Disney was suffering from a decade’s-long lull, facing irrelevancy as inspiration waned and profits sagged. Worse, the art of animation itself had stagnated; what had become the symbol of artistic freedom and unfettered imagination had been reduced to small budgets and small screens. The Saturday morning and after-school cartoon, in other words—productions more synonymous with commercial banality than poetic expression.

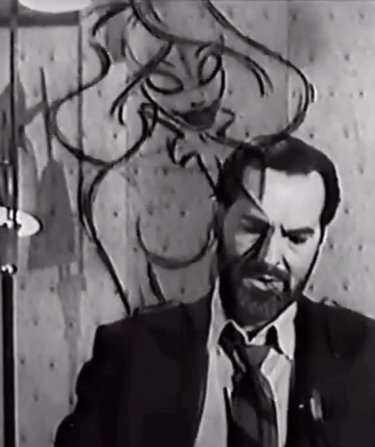

At the same time, a young Steven Spielberg, already famous for directing blockbusters like Jaws and Indiana Jones, hoped to explore animation as another form of cinematic vehicle. He had the passion, clout, and power…lacking only the “how.” Despite his talents, could he—dared he—enter a domain already so dominated by the likes of Disney and Hanna-Barbera? And then came his white rabbit of a chance; Disney was looking for a financial backer to help buoy the rising costs of its Roger Rabbit hybrid live-action/animated film. For Spielberg, it was the perfect opportunity.

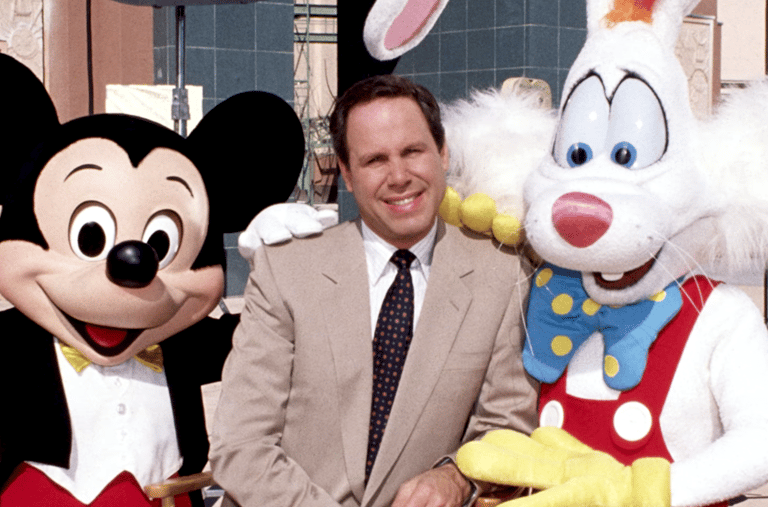

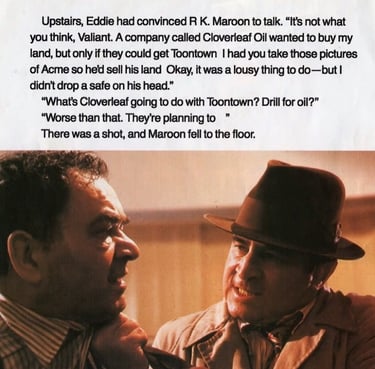

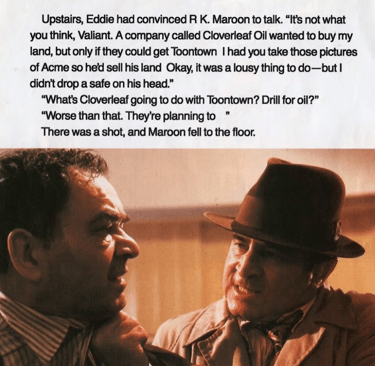

Based on the 1981 book Who Censored Roger Rabbit, Disney had purchased the character and concept rights only to then dither over what to do with them. Incoming CEO Michael Eisner knew the property had merit, however; it just needed the right visionary, the correct direction, and a lot more cash than Disney was willing to afford. Spielberg, along with his studio Amblin Entertainment, was exactly what the rabbit needed.

Who Framed Roger Rabbit, more than being a silly comedy about a cartoon rabbit framed for murder, became a tribute to the golden age of animation. A fan-boy’s showcase of that bygone age’s eccentric sensibilities. A demonstration, and reminder, of what made the classic cartoon short so timeless, so great.

After enormous production costs and difficulty, the movie achieved its every directive, both succeeding at the box office and enthralling even the most incredulous critic. And yet, as time passed—as the film cycled from theaters to video to TV…and eventually, to niche home libraries and fuzzy memories…Roger Rabbit became less an homage and more a last hurrah to that classical, hand-drawn age. The movie came to signify Animation’s storied past more than its future. Roger Rabbit, despite all the praise and accolades his movie received, would eventually vanish like so many of the old cartoon shorts he was designed to revive.

