Freaky Friday 1976: Ellen's Elegance Versus Annabel's Angst

Kids often wish to be “big”; they want to drive, they want to drink, they want the freedom that being an adult automatically entails. But how many teens wish to be their parents? And more accurately, how many daughters dream of becoming their mothers?

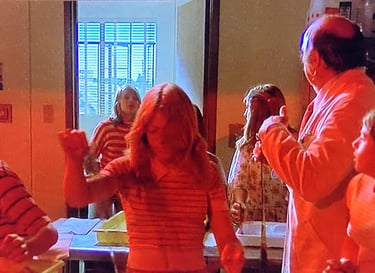

Such is the premise of Freaky Friday, the weird but enduring tale of an awkward teen, Annabel Andrews, swapping bodies with Ellen, her elegant mother. And indeed, the daughter does freak out, but not for the reasons one might assume. Annabel is certainly shocked at finding herself in Mom’s much more developed form. But rather than curse the Fates for ruining her life, she celebrates. She dances around the house, rockin’ a housewife’s life in Mom’s lithe, idyllic skin…all while Ellen is relegated to surviving a school day as the frumpy, grumpy teen. Both will learn that, whether child or adult, student or homemaker, life can be tough, complicated…even a little cruel.

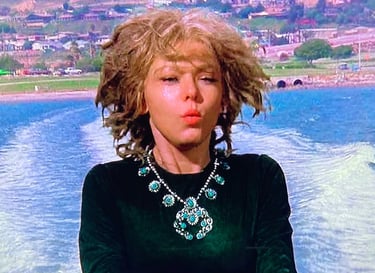

Released in 1976, one might wonder some fifty years later how “realistic” the movie is in developing its premise. Would the average girl enjoy a switcheroo with her “uncool” Mom? The answer would, presumably, be a resounding “no,” but Freaky’s Annabel here is no average girl. More boy, in fact, at first introduction, with her tacky clothes and unkempt hair and a penchant for riding skateboards and eating chocolate sundaes at breakfast. She hates her little brother, deeming him too neat, too cute, too obedient and tidy; she plays a mean game of field hockey; she is somewhat of a slob. In short, she’s the extreme opposite of her refined, comely mother, but the differences are so stark—so exaggerated—they render Annabel borderline unlikable.

The “switch event” is also peculiar; unlike later films where some kind of magic totem or MacGuffin is usually employed, the two stars here simply wish to be their counterpart for the day and—whoosh—they’re literally placed in the other’s shoes. Ellen, now the daughter, then proceeds to make a fool of herself at school, committing a number of snafus and social faux paus before horrifically botching a pivotal hockey match. Of course, none of these failures necessarily proves that teenage Annabel’s life is excessively difficult—just difficult for someone suddenly forced to learn an entirely new life without a lick of guidance. Why Ellen even participates in the charade and doesn’t simply invent an excuse to come home is chalked up to simple pride, if vaguely. (Editor’s Note: In the book version, Ellen does indeed play “hooky,” wisely avoiding school altogether.)

Unlike Mom, Annabel is overjoyed with the switch, now able to live the “high life” as a pretty housewife. Everything seems great until she overloads the washing machine, fights with the housekeeper, can’t find the checkbook to pay the delivery man, and is suddenly saddled with cooking for her father’s elaborate dinner party. More than once, Annabel even calls good ol’ Dad a chauvinist. But fair or not, most of her mishaps are simply the products of inexperience…not from a crushing workload or list of brutal responsibilities.

Nevertheless, Annabel still finds time to have fun in a way her “younger” mother never does; she flirts with the boy she likes from across the street, plays baseball with her brother, and somehow flits into a new outfit every couple of scenes. Kudos go to actress Barbara Harris who deftly melds the winsome teen and put-upon mom into a seamless whole. In mommy’s body, Annabel finally finds her femininity, her playfulness, her purpose…while still complaining and smacking gum like a typical teen. Neither Ellen nor Annabel make a huge impression by themselves, but once combined, the Annabel/Ellen amalgam packs a certain (uncomfortable) allure.

