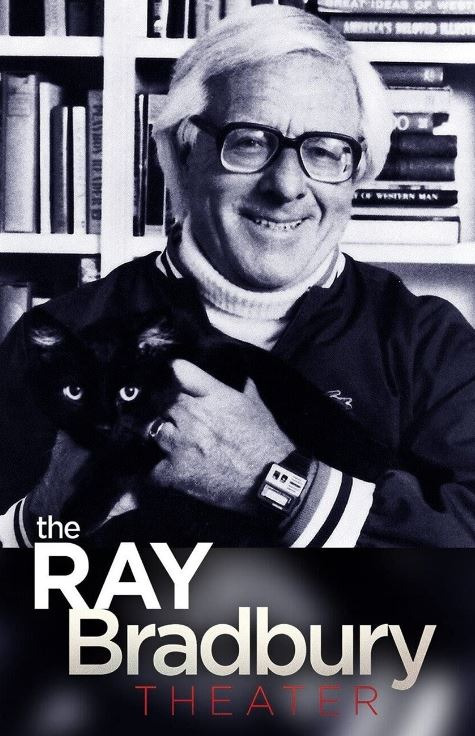

Ray Bradbury Theater in Review

Originally published in the May 1943 edition of Weird Tales (a pulpy periodical that specialized in stories of the strange and fantastic), Bradbury's The Crowd is a story built on supernatural paranoia-if a malicious but inconspicuous force of (perhaps) ghostly origin wanted someone dead, what could that person do? Who would believe him? Where would he go? Is the danger even real or just the mad specter of his imagination?

The TV adaptation keeps to this general theme; Joe suffers a car crash in the middle of the night, finding himself surrounded by a vaguely ghoulish crowd of onlookers. He's flooded by a cacophony of strange voices, some seemingly helpful, some potentially dangerous. Voices saying things like: He needs air. Should we move him? Call an ambulance. He survives the ordeal but is left haunted by the inexplicability of it all. Why were there so many spectators on hand at 2:00 in the morning? How did they gather so fast? Were they trying to help, or hinder, his survival?

Joe's doubts are further honed when an accident occurs outside his apartment just a few days later. Within seconds, people begin filling the scene, engulfing the comatose body (the episode's victims are always conveniently outside their vehicles). He runs outside to investigate the matter himself, finding the person already dead and the droves of onlookers especially eerie...and familiar.

Convinced something sinister is afoot, Joe begins searching old press footage of other local accidents and makes a disturbing discovery--the same faces are present at every scene. A young boy. A red-haired woman. An old man. A dude in a raincoat. And a mysterious figure whose face is always obscured. On a hunch, Joe checks the records of the nearby morgue and draws an unthinkable conclusion; these voyeurs are not people at all, but the ghosts of them...victims of similar car accidents. Now they wait, apparently, for more wrecks, anxious to reap another soul for their grimly throngs. Wanting answers, Joe decides to contact these dubious beings. Tragedy ensues.

It's a provocative yarn, a ghost story enhanced by some somber visuals and powerfully understated performances. Moreover, it's a tantalizing mystery, one that will keep viewers entranced and guessing until the bitter denouement--a twist ending that, if a little contrived, still evokes a subtle horror.

But it's the mystery more than the morbidity that will keep most viewers glued, and here, the story falters, offering few if any insights into the "ghosts" and their true purpose. Joe's confrontation with them reveals little of significance, and the secret behind the unidentifiable stranger is never explained nor receives a proper payoff. The episode is an enigma without an answer--or worse, a purpose--beyond instilling a vague sense of unease.

The real question, however, is whether fans of the short story will approve of this updated version. In the original, the reader is left with the dim possibility that it's Joe (Mr. Spallner), not the world, that's gone crazy. That there is no supernatural street-side conspiracy to grab accident-prone souls; rather, it's all a paranoid delusion inside Joe's head. But the TV rendition changes the pitch, showing undeniably that its accident chasers are indeed ghosts, or at least something otherworldly, always waiting, always watching.

Except, despite Joe's tentative speculations, these beings are never actually shown moving the bodies or stealing the victims' air or otherwise bringing the deaths he suspects...and this, perhaps, is the real shift in the mystery. Joe sees villainy where, perhaps, the ghostly crowd's true intent is very different. No outright hostility is ever clearly shown, just inferred. Perhaps they're not good or evil necessarily, just blue-collar spirits fulfilling their roles, collecting the next souls ripe for a purgatorial penance.

Unfortunately, due to a plot that doesn't care, the episode ends on these inconclusive notes, leaving mysteries on top of mysteries. The story remains a good mind-bender, but those wanting more substance will likely find the proceedings, well, a little soulless.--D

First published in Startling Stories and later collected in Bradbury’s The Illustrated Man anthology, the original story splits itself cleverly between two men, a Mr. Smith and a Mr. Braling, who have both grown weary of their indomitable wives. For Smith’s part, he feels smothered his wife’s incessant affection. For Braling, his marriage was one born of an infatuated woman’s blackmail, not one of true romance. Both are portrayed somewhat sympathetically. And both receive rather bitter (if inverted) endings.