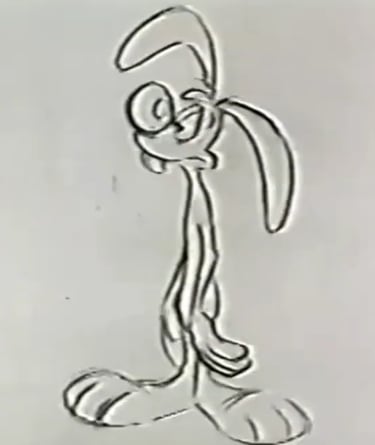

Roger Rabbit, before Spielberg's involvement, was a rather different creature. Although still a rabbit framed for murder, his persona, along with his co-stars', was very different.

Spielberg (Executive Producer), Zemeckis (Director), and Eisner (Disney CEO) were the acting triumvirate behind the film's existence. Without any one of them, the movie either wouldn't have been made, would have failed, or, at the very least, would have been very different.

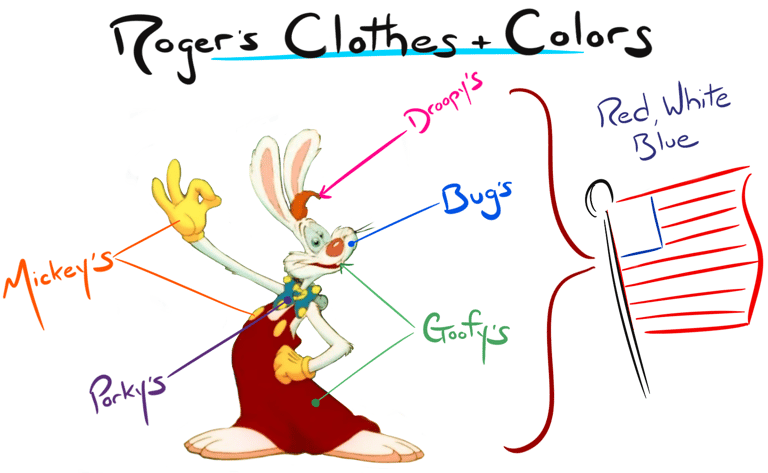

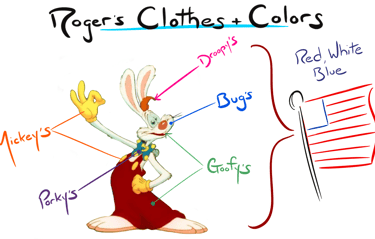

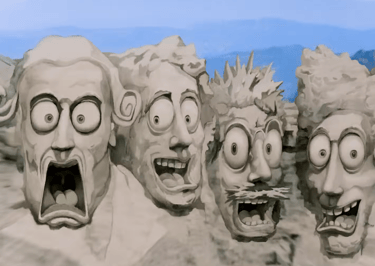

Roger's design is an amalgamation--a composite--of other popular toons' features...plus the American flag, which was used in the hopes of endearing the rabbit subconsciously to a predominately American audience.

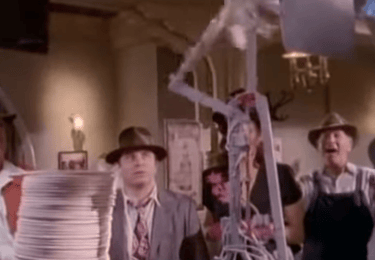

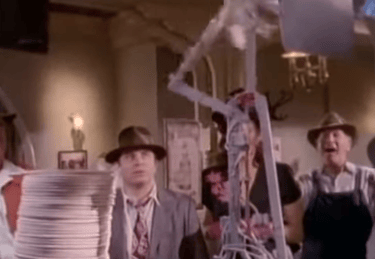

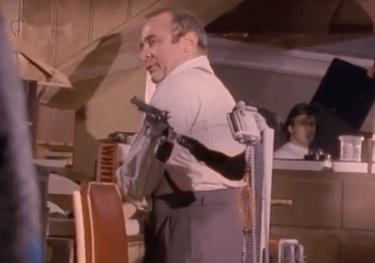

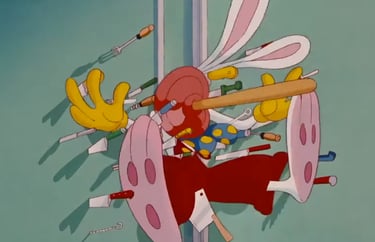

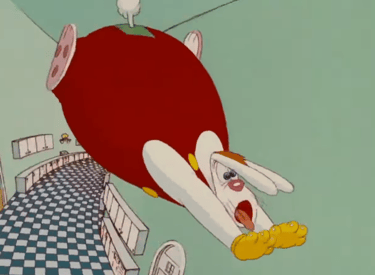

Who Framed Roger Rabbit was a complicated mix of live-action, animation, mannequin, bunny suit, and even remote controlled robotics. The one tool not used was CGI.

Why a Roger Rabbit 2 Proved Even Harder to Produce...

Who Framed Roger Rabbit isn’t an obscure film. It’s not abandoned and certainly not “dissed” by Disney, its lord and holder. But the character of Roger, that wacky rabbit fused with the goofiness of Goofy and the zanier early years of Daffy Duck, is no longer held with much esteem. Once the hopeful icon for a company just starting to rediscover itself, the character became all but buried by the renaissance it helped ignite.