But switcheroo films sink or succeed by the talents of their casts; can the two actors play each other’s characters convincingly? Can the audience be convinced that the mom is really the daughter, and vice versa? It’s a problem even Freaky Friday's esteemed actors can’t quite dodge. Jodie Foster’s Annabel is so self-serious--so quasi-mature--she doesn’t “feel” different enough once the swap occurs; now playing “Mom,” she really just feels like a slightly more stuffy, well-spoken version of herself. Barbara Harris fares better, accurately portraying a stereotypical, daydreaming daughter…just not the specifically jaded, humorless Annabel. It’s hard to imagine Annabel, as portrayed early on, ever dancing spritely in the mirror or trying on cute outfits. But once granted Mommy’s svelte form, she becomes the typical teen—an eager, flirtatious giggler given to fashion and shy, silly smiles. Maybe becoming Mommy really is that intoxicating, but the script would have benefited from portraying Annabel more like a typical thirteen-year-old girl. Foster's Annabel is just too cynical, too tired, too boyish…to sync with Harris’ more effervescent, girly performance.

The movie is also incredibly wacky, especially in its final arc that involves a ridiculous car chase and the two heroines switching back not in mind, but in body, meaning that the individuals physically teleport to the other’s location. This leaves Mom, now back in her own body, still water skiing and performing tricks, while Annabel, herself again, still driving with a squad of police cars careening after her. It all concludes on an inexplicably happy note, of course, like a cartoon or video game that doesn’t care much for consequence. It’s all about the gags and the thrill, not the havoc left behind.

Freaky Friday is a flawed story, but the premise itself continues to compel. A half-century later, the so-called “switcheroo” or “body swap” has become a genre unto itself, a sort of wish-fulfilling fantasy that usually ends in a sobering but reassuring “be careful what you wish for” conclusion. Movies like Big and 13 Going on to 30 bend the equation with varied results, while films like Switch take an outright more subversive turn.

And Freaky Friday has itself spawned a number of remakes and off-shoots, most notably a 1995 reboot starring Shelley Long, a 2003 redo with Lindsay Lohan, and a 2018 version that adapts the story as a bizarre musical. But the unsung hero, perhaps, is Mary Rodgers, who wrote the original 1972 novel from which everything else spawned. Or rather, the grandfather of the genre, F. Anstey, who wrote a similar tale back in 1882 featuring a Dad/Son reversal.

Why the genre lives on is a debate for a different day, but there’s always something fixating, relatable, and fun about a fish-out-of-water story. Or soul-out-of-body, as the case may be. It just seems that, in Freaky’s case, it’s an unfair trade. Indeed, countless people dream of being young again. But how many folks, especially teens, wish to be so old?--D

On an offhanded, simultaneous "wish," Annabel and Ellen swap bodies, then switch back later at the most inopportune time. Of all the Freaky films, the original is the most slapstick happy.

This is Annabel as portrayed at the beginning. Not particularly likable or attractive, calling her a "tomboy" would be generous. Maybe a switch with Dad would have been more fitting?

Mom is everything Annabel is not; elegant, dignified, and more importantly, feminine. She's her daughter's stark opposite; so much so, it strains credibility.

Now "Mom," Annabel's dormant femininity is suddenly released, from dancing in the mirror to flirting with Boris, the cute guy from across the street. In short, she's not really freaking out as most would expect...

Ellen, as Annabel, is basically sabotaged from the start, tasked with performing in a marching band, winning a hockey game for her [daughter's] team, and later, water skiing at "Dad's" aquacade. She has no idea how to do any of these things. A good day to skip class?

Mom sorta gets the last laugh--after school, she completes the shopper's circuit, dolling her daughter up into someone not completely divorced from "gorgeous."

