Star Wars: The Thrawn Trilogy - Review

Heir to the Empire, Dark Force Rising, and The Last Command

More than blockbuster or cinematic revolution, Star Wars was a cultural touchstone—a grateful gateway of escape for cynical Gen X’ers growing up in a morally-deluded, nebulous America. The 1977 film was a revelation, reminding those immune to the platitudes preached by their rote childhood churches that everyone has a destiny, good always triumphs in the end, and even the worse can be redeemed. That was the essence of the Star Wars story, its spirit and legacy. And as simple, even insipid, as those maxims might seem, it was like manna for those seeking some kernel of meaning, those looking for “spirituality” without the strings and stings of religiosity. Those wanting Faith’s feel-good highs without the rules and guilty trips.

One wonders, had mastermind George Lucas been so inclined, what Star Wars could have become after the original trilogy concluded in 1983. Already a modern myth and a borderline religion for some, the saga might have propelled Lucas to the heights of a modern-day Joseph Smith or L. Ron Hubbard, making him king of a very different kind of media empire. One that transcended mere fandom for a greater fanaticism, one that brought the moviegoer back to church…or rather, turned the movie into the “church.” Forget Pat Robertson or Joel Osteen. George Lucas could have been the greatest televangelist of all, redefining the entire form.

But Lucas didn’t do that. Rather, he did nothing at all, letting the Star Wars franchise stagnate for the rest of the decade. Outside a few cartoons, comics, and low-budget Ewok schlock, that original trilogy was all that followers got.

Until Timothy Zahn. After years of encroaching heat death, Star Wars found itself a new prophet, a man tasked with essentially devising the saga’s next storyline, episodes 7, 8, and 9. The challenge was not inconsiderable. How does one take a fairy tale with a definitive finale and continue it anyway, respecting its traditions while pioneering something new? Two decades later, Disney would attempt this very deed with its own sequel trilogy, undermining the entire franchise with the grace of a drunken Gungan. But Zahn, as if wielding the Force himself, managed to devise a trilogy--Heir to the Empire, Dark Force Rising, and The Last Command--worthy of George Lucas.

Later coined “The Thrawn Trilogy,” Zahn jumps the proceedings five years ahead to a New Republic caught between internal political divisions and a vengeful, if diminished, Empire prowling from the galactic fringes. Likewise, the heroes have their own struggles. Leia and Han are married but, due to their erratic roles and duties, are often kept worlds apart. The former is struggling to learn the Force, the latter how to be a good husband and father while still serving the Republic he risked so much to restore. Luke’s no better, a man uncertain about his role in the universe. Whether the last Jedi or the first of a new generation, he’s unclear how to best impart his fragmented knowledge, let alone restart the entire Order. Overall, it’s a perfectly believable beginning. But then Zahn does the impossible.

He introduces Thrawn.

Darth Vader might be the ultimate villain, but Grand Admiral Thrawn is a captivating fright in his own right; despite being a red-eyed, reptilian alien, he’s lightyears more dynamic and dangerously charismatic than his former bosses. Darth is an over-glorified henchman, after all. And the Emperor is simply evil for the sake of being evil. Thrawn, rather, is more nuanced, playing neither the stalking shadow nor cackling villain, but rather the soldier devoted to his mission’s leading conviction: the galaxy is a messy, amoral place that demands control. While Vader and his Emperor adhere to their cryptic mysticism, Thrawn acts on sheer, calculated reason.

Zahn doesn’t stop with Thrawn, however. He also introduces the lethal Mara Jade, a strong woman long before the likes of a Rey or an Ahsoka. Jade hates Luke. Desperately, seethingly, she seeks—even needs—to kill him. It’s this unbridled, seemingly senseless hatred, in fact, that makes her so fascinating…yet innately unlikable, making her the ultimate anti-villain. She’ll later gain a sympathetic edge, becoming respected, even loved, in the later lore. Until Disney, that is, excised her from existence.