Why? The reasons are a complicated mix of money and logistics, with a “Roger Rabbit 2” consuming a huge investment in both. It’d be expensive, take a long time to make, and moreover, would audiences even care once the sequel (or prequel, as the case may be) finally hit screens?

But ironically, the biggest obstacle was Steven Spielberg himself. Though his partnership with Disney saved the film from certain dissolution, now that the movie had become a hit…the visionary’s involvement had become a nuisance. As the co-copyright holder for the film and its newly-created characters, Spielberg was entitled to half the profits of anything Roger-related. Moreover, he reserved veto-rights to any Roger Rabbit initiative he didn’t agree with. Considering the artistic Spielberg/Amblin and profiteering Eisner/Disney were very different entities, this was a certain recipe for dysfunction. Not surprisingly, a second movie never materialized.

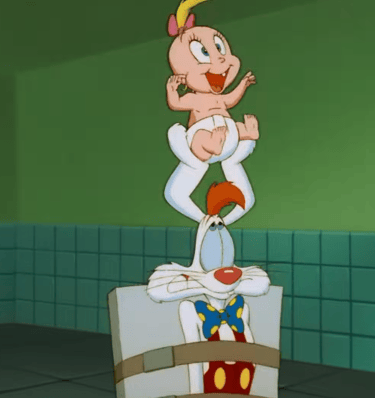

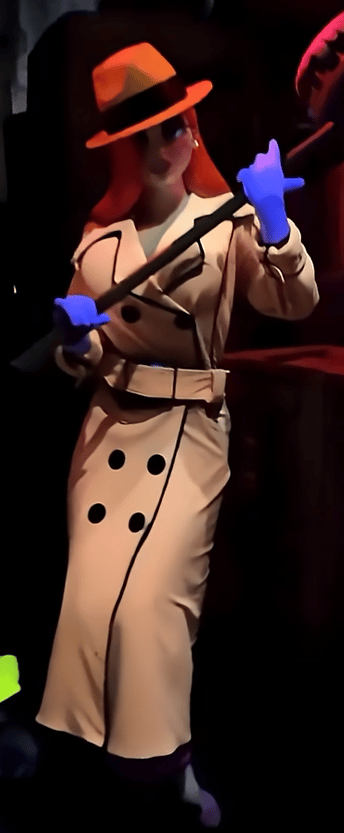

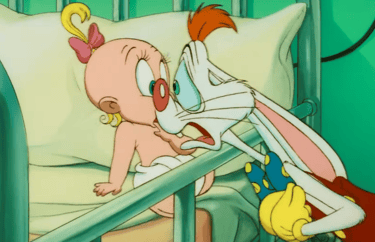

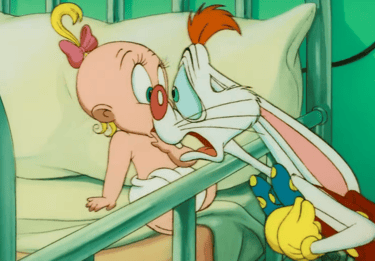

Over the years, Disney simply moved on. The so-called Disney Renaissance was making the company plenty of money, anyway, and Roger slowly became as faded as the golden age he portrayed. Worse, as long-time Disney execs and creatives became replaced by a more “socially-conscious” workforce (read: young politically-correct crusaders), secondary characters like the voluptuous Jessica Rabbit or foul-mouthed Baby Herman were seen as inappropriate, even unconscionable. No matter the satirical bent and intent of their original designs, 21st-century Disney didn’t care. These characters had to be cancelled. Or, better yet, never seen again.

Ultimately, Roger Rabbit never got its sequel. From “Toon Platoon,” a WW2 lampoon featuring a younger version of the toon, to “Who Discovered Roger Rabbit,” a more conventional origin story for the character, these would-be follow-ups never got made.

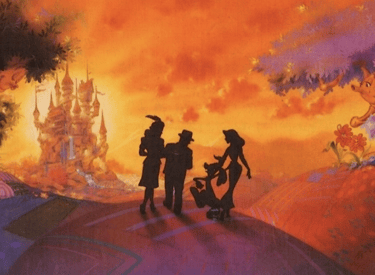

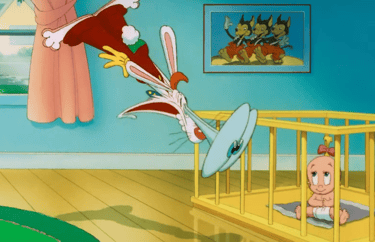

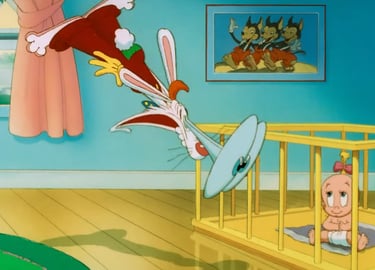

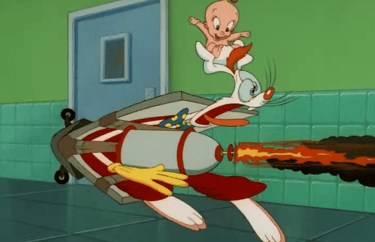

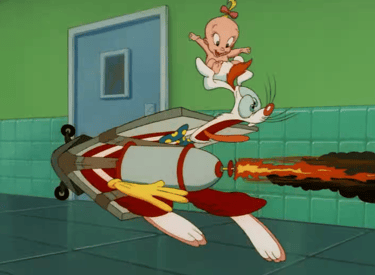

Why no Roger Rabbit 2? Simply, it was too taxing and expensive to make! The above stills from the first Roger Rabbit shows as much. In this scene's case, every frame of Jessica's sway and sashay had to be done four times--a composite of animation combined with layers of added flourish. In the uppermost image, Jessica's dress is flat and unadorned. By the fourth image, it's gained added depth, heft, and a glittery dimension.

