YoYo's Puzzle Park

YoYo's Puzzle Park Review

Platform: PlayStation

The single-screen platformer has had, roughly, three epochs of development. What started with Donkey Kong, a “get-to-the-top” experience, eventually evolved (or side-stepped) into Bubble Bobble, a game which emphasized battle and enemy elimination. This twist in mechanics set the new paradigm, inspiring a bevy of excellent, if vaguely similar, games to follow. Snow Bros. Rod-Land. Zupapa. And more recently, Super Mutant Alien Assault and Dwarf Journey. But that suggests only two evolutions…

The truth is that the third paradigm shift never fully took form; as if sabotaged, the SSP took a tragic fall from grace in the latter ‘90s from which it never recovered. Legions of crummy, low-effort titles were spat into the market, diluting a genre that was already searching for relevancy. Even quality titles, like Nightmare in the Dark and the aforementioned Zupapa!, chose to uphold the same decades-baked tropes and strokes versus attempting anything truly innovative.

Except one game, that is…one of audacious, seminal design that somehow missed a North American release. A game that proved to not only be a phenomenal single-screen platformer, but just a terrific platformer, period. A game which brims with more personality that even the Crash Bandicoots and Spyros of its era. A game that came from, of all things, a developer more associated with the space shooter than the bop n’ jump.

That company is Irem. And the game is YoYo’s Puzzle Park, or Gussun’s Paradise as it was known in Japan. It served as the quirky, if contradictory, finale to Gussun Oyoyo, a very puzzle-centric series of games in which the player must lead the lemming-like Gussun (or his twin bro Oyoyo) to an exit by guiding falling blocks. Fun but extremely challenging, the various titles offered a wacky alternate take on Tetris that only a Japanese developer would dare devise.

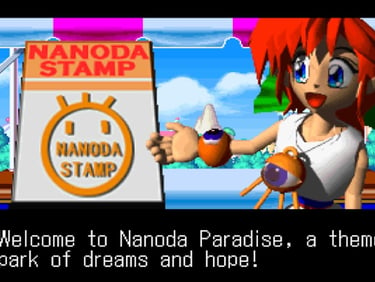

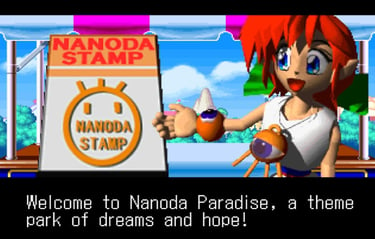

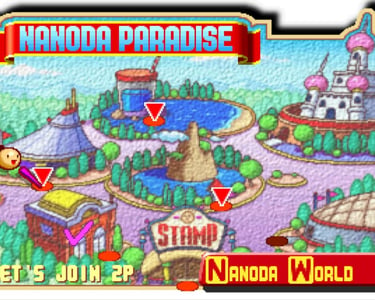

But YoYo’s Puzzle Park, despite what its title implies, sheds the brain-busting trappings of its predecessors for a more action-packed experience. Players now directly control the brothers in what can be a solo or cooperative experience—upon visiting Nanoda Paradise, an amusement park “full of thrilling and exciting attractions,” the duo (and accompanying galpal Emily) are beset by the villainous YoYo, a squat alien-like thing backed by an armada of similar squishy creatures. For whatever reason, these green fiends want the park for themselves, and only the twins—armed with party poppers of all things—can foil their plans.

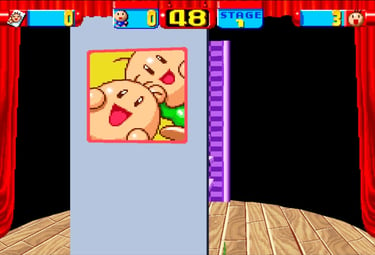

Yes, popping an alien or other baddie leaves them temporarily stunned and now vulnerable to being knocked or tossed into a stage’s many constantly spawning, sentient bombs. These explosives can also be thrown, making the objective simple and plenty addictive—by herding bombs and baddies closer together, a mega explosion can be wrought, incinerating multiple (and hopefully all) the enemies at once for outlandish point bonuses. This process of stunning, bumping, and lumping is clumsy at first blush, but once mastered, screens can often be cleaned within seconds.