The duality is mostly dropped, however, for this retelling, with Mr. Braling becoming a near-composite of the original characters. Now less sympathetic (and less justified), it’s not a loveless marriage the man now resents, but rather that his wife loves him too much—Mr. Smith’s problem from the original telling. Long resigned to her constant, doting control, Braling receives unexpected assistance from the mysterious Marionette, Inc., a shadowy enterprise that specializes in the design of artificial humans. Fantoccini, the company’s face and representative, shows him one of these unnerving creations—a perfect Braling-duplicate that can act and behave with his exact mannerisms. And it’s exactly what the uptight husband needs, or so he thinks. Let the robot-whatsit play house with the wife while he, the genuine human, plays in the city, free and unfettered.

Although Mr. Smith does eventually make an appearance with a very slight, B-story of his own, this is really Braling’s tale from start to similar finish. But while the original had Braling’s double complaining about being locked away constantly, being taken for granted, and that he'd fallen for his wife, this version focuses solely, and probably smartly, on just the latter. As “Braling 1” enjoyed spending time away from his wife, “Braling 2” was happily spending that same time with her, the recipient of a woman's grateful love. In the end, there's only room for one husband, and this brings a brutal reckoning between the two.

Even for a short story, Marionette, Inc. was a short, almost frivolous read; a slightly tragic distraction born of a kind of morbid paranoia. The TV script had no choice but to administer some filler, fleshing out Braling’s world with necessary but also needless detail; it now reveals a seedy reality in which invisible corporations can spy into the lives of potential clients, divining their wishes and promising devilish tech. But ultimately, the added details only provide time to recognize premise's obvious flaws. What if one of these androids breaks down? How will one of these fakes behave should a spouse uncover its true nature? What if word of these doppelgangers becomes too widespread amongst the public at large? Do these doppelgangers also contain the necessary memories of their masters? If so, how…? And what happens if one of these things commits a crime…or worse?

The initial short story, by virtue of its length, could conclude its little yarn before serious consideration developed. But a 23-minute episode grants the viewer too much time in which to pick out the plot’s absurdities and formulate some very obvious questions—questions Mr. Braling should have been astute enough to ask himself.

Like, what if something goes wrong?

Yes, Mr. Braling. Yes indeed.--D

Many of Bradbury’s works are psychological in nature. Or, at least, they presume to be. The Playground, in particular, takes a man’s childhood sufferings and then mixes it with cheap, contemporary thrills. Creepy kids. Perpetual twilight. Gnashing fangs, howls, and wolfish mobs. Are these terrors real, or the imaginings of a damaged man?

And that man, for this tale, is Charles, a soul still haunted by a childhood fraught with trauma. His school-age peers, led by an older brat named Ralph, would chase him to the local playground each day, bullying him into submission. Why these gangs of children so hated this specific six-year-old is never explained. Kids are just mean—and scary—apparently.

Now, many years later, Charles is a widow whose son Steve desperately wants to go to the playground. The same playground which just so happens to be across the street from their house. How the kid never managed a trip there before is also conveniently ignored.

But Charles, remembering the brutal treatment he got in the age-old place, is reluctant to take his son. He’d rather shelter the boy from the cruelty waiting there or, even better, take the abuse instead. Some might wonder, of course, why Charles is so certain Steve will receive the same bullying he got 65 years earlier. These aren’t the same kids, after all.

Then again, maybe one is.

Scoping out the playground for himself, Charles begins seeing the specter of Ralph, the ringleader and mastermind behind all his childhood sufferings. The bully seems to want him back to absorb more of his smirking torture. The why, however, is again unclear. Is Ralph dead? Is this his ghost? Or is this all the manifestation of a man’s past trauma and misery? As in the similarly esoteric The Crowd, the questions keep coming, but never the answers.

The ending is no better, contriving an inexplicable switcheroo in which Charles and Steve swap minds, the former now able take the abuse meant for his son. It doesn’t make a bit of sense, but does leave the viewer with some interpretations to ponder:

1. Charles is now the “son,” able to take the abuse Steve would have endured otherwise. The boy’s innocence is now preserved.

2. The two only swap in a figurative or psychological sense. Steve, sensing his father’s fears, decides to take the mature role, willingly subjecting himself to the playground abuse as a sort of proxy for his father. A vicarious, cathartic release (or passing of the torch) for Dad, so to speak, allowing the damaged man to finally regain his childhood serenity.

3. Steve is actually on the kids’ side, happily offering up his father so he can have full access to the playground. Indeed, he seems to be the impetus for the switch, and does nothing to help poor Dad as the kids attack him (inexplicably) thereafter.

More interpretations are doubtlessly possible, for that’s the advantage of nonsense—who can deduce truth from random mishmash? What’s the answer to A+B+X+Y when the variables are never defined? One, indeed, can only guess…if he even bothers to try.