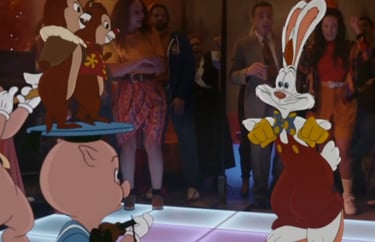

Roger Rabbit remains one of the few if only times certain toons appear on-screen together. Spielberg was largely the force behind getting the rights to these illustrious prizes. But scoring the same for the would-be sequel would be harder...and more expensive, a hurdle Disney wasn't eager to leap.

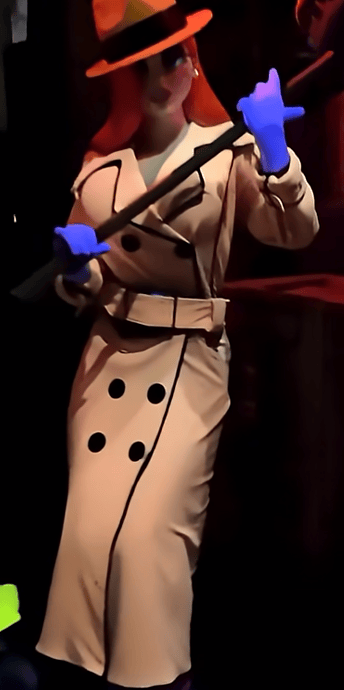

Although nearly as iconic as Roger himself, Jessica's decidedly politically incorrect nature has made her the ire of a currently ultra left-wing Disney. Even the DisneyLand ride Roger Rabbit's Car Toon Spin now has her absurdly covered in a trenchcoat.

But before that crushing disappointment—during those first few years after Roger Rabbit’s huge 1988 debut—the character seemed unstoppable. Ocean freighters of merchandise, endless park appearances, even a significant role in a TV special celebrating Mickey Mouse’s 60th birthday…the Rabbit remained a juggernaut through the 1980s’ closing days. To keep that Roger-coaster momentum alive and thriving—and really, to buy time for his hypothetical 1992 sequel—Disney and Spielberg agreed on releasing a plethora of high-quality shorts: Tummy Trouble, Rollercoaster Rabbit, and Trail Mix-up.

More were planned and all got canned. These three eight-minute pieces are the Rabbit’s last fragments of anything resembling a legacy.

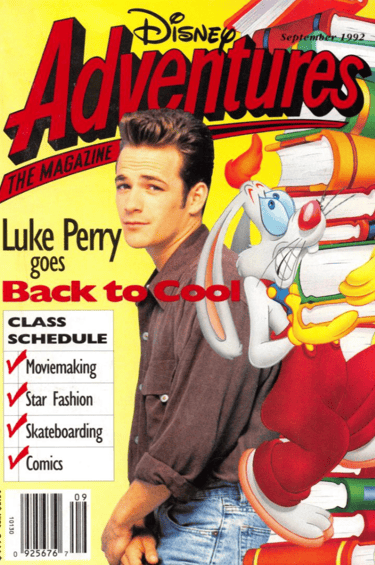

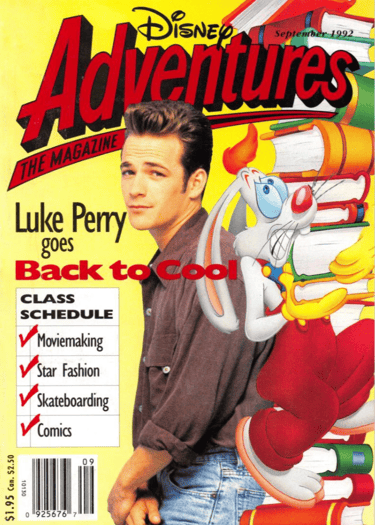

For a while, Roger was everywhere. In the parks, in comics, on TV (celebrating Mickey's 60th birthday, no less), even on the covers of popular magazines. But by 1995, the rabbit had largely vanished.