"Dad" is a nebulous character, leaving audiences unsure whether he's respectable or despicable depending on the scene. Annabel even refers to him as a pig and chauvinist (oink, oink) on multiple occasions. To be fair, maybe Dad is just guilty of having high expectations for his supremely capable housewife.

Annabel has her struggles...but also her successes, including finding some bonding time with "Ape Face," her obnoxious but otherwise loving brother.

Mom and daughter are reunited in a rare but genuine show of affection--they better understand each other now. Mom knows Annabel's life isn't trivial, and Annabel learns that taking some personal pride in one's demeanor is worth the added effort.

The films ends with father and son having a dispute not unlike the mom/daughter misunderstanding from earlier. Hints of a sequel?

In a twist (mostly) unique to this version, when Annabel and Ellen switch back, their bodies, not their minds, transport to the appropriate locations. In short, that's "Mom" on top. And after the switch, that's Mom on the bottom.

Freaky Friday 1995: Softer Daughter, Single Mom

Freaky Friday ’76 would inspire a number of copycats and similarly-themed films. Vice Versa. Like Father Like Son. Big. The difference, really, was in the chromosome; while Freaky Friday explored the fun and foibles of being a girl, these later movies explored matters from a more male perspective, often with an added element of adventure or maturity. But the pendulum would swing back in 1995; Freaky Friday’s tall tale would be reincorporated into an official Disney Channel remake. It’s the “lost daughter” of the franchise foursome, a Shelley Long-led swap that faded soon after its airdate. As of early 2024, it can’t be streamed or purchased on disc. It only exists, thanks to some preservation-minded saints, on YouTube in rather grainy, VHS-esque form.

And no doubt, when compared to its Freaky counterparts, this is the least flashy—the most-budget—entry in the franchise. Like any TV movie, it feels small and constrained…lacking the wacky, free-wheeling nature of the original film while robbed of the polish and cinematic tricks of its 2003 successor. And yet, sometimes less is more; the Freaky Friday of 1995 might be more limited and less ridiculous, but that also means a story that feels more grounded than its rivals. If not better, exactly...then at least a smidge more believable.

The basic plot mirrors the ’76 classic with one key difference: Ellen is now a single-mom juggling family, a (almost) fiancé, and a burgeoning career in fashion design. If Dad was a bit of a chauvinist in the first film, “would-be Dad” is more of an exasperated interloper here, especially once mom and daughter make their wouldn’t-it-be-nice-to-have-her-life” switcheroo. While the original film was indifferent to the mystical cause behind the mother/daughter crisscross, this version puts the blame on a couple of (conveniently acquired) magical talismans. Once Annabelle and Ellen make their fateful, envious wishes, they’re instantly warped into each other’s body for a day of zany misunderstandings.

There’s no competing with a classic, so goes the saying. And here, the adage holds true—this remix of the Freaky mythos doesn’t quite capture the raw, fantastic madness of its predecessor, nor are its leads quite as memorable. No crazy car chases. No mother—as daughter—making a complete fool of herself at school. No daughter—as mom—overtly flirting with the teen across the street. And definitely no girl now celebrating that she’s become her much older mother.

Rather, Freaky ’95 plays the game a bit straighter, losing some laughs but gaining a modicum of extra credibility. Sort of. Ellen handles middle school with general aplomb, if one can overlook her lighting up a cigarette in front of the school principal (an inexplicable but still funny scene). Her success makes sense considering she has been to school before. And the social dynamics, one would think, wouldn’t have changed that much in twenty-some years…teachers, boys, and mean girls come with the realities of any period. Annabelle is the one who truly struggles, having to suddenly command Ellen’s hectic fashion business without having a lick of experience. This also makes sense—an adult has experience being a kid, but a kid has no business being an adult.