Watch The Playground for its haunting ambiance and nightmarish attractions. But please, don’t watch it for the plot.--D

Banshee recalls the ghost stories of old. The kind shared over a campfire in which the details are scarce—it’s all build up and unnerving scare. A narration told in a slow, deliberate voice meant to instill a foreboding chill in those soon destined for bed. For better or worse, this story follows the same tradition.

The episode opens on a cab driving down a lonely road as lyrical music plays in the background. It’s an oddly upbeat beginning to a tale of ghostly foreboding—Doug, a talented horror novelist and screenwriter, is traveling the empty lands of Ireland where a famed director awaits. There, he’ll deliver his latest work, a screenplay from which the director hopes to film his latest masterpiece. Unfortunately, the cabbie warns, the man is not an easy character to work with.

And this soon proves true. Most of the episode is spent on John, the director, both praising and berating Doug’s talents. He pretends not to like his script, then—haha—he does like it! He recites a negative review regarding Doug’s body of work, then—haha—admits he made the whole thing up! He pretends to hear a banshee moaning outside in the woods, then—haha—goads Doug into going out to investigate! By this time, Doug is tiring of the man’s arrogant shenanigans. But reluctantly, he agrees.

So outside he goes. And lo, he spots a mysterious woman wafting through the trees, clad in a ghostly wedding dress. He suspects another prank, but soon begins thinking otherwise as she, in her soulful way, begins lamenting the tireless, timeless love she holds for the distinguished director (and apparent womanizer). As Doug returns to the house, she begs him to draw John out.

Fittingly spooked, Doug tells John of the experience. The director deems it a game—a fair squaring of the ledgers—and is good enough to play along. What happens once he steps outside, though, remains a secret only Bradbury knows.

There’s no plot here. It’s all premise and belabored banter between characters that barely matter. But the crunched, fire-lit quarters evoke a fine sense of unease, and the acting is slavishly overwrought, adding ominous “fun” to what’s a decidedly unlikely scenario…banshee or not. It’s a story that draws on too long but still serves its purpose, offering an atmosphere that evokes, maybe, a tiny chill. Or, at least, a little giggle.

And like most ghost stories—and most ghosts—it’s utterly vapid beyond the clinching denouement. Once the tale is told, once the ghost is seen, it loses its only purpose.--D

Closing this Bradbury sampling is The Screaming Woman—which, if anything, proves how a touch of creepy music can transform an otherwise mundane story into something almost scary.

So, much to her parents’ chagrin, Heather loves scary stories! While most young girls might cuddle up in bed with a book of fairy tales or a Judy Blume novel, this girl sleeps with a copy of Tales from the Crypt under her pillow. She’s definitely one of a kind.

But this predilection for the weird brings certain ramifications when, while skulking about outside, Heather hears a woman screaming from a nearby wood. She follows the moans to a patch of soft dirt and deduces the horrible truth…someone is buried there, alive. She runs to get help but, due to her obsession with everything morbid, no one takes her seriously. It’s not unlike the old “Boy Who Cried Wolf” fable, except here, Heather’s only crime is having an inordinate passion for pulpy stories. The true sin, perhaps, belongs to those who don’t believe her.

The Screaming Woman is, if anything, ironic—for a tale that so brazenly references the schlocky comics and scandalous pages of ages past, this is a decidedly tame and borderline insipid story, what with its sunny suburban sprawls and incidental villains. Even Heather, played by a young Drew Barrymore, seems more amused than mortified by her unfolding drama; with no one willing to help her, she sets out to save the woman on her own, blocked each time by a convenient or nonsensical contrivance. It’s a mystery that’s essentially empty, for despite knowing the woman is buried alive…she spends more time sleuthing out the lady’s persecutor than simply trying to dig her up.

The real fear, if there is any, comes less from the flimsy script and more from the ominous (if generic) score that plays in almost every scene. It grants even the sunniest scenes an unsettling feeling despite the absence of anything even remotely threatening. It’s a staple of the series, of course, to use such a musical crutch to infuse its often hollow episodes with a semblance of suspense. It’s artificial flavoring smeared atop day-old toast, or better, an inverted laugh track trying to evoke a ghost not really there.

And such is The Screaming Woman, a rather pedestrian tale that, at least, does follow the basic rules of plot and storytelling. Backhanded praise indeed, but still more than what its sister shows often bother to offer.--D

Judging from this sampling, many would deem The Ray Bradbury Theater as a mediocre effort, and that’s probably an accurate assessment. It’s the sort of show one catches at 2am when the brain is already half asleep. Against these logic-impaired circumstances, the show succeeds.

But more intrepid souls should just seek the books, particularly The Illustrated Man, The Martian Chronicles, and Fahrenheit 451. A low-budget TV show just can’t hope to do these imaginative tales justice.

Print, sometimes, is the greatest canvas.