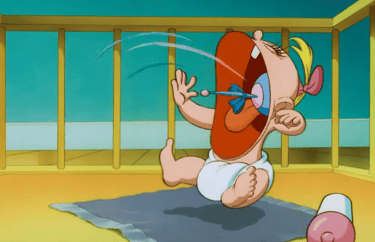

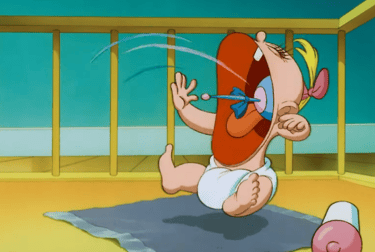

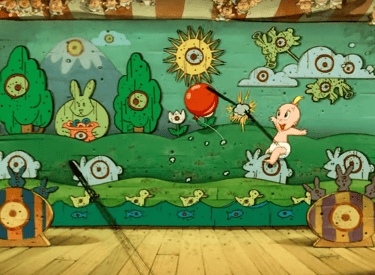

Before this so-called trilogy, however, the film Who Framed Roger Rabbit opened with its own spastic spectacle: a four-minute prelude coined Something’s Cookin’. The idea was to allow moviegoers, before the movie’s overarching plot kicked in, to experience Roger as a regular 1940s moviegoer would. Roger, perpetually saddled with the oblivious Baby Herman, was a hapless patsy earmarked for abuse in all the best gag-tastic and bombastic ways. The three-minute sprint gave context, in other words, to both Roger and his hybrid world of man and toon.

With the film’s success, Tummy Trouble looked to duplicate the formula. But extending the bite-sized Something’s Cooking hyperactive, uninterrupted energy into a more standard eight-minute short proved inevitably tricky. More than just pitting the baby against a bevy of kitchen appliances, a plot was now required. New venues. And something resembling an ending. More than just a proof of concept, more than being paired (and buoyed) by a human cast, Roger would now have to entertain the masses by his lonesome—carry the shenanigans by himself. Was he up to the task?

Indeed, Tummy Trouble and its two successors provide an intriguing glimpse into whether Roger Rabbit could have retained his household stardom beyond that initial film. At the time, Roger seemed poised to be another Mickey or Bugs Bunny. The question was one of sustainability: was Roger likable and dynamic enough to entertain beyond the frame of his singular film? These shorts help provide that answer.

Arguably, "Somethin's Cookin'" is the first (of four) Roger Rabbit shorts. Its sub 4-minute runtime, however, makes it more akin to a proof of concept meant to establish the Baby/Rabbit dynamic. It also set the tone for the three Roger toons to follow in terms of gag and narrative flow, plus the animators' obvious love for embellishing perspective.

The title cards for Roger's three fleeting shorts...

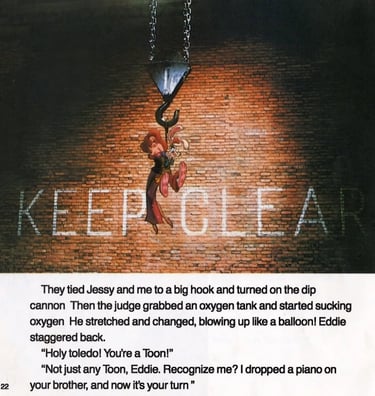

Roger Rabbit merchandise was everywhere in the late '80s, including this audio book of the movie re-adapted for kids (and voiced by Roger's actual voice actor, Charles Fleischer). The book, however, was forced to exclude any non-Disney character, emphasizing a point already made above: Ultimately, Roger Rabbit was held back by his toon guest stars versus being enhanced by them. The crossover gimmick became a liability later on.

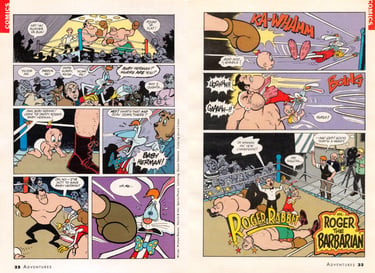

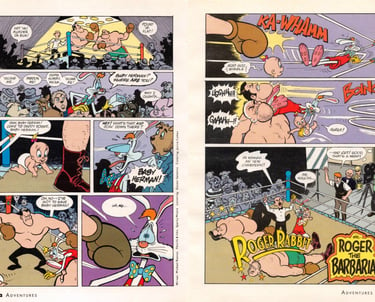

Roger Rabbit's Toontown, a comic book starring the illustrious rabbit, suffered the same issue (pun intended!). Note that, despite being centered around a town of cartoon characters, they're all generic types beyond Roger and his little, inner circle.

Roger Rabbit's Misplaced Legacy: His Displaced Three

Somethin's Cookin' also established the iconic live-action segment finale in which Roger is revealed to be an actor who just so happens to also be a toon. In this world, toons exist freely as sentient beings...although whether actual hand-drawn cartoons also exist is never clearly explained.

Roller Coaster Rabbit

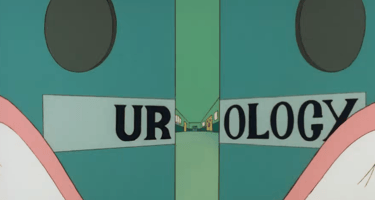

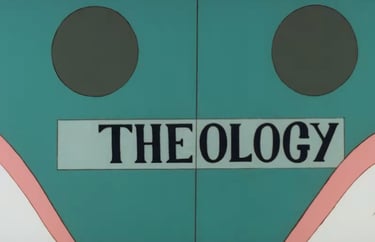

The setup, as expected, is simple enough; Baby Herman swallows a rattle and now Roger must find the cure. Nevertheless, the plot is practically Shakespearean compared to the later Roller Coaster Rabbit and Trail Mix-up which simply have Baby wandering off into trouble without further pretense. Tummy Trouble, comparatively, takes its time to explode. (Note the St. Nowhere joke on the hospital; this is a pop cultural reference to the TV show St. Elsewhere airing around the same time.)