The inevitable question is whether the movie competes, even remotely, with the 2003 redo, which blatantly takes some of its ideas (the single-mother dynamic being the big one) while still sharing the same millennial-era sensibilities. Indeed, both films are spared the smart phone/social networking renaissance of the late 2000s, giving them a more timeless vibe. Lohan’s film, of course, is more “fun,” enjoying a wildly bigger budget, big-name stars, and a catchy soundtrack—it’s the popular, flashy teen to Freaky 1995’s modest, less-privileged kid. But the latter does have its classy, classic moments: Annabelle’s conflict with her school rival is settled with a satisfying, “let’s work together” compromise that feels very Disney, and her brother’s bullies receiving a fitting smackdown at her (Mom’s) hands is also entertaining. The Lohan film disappoints on both accounts.

The movie, especially for Freaky fans, is definitely worth a watch. Being made for the small screen, it lacks the proper resources to compete with its theatrical cousins, but that doesn’t mean it should remain buried. If Disney had any shame, it would immediately jump to include this on its Disney+ service, or even better, develop a four-film disc boxset that justly reincorporates this as the second film in the “canon.” Until then, cinephiles are left with only the film’s faded remains on YouTube. And that’s a reality truly worth freaking out about.--D

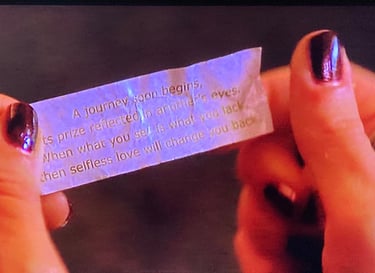

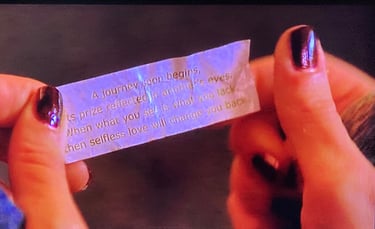

A pair of magical talismans are the guilty MacGuffins here. Although not a brilliant conceit, the items at least provide some kind of insight into the Mother/Daughter flipflop. Both the 2003 and 2018 films follow the same precedent, using fortune cookies and a pair of hourglasses, respectively. Only here, however, does the switch threaten to be permanent.

Annabelle isn't exactly genteel in this version, either, as seen in her outward hostility towards her brother. All in all, however, this Anna is a bit nicer, and a bit easier on the eyes, than her mousy '76 counterpart.

Beyond the obvious problem of being switched, both Annabelle and Ellen are given secondary hangups to overcome. For the daughter, she has a mean-girl, diving-team rival. For the mother, she has a freaky fear of heights.

In theory, "Ellen" overcomes her fear of heights once she's forced to climb the diving tower.

Annabelle, as Ellen, has a heart-to-heart with her teen rival...and both develop a sense about being a good friend and teammate.

In many ways, Ellen--as her daughter-- proves to be the true "rebel" of the two. Despite her more goody-goody pretensions, she crusades against dissecting frogs in science class, lights up before the principal (while in her office, at that), and even steals a kiss with Annabelle's heartthrob. Not a bad day's work, you little scoundrel.

Annabelle, as Mom, is left generally clueless...having to fire an employee, devise a new clothing line, and sell a fashionista on financing Ellen's future fashion ambitions.

Freaky '95 is the only version is which the (would-be) fiance is actually told of the switcheroo. He eventually helps get the two reversed.

Annabelle, in Mommy's body, roughs up her brother's bullies. It's a scene unlike any in the entire franchise. And a good one.

The movie also has a mystery/sleuthing element, with Ellen (as Annabelle) running around, trying to piece together the reason, and cure, for their inexplicable switch.

Freaky Friday 2003: Bigger Budget, Bigger Bombshells

Almost twenty years passed by—an entire generation, in essence—before Freaky Friday received its first remake. But it’d be only eight years until the next redo, a Lindsey Lohan-fueled spectacle that banished the 1995 reboot far behind in the rearview mirror…all the while lifting some of its ideas. Indeed, was another attempt at the concept just too little, too soon? Had there been enough of a generational leap for yet another teen-becomes-mom debacle?