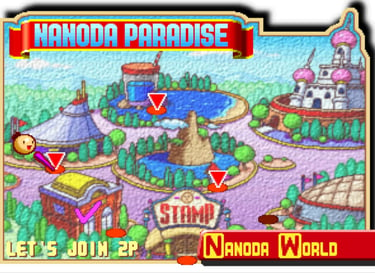

But what makes YoYo so memorable is really the presentation, its sense of humor, the way every enemy squirms with perky urgency and the way each of the park’s locations vibrate with their own zest and style. Nanoda Paradise is a Disneyland subverted, its cheery mascots replaced by the rascally, anarchic gremlins of Looney Tunes fame, its realms more topsy-turvy than a trippy trip into Wonderland, its challenges madder than a wacked-out Japanese game show. Each of the park’s locations sport their own themes and gimmicks, from a motion simulator ride that tips and dips the screen like a see-sawing shadow box to a jungle boat cruise of platforms shifting and swaying as if rolling on a tide. Six of these faux, exotic worlds (with ten stages apiece) await to be scorched clean of their alien invaders, upon which an airship—one of the game’s two climactic bosses—becomes selectable for a final reckoning. It’s all fast, colorful, and shockingly ingenious.

The powerups are also delightfully unique; a duck-faced inner tube allows the brothers to flap around the screen, an underarm robotic firearm shoots piercing lasers across the arena, a flying saucer grants the ability to “thrust” repeatedly in midair, and a special soda pop grants (in more predictable fashion) a nice boost in movement speed. Likewise, score-multiplier cards are dropped as foes are felled, with the higher-value items gained after successful, multi-chained attacks.

Graphically, the game is an artful fusion of effusive, beautiful sprites and striking 3-D backdrops. The audio is similarly inspired--ghostly echoes and vague notions of the Jaws-theme enhance the game’s “Seaworld” locale, while conversely, an understated composition of clicks, clacks, and dings ring throughout the “VR” stages. Gussun and Oyoyo further the fervor with their own yips and cries and frantic antics; there’s no aspect, feature, or creature in Puzzle Park that isn’t drenched in anarchic (but endearing) spirit.

If the game has a failing, it’s the opening/ending cinematics, which seem woefully chintzy compared to the posh and polished fun residing just beyond. The inability to drop through platforms is perhaps another slight misstep. But these niggles are but the superfluous flotsam riding the tide of an overall excellent, even brilliant experience.

The single-screen platformer was born in the arcade but died in the home; YoYo’s Puzzle Park served as both the genre’s highest pinnacle and untimely grave, foretelling a third paradigm that never quite came. The beginnings of a revolution no one noticed. A swan song more than the genre's second chance.

Like a phoenix unable to resurrect itself, YoYo came like a farewell parade, a glorious celebration that then turned a corner and got lost, never to be seen again. But for those who caught that one glorious performance, it wasn’t just spectacle they got, but a vision. A proof-of-concept nobody wanted. A paradigm realized, then swiftly retired.--D

Publisher: JVC Digital Studios (PAL)

Developer: Irem Software Engineering

Release: 1999

Genre: Single-screen Platformer

The game provides three weird vehicles that serve as powerups. Here, Gussun goes "Duck Duck and Away" with his flappy bird.

Gussun and Oyoyo find the famed theme park, Nanoda Paradise, invaded by green meanies. It's unforgivable!

Being a theme park, each of Nanoda's locations are based on, well, a theme. Shown above is the game's version of Disney's Jungle Cruise.

The different locales all provide unique, curious challenges. For example, in Nanoda World (top), the screen tilts in conjunction with the simulator ride showing in the back. (Which is rendered in full looping 3-D!) The bottom pic, Nanoda Musical, is set on a soundstage that literally spins at specific intervals as the action proceeds.

YoYo's Puzzle Park is split across six main lands, the first five of which can be selected in any order--just like real life!

Contact: lostnostalgiaproductions@gmail.com

Website: www.lostnostalgia.com

Like what we're doing? Please consider throwing us a dollar into our Patreon page's tip jar!