Early on, some of the best gags are in the background. Here, several are made at Mickey Mouse's expense along with a dig at ridiculous hospital costs.

Finally, Roger swallows the rattle himself, jump-starting the action into another gag in which he's rushed through a variety of departments, er, non sequiturs.

Once Roger finally gets to the operating room, the cartoon gains some of Somethins' Cookin' energy. What it never gains, however, is a color palette that matches the variety and vivacity seen in the other three shorts. The walls, doors, even floors all sport a sickly pea-soup color that, although maybe fitting for the setting, isn't particularly appealing.

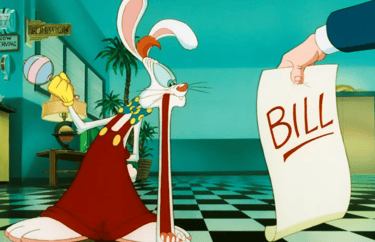

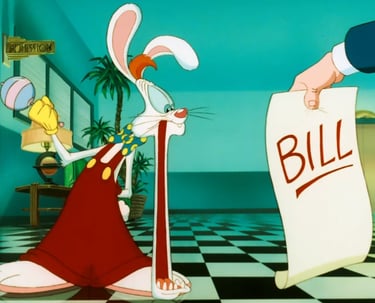

The short ends with clever twist lacking in its three other contemporaries. More than simply concluding on some kind of mishap, here, Roger receives what must be an outrageous bill--another dose of hospital-opportunistic satire. What's more, Baby Herman then proceeds to swallow the rattle again. All in all, a pretty good conclusion.

For better or worse, Tummy Trouble cements the tradition of ending with a live-action bit. This is the only one, incidentally, that actually ends as the director intends, with no Roger-induced fiasco to rear-end the scene.

Tummy Trouble

Oddly, Roller Coaster's opening credits credit Touchstone Pictures, not Disney, for the cartoon's existence. The other two shorts, Tummy Trouble and Trail Mix-up, give the esteem to Disney. Note the Clarabelle Cow "cameo" in the neighboring pic.

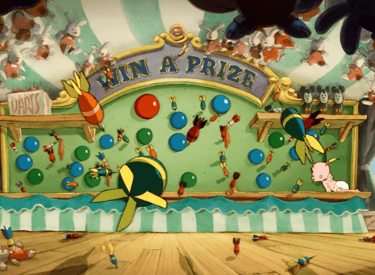

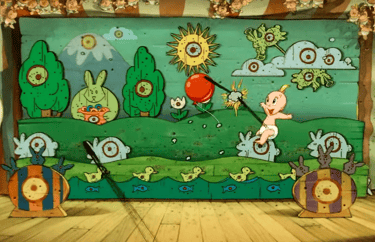

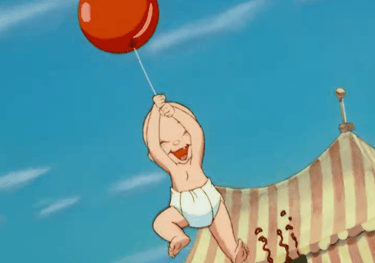

The short's plot is a back-to-basics premise: "Baby's gotten away and needs to be regained." And here, looking for his balloon, Herman crawls obliviously through a dart toss and shooting gallery in what could be seen as a very morbid scene.

Roller Coaster's animators love showing off their smooth use of perspective, often rotating their imaginary camera up, down, and around both baby and bunny. Even the lighting changes and shifts with the movement, granting a great sense of 3-D in what's still a largely 2-D production (the rule for 2-D, generally, is to keep the camera still to save the animators extra work).

This ferris wheel is actually an early example of CGI painted and shaded to resemble the otherwise predominately hand-drawn art. This mix of 2-D and 3-D would become more prominent in upcoming Disney features, including Beauty and the Beast and The Lion King.

Roger's bout with the bull offers some great examples of animated elasticity in action. Freeze-framing is the fan's friend.

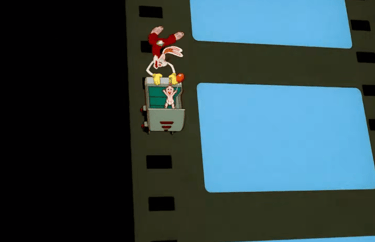

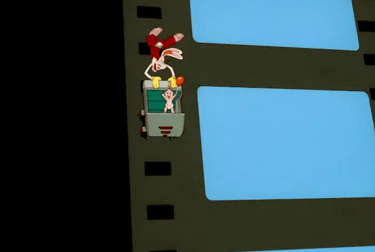

Per its name, the last third of the short sees Roger riding a labyrinthine roller coaster. Apparently, his inadvertent detour onto the reel of film itself was a gag already done in a Popeye cartoon. Nevertheless, the entire sequence is well-done, even if it extends to the point of feeling like filler.