Not really. Although the Internet and the cell phone were a thing by 2003, the century’s turn was still more in line with 1995 than the world of, say, 2011—the era of smartphones and burgeoning social media. Once could argue that Freaky Friday 2003 came too soon, feels too redundant…should have waited for a greater cultural juxtaposition with the movie before. A "Freaky 2014", with all its quick cultural shifts and subversions, would have better contrasted with those “primitive” 1990s--forcing an old-fashioned mom to switch with her tech-sophisticate of a daughter.

Of course, waiting would have meant no Lohan. Or, probably, Jamie Lee Curtis. Both of whom channel each other’s character here with an accuracy lacking in the earlier two versions. While Barbara Harris’ Annabel-as-Mom portrayal is excellent, it never felt she was the Annabel as shown in the film’s earliest scenes; Harris was playing the typical teen, and Jodie Foster’s Annabel was anything but the stereotypical norm. Shelley Long’s Annabelle portrayal is similar—an accurate distillation of a young girl, but not necessarily of the specific teen she was supposedly hosting.

Freaky ‘03 somewhat dodges this problem, thanks in part to the acting pair’s smarter performances, but also to a script that wisely raises Anna’s (not Annabel this time) age to fifteen. Moved closer to adulthood, seeing Curtis pantomime as Anna feels more genuine. Likewise, Lohan’s more deliberate performance when channeling the mother (now renamed Tess) works believably enough.

The story isn’t perfect, of course. As in the previous versions, Anna remains an atypical teen, her self-serious nature an unfortunate dampener that undermines Curtis’ more flamboyant portrayal. Unavoidably, the scenes where Curtis cuts loose the most—acts most like a giddy school girl—is when the facade noticeably slips, revealing the actress having fun versus the helpless, miserable teen supposedly trapped within. The movie also flounders with its secondary characters, most noticeably Anna’s high school nemesis and her younger brother. The former never receives a proper resolution or comeuppance, the latter never has his bullying problem approached or resolved. Moreover, a new “Grandpa” character has been added to the mix; he’s good for a few easy laughs but doesn’t really need to be there.

But the movie isn’t about them. The reason to watch is for the Lohan/Curtis dynamic, plus a script that better establishes the pain—the hurt feelings and the disappointments—both characters hold against the other. It’s subtle, but Anna is still reeling from losing her father (in an unexplained death) three years prior, and can’t understand how her mother would want another man, and a fiancé at that, so fast. Tess, for her part, can’t fathom why Anna isn’t more on her side, is so unwilling to offer consolation or support. It’s a convincing psychological twist that the earlier movies never capture. And unlike those versions, 2003’s Freaky actually sees Mom and Daughter joining up throughout the film, the two desperate to uncover the cause of their switch and a way to swap back (never trust a fortune cookie). At one point, Anna, trapped as Mom, even cries on the shoulder of her much shorter counterpart, despairing over their freaky predicament. It’s a fitting reaction, and true to how most girls would behave under similar circumstances.

Is there a perfect Freaky Friday? No, and it has less to do with actors or directors or ridiculous scripts, and more to the premise itself. Despite what the three movies may or may not suggest, swapping with Mom isn’t fun. Wouldn’t be funny. It’d be scary. Horrific. Gross. The films emphasize the comedic side of the problem, ignoring or sidelining the true, horrible horror looming on the periphery. What if Mom and Daughter never switch back? What would it be like to be Mom, a fifty-year-old woman, not for a day, but for a lifetime? While she gets to be young and pretty again?

Like, total scare of a nightmare, right?

That question, that lurking horror, is never fully acknowledged, a decision that preserves the comedy but robs the authenticity. No version of Annabelle and Ellen’s predicament feels entirely honest. The tension is just a mention, the suspense all but missing.