If Zahn’s saga bears a shortcoming, it could be the distinct lack of whimsy that so characterized the original stories. Lucas’ vision was more fantasy than science fiction, more Zen Spiritualism than Stephen Hawking. But Zahn leans toward the latter, providing a story more grounded than its source inspirations. Plenty of action, wry remarks, and crazy escapes still punctuate the unfolding drama, but nothing quite matching a village of jabbering bears or a fight within a giant gangster worm’s desert lair. Zahn even demystifies the Force a bit, creating an animal (the ysalamiri) that can repel or otherwise neutralize that ethereal energy, essentially depowering any nearby Force-user. It’s really a contrivance, of course—a convenient Kryptonite to use against an overpowered Luke--but it also suggests (inadvertently or not) that the Force is less a spiritual power and more like a physical law or phenomenon, such as gravity or magnetism. Long before George Lucas made The Force “scientific” by introducing midi-chlorians, Zahn had already done the same…just in a different way.

But Zahn is faithful where it counts; Luke, Leia, Han, Threepio, Artoo, Wedge…they’re all represented here exactly as fans would expect—faithfully, accurately, and with considerable attention. It’s the characters, after all, that make the tales so endlessly endearing. While Disney would later error, fundamentally changing the classic cast in ways that didn’t make sense, Zahn interpreted them rightly, even righteously, inscribing them properly to the page.

George Lucas always seemed indifferent to Zahn’s achievement, his following prequel trilogy taking a very different tone and approach. Similarly, the scripts for his own 7, 8, and 9 sequel series are said to differ drastically from Zahn’s original vision, although whether they would have replaced his timeline or simply ignored it with a time-skip it is not entirely clear.

Not that it matters. Though Zahn’s work is now considered noncanonical, the epic always seemed to fall short of complete, official acceptance. It was “canonical,” yet felt vaguely hypothetical all the same. Like Schrodinger’s Cat, it was a storyline both living and dead.

Sadly, in a post-Lucas world where an interloping corporation now makes the decisions, Zahn’s work is at best a relic of a different era, an apocryphal gospel long discarded by the current clergy. The Thrawn Trilogy is what Stars Wars both was and should have become. Now it’s just gone. And the losers, really, aren’t Disney, Lucas, or even Timothy Zahn.

It’s the fans. The adherents to a once glorious but now fading Faith. Perhaps a Chosen One will one day descend to restore the former Order. But until then…

…Zahn’s tomes are still a fascinating--if haunting--jaunt into an alternate, would-be time. - D

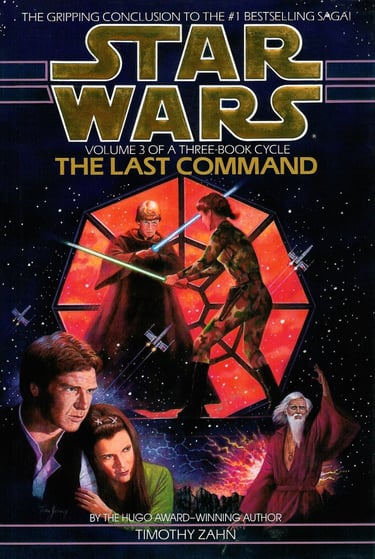

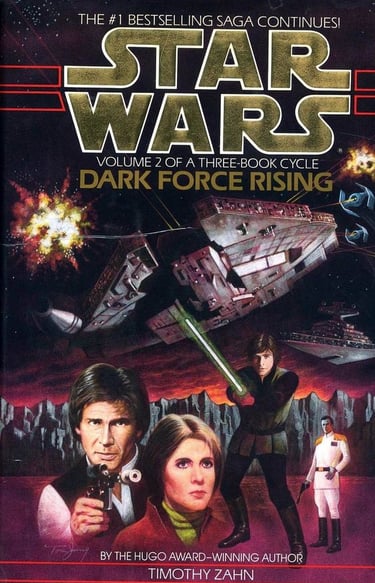

The original books circa the early '90s. For the time, these were episodes 7, 8, and 9. Something like The Force Awakens would have been unthinkable.

The audiobook version, read (and acted) by Marc Thompson, is excellent. It's more radio drama than anything.

Heir to the Empire after the "Legends" rebranding. It's an ignoble end for what began as a glorious beginning.

Contact: lostnostalgiaproductions@gmail.com

Website: www.lostnostalgia.com

Like what we're doing? Please consider throwing us a dollar into our Patreon page's tip jar!