Unlike Tummy Trouble, which at least sports a true ending, Roller Coaster Rabbit doesn't end in the truest sense--it's just interrupted as Roger (apparently) trips up the production's final scene. The gimmick was funny, and fitting, for Somethin's Cookin', but to reuse the gag over and over again afterward (it's used in Trail Mix-up, too) suggests that the writers didn't really know how to otherwise close these cartoons.

Trail Mix-up

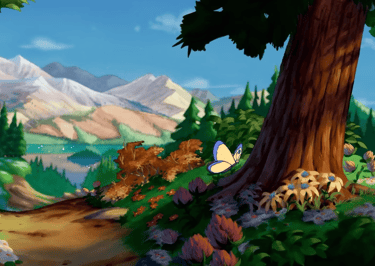

Trail Mix-up's art work is probably the finest of the three shorts--and it's used to funny effect here as the "camera" pans from scenic to anemic.

Jessica was the definition of fan service before the phrase was even invented.

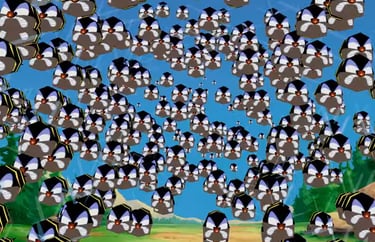

A sequence in which Roger spews some bees makes for several great freeze-frame opportunities. Note the Queen Bee (a nod to Tinker Bell) in the right/bottom shot.

Trail Mix-up expands on the 3-D CG imagery first employed in the previous short. Check out the very low-poly bees from the swarm scene--PS1-level stuff, folks!

The cartoon gets an exhilarating, non-stop second half once Roger and Herman tail a beaver into a Saw Mill. It becomes Splash Mountain, Roger-style.

(Brer?) Bear, Bunny, Beaver, Baby...sounds almost like a game of Rock, Paper, Scissors.

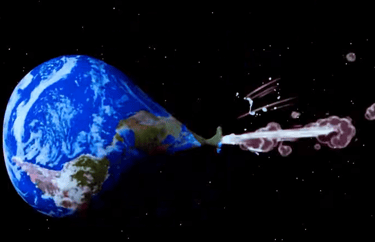

Once again, a live-action sequence is employed to conclude what really wouldn't have a tidy ending otherwise. And this time, it involves Roger ending the world...an almost prophetic, meta signaling of what would happen to the Roger Rabbit franchise--that, tragically, the rabbit would vanish.

Roger's Legacy?

The Rabbit’s legacy is a confounding one. Although celebrated as the preeminent example of paint laid over acetate, its 2-D hand- drawn heritage is what ultimately doomed the hybrid art form’s would-be revival. Computer animation was already on the horizon (even used in the the latter two Roger shorts). And though CGI art boasts its own magic and marvels, it’s still a digital process—opposite, in a sense, to the analogue pencil on paper finesse that gave Roger his birth.

Years later, as Disney experimented with a potential sequel, CGI was the method studio execs wanted. Cheaper and, maybe, more in vogue, even the House of Mouse was happy to relinquish its ink and paint legacy to save a few million simoleons. In brief, the Roger Rabbit sequel never happened because, without that hand-drawn art, there is no heart…no soul.

A CGI Roger is at best a reinvention, at worst a forgery or simulacrum, of the original article. It’s function over form. Functional over exceptional...

And the Rabbit was always about the latter.--D

Roger's legacy? Not much beyond a brief cameo in the 2022 Chip n' Dale: Rescue Rangers film.

Roger’s first cartoon to be released outside his greater motion picture is both the best and worst of his so-called trilogy. While the gimmick is ultimately the same—“I’ll save ya Baby!”—there’s at least something of a greater premise linking the events. Here, it’s a rattle; Baby Herman swallows the toy whole, naturally requiring a freaked-out Roger to hustle the tot toward some emergency care. This means a hospital filled with as many pitfalls and pratfalls as can be humanly mustered.

Compared to Roller Coaster Rabbit and Trail Mix-up, Tummy Trouble is a slower wick to chaos. The first minutes feature a subtler brand of humor with incidental jokes sprinkled throughout the backgrounds as Roger, finally, accidentally swallows the rattle himself. This leads to a would-be surgery sequence that most closely resembles the uninterrupted mania of Somethin’s Cookin’, the initial proof-of-concept vehicle that established the Roger/Baby formula. The lunacy is fun while it lasts, but the gags can’t quite match the unbridled brilliance of its forebear.

What Tummy Trouble does have, beyond some mild satire of America’s inflated healthcare costs, is a true conclusion. In classic cartoon irony, the story ends with Baby Herman cured…only for the tyke to swallow the rattle all over again. It’s poignant in the most perverse of senses, a fitting denouement that doesn’t even require the forced live-action scene that slides in at the end.

Tummy Trouble is, in sum, both the best and worst of Roger’s forgotten three.

Unlike Tummy Trouble, this toon zooms into a fast start. Roger is saddled with the baby, baby loses his balloon and wanders off, and Roger spends the remainder of his eight minutes scrambling after said child. Not particularly clever, but definitely more pandering—more gratuitous—for any attention-challenged audience.