Freaky Friday, it seems, can’t be too freaky. Just inconvenient. Awkward. And a teeny bit kinky.--D

Interestingly, Freaky '03 is the only version to follow the cliche of "awakening the next morning" in the other's body. The funny "bosom shot" of the original film gets an homage here with a nice slice of Lohan's butt.

Freaky '03 posed a problem: What does a writer do with a character who's not supposed to be overly feminine, but is being played by the hot Lindsay Lohan? Make her a guitar player in a punk/rock band, of course! Best of both worlds, right?

The gimmick, this time, is a pair of fortune cookies, administered by a mischievous Asian woman. Although her meddling ultimately strikes a stronger bond between daughter and mom, one wonders how many other lives she's interfered with...and possibly wrecked.

Once swapped, Mom tries to improve her daughter's lot, including calling out a vindictive teacher's bad behavior. Anna, on the other hand, gives Mom a butch haircut and a set of new, ostentatious duds.

Unlike the earlier films, the two leads actually cross paths multiple times. They soon learn the awful truth...they may not be switching back before Tess' wedding the next day. And yep, fittingly, Anna freaks.

As in the other films, there's some criss-crossing with the daughter's love interest. The world is still waiting, however, for the steamy reversed version where the daughter gets the hots for Mom's fiance...

Anna's rival, unlike the '95 version, is poorly developed, basically being mean to be mean (without explanation). As for the brother, he's cute but has little to do--the teacher/parent conference is even given to him (instead of Anna) just to force an arc between the two siblings.

Having Tess and Anna team up for the movie's big climax--a music audition happening concurrently with Tess' wedding reception--is a nice touch, and one of the movie's stronger moments.

Believe it or not, a tentative sequel was planned for the boy and his bumbling grandpa. Yep, these two were due for their own switcheroo--perhaps it's a blessing for all involved that this never happened. (A more proper sequel, as of 2024, is in the works for both Lohan and Curtis, the latter who's now grandma age.)

Freaky Friday 2018: Sloppy Story, Saucy Songs

If one assumed the “Freaky” franchise would conclude with the 2003 remake, they’d absolutely freak to know that another exists…

In 2018, as a Disney Channel exclusive, the Freaky series would return for a fourth exploration into the mom-and-daughter swaptacular. At this point, was there anything left to dredge from the concept? Had enough time passed to justify revisiting the premise yet again?

Superficially, yes, a case could be made. The 2003 film, with its absence of smart phones and tablets and social networking, feels more like a creature of the 1990s. But in the 2018 attempt, advanced tech is everywhere. Teens are now gadget-savvy and gizmo-dependent. By default, this is the most “modern” version of the saga, and thus, perhaps the most relatable for those of a Generation Z persuasion.

And yet, all the gadgets and flashy apps aside, the movie also feels a scant old-fashioned. A tad old school. Old. And that’s because, for reasons, Disney took the old switcheroo trope and attached some song, added some dance. Yes, Freaky ’18 is a musical—an adaptation of the off-Broadway stage production.

The movie begins innocently enough, with Annabelle, er, Ellie this time, flopped atop her bed, looking miserable as her two besties (also on the bed) observe in similar mopey fashion. Perhaps not surprisingly, Ellie is upset with her mother, and really, at life in general. And like her 1976 counterpart, this iteration of the daughter is a bit caustic. Definitely a slob. Not particularly likable.

Downstairs, Mom—now known as Katherine in this version—is akin to what fans of the franchise would expect. She’s cordial, organized, civilized, and doesn’t understand why her daughter is so hostile. So slovenly. Again, unbelievably unlikable.

The movie is, in many ways, a grab bag of the ’95 and ’03 versions. Dad has passed. Mom is engaged to another man. And Annabelle/Anna/Ellie/whatever is unhappy with the current state of her life. Eventually, as the story proceeds through its wheel of family strife and mistaken identity and impending reconciliation, audiences learn that Ellie’s bad disposition is a symptom of her lingering grief. She still misses her dad.