The nihilistic, almost Rube Goldberg machinations of the Somthins’ Cookin’ is still missing here, with Coaster settling for a more contained comedy-of-error fissure over several scenes. In truth, sheer shock value seems to be the key this time, with Baby Herman crawling through both a dart toss and shooting gallery always just a millimeter away from gross, unthinkable tragedy. But, of course, it’s always Roger who gets the punishment.

The finale is a roughly two-minute stretch that justifies the toon’s moniker; Roger and Baby don a roller coaster and careen to almost certain oblivion. It’s a fun and kinetic series of hare-raising thralls and pitfalls that seems more suited for a motion-simulator ride than a theatrical cartoon. Indeed, the problem is a lack of a final punchline—no ending, no final twist of irony or comeuppance or surrender so often associated with the classical short. Rather, the "story" relies on a another contrived live-action sequence in which Roger gets the inexplicable blame for the faux-roller coaster apparently malfunctioning. It makes no sense…but it is a senseless Roger Rabbit cartoon, after all.

On a superficial level, Roller Coaster Rabbit is more enthralling than its immediate predecessor…brighter, more lively, more gratuitous, but with scarcely little hair between those bunny ears.

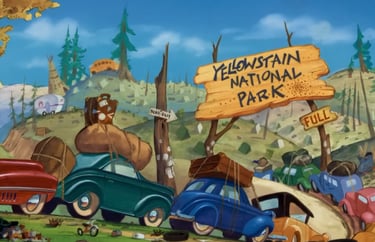

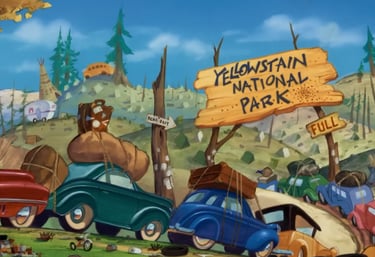

The final Roger Rabbit short sees the bunny dragged to “Yellowstain National Park,” an obvious parody of the famous Yellowstone National Park visited by millions every year. The opening is one of satire, revealing some stately, picturesque landscapes suddenly spoiled (stained) by typical human congestion and pollution. Once again, Roger is left with the baby as “mother dear” sets out for some hunting (which, incidentally, is usually against federal law in any sane reality).

The gags begin simple and obvious, with the obligatory Jessica appearance shuffled to the front before the true chaos begins. The best of these early jokes is a freeze-or-miss-it instance in which Roger is sputtering out a mouthful of bees. Keen-eyed and finger-fast individuals with find plenty of hidden jokes, from bees resembling Mickey Mouse to Tinker Bell.

The real cartoon begins when the beaver shows up—an ambivalent litte creature that eventually leads both bunny and baby through the booby traps of an awesome sawmill. Rendered largely in cleverly disguised CGI, this sequence of scenes is some of the trilogy’s best, pitting Rabbit against blades and cleavers as he chases baby and beaver. The only small flaw is a brief log chute/timber slide sequence that feels cribbed from a bit of Roller Coaster Rabbit.

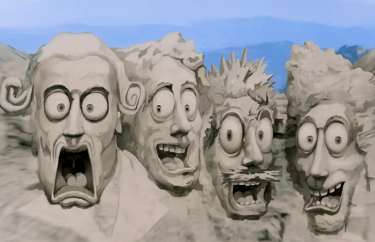

The ending, sadly, repeats the same sin of its precursor, relying on another inexplicable live-action sequence to stitch together a closing. It’s an inspired spectacle, at least, with an actual replica of Mount Rushmore being literally blown to bits just for a fleeting, one-note gag. But the conclusion feels unearned, more desperate than genuine, slamming the proverbial gate down on a more organic finale. If a second trilogy of Roger Rabbit shorts been conducted, hopefully this cliche of mixing an angry, live-action “director” with a befuddled bunny would have, at last, been abandoned.

Bunny Bits: Did You Know...?

Bunny Bits: Did You Know...?

Bunny Bits: Did You Know...?

Unlike its successors, Tummy Trouble is purely a hand-drawn spectacle. No early CGI here! It also received an unnecessary graphic novel adaptation.

As of November 2025, Disney's rights to the Roger Rabbit character has reverted back to author Gary K. Wolf. This allows him to create new Roger-related projects independent of Disney, although the company still holds control of the original film, assets, character designs specific thereof, and the derivative media it spawned.

Bunny Bits: Did You Know...?

The faux Mt. Rushmore used here was a real handcrafted model created just to be destroyed for this throwaway ending scene.

One long-standing rule in animation is to NEVER MOVE THE CAMERA. The reason is simple: it's a lot harder to animate a character when the perspective and angles are constantly shifting. Nevertheless, the camera is moved with rebellious aplomb in these Roger shorts, providing a much more dynamic experience few viewers will likely acknowledge, let alone appreciate.

Bunny Bits: Did You Know...?

Unbeknownst to most, Roger Rabbit did receive a sequel...albeit in graphic novel form. Titled Roger Rabbit in the Resurrection of Doom, it came and went without much notice.

Contact: lostnostalgiaproductions@gmail.com

Website: www.lostnostalgia.com

Like what we're doing? Please consider throwing us a dollar into our Patreon page's tip jar!