But much of this drama is lost, sabotaged even, due to the many cheeky songs that soon croon throughout the picture. Like most musicals, these dance numbers are outlandish dishes of ham…sometimes tasty, always cheesy. One particular ditty—“I Got This”—is the perfect straddling of these two extremes, with the now-switched mom and daughter proclaiming their spicy, icy pride in mimicking the other’s life. How hard can it be, they foolishly think.

Not that the exchange was ever fair, exactly; no matter the version, Mom gets the obvious, flirty benefits of youth, while the teen receives all the wrinkles and aches of middle-age. At least, sort of…becoming Jamie Lee Curtis or Shelley Long isn’t the worst of fates. But this version has the decidedly less-extravagant Heidi Blickenstaff playing the parent, bringing as much frump as fantasy to the role. An unhappy daughter could probably stand being Barbara Harris for a day, but the heftier Blickenstaff doesn’t quite instill the same wish or fetish.

Which is not to knock the two leads’ performances. Ellie’s Cozi Zuehlsdorff proves especially versatile, switching between bitter teenager and blissful mother with equal parts mope and maturity. Blickenstaff is also capable, although her “Ellie” sometimes feels too overwrought, too whiny, as if she’s channeling an 8-year-old girl more than a grumpy teen. It’s not a problem unique to the series—the adult actresses of all four films tend to overplay the daughter they’re embodying, probably for theatrical or comedic effect…but at the detriment of full believability.

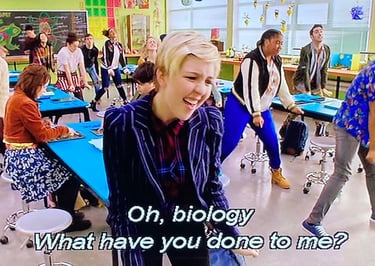

And believability, beyond the odd songs (Oh, Biology is incredible for all the wrong reasons) and awkward casting, is the movie’s primary flaw. After mom and daughter swap due to the machinations of a magical hourglass (given as a gift, for some reason, by Ellie’s deceased father), Katherine scampers off to school in her child’s body, happy to live a day as a squeaky-clean teen while Ellie has to fret with the details of her mother’s approaching wedding. Matters get worse (and weirder) when Ellie, in Mom’s body, sings a woeful tune to her little brother about the duplicitous nature of parents, implying his dreams are childish and pointless. Said brother then runs away, causing a panic, and is then retrieved conveniently by Ellie’s "awe shucks" love interest from school. Later, Katherine—still in her daughter’s body—joins “The Hunt,” an annual scavenger contest that sees mobs of teenagers ravaging the city, ransacking stores, bowling alleys, and amusement parks for the specific loot they need. Not only does Katherine place first against the ridiculous odds, she also conveniently locates the second magical hourglass needed to reverse her “switched” condition. And what’s Ellie doing while Mom has her night of fun? Sleeping? Crying? Practicing her mom’s wedding vows? Who knows.

It’s a poor final act for a movie that, despite the musical absurdity, has its moments of magic. Katherine, loving the freedom her new teenage body entails, performs a cartwheel while Ellie’s friends watch with derision; she gets the hots for her daughter’s (almost) boyfriend; she argues with her mirror-reflection, getting confused which identity—mom or daughter—she really is. There’s also a great scene in which the switched Ellie and Katherine bicker, to hilarious effect, during a parent-teacher conference.

But are those cute, sometimes unseemly moments enough to redeem an unlikable, mean-spirited Ellie and a plot more driven by music than sense? Actually, yeah, maybe. It’d be easy, at least, to put this TV movie ahead of the long-buried 1995 revamp. But while that ‘90s movie felt almost too low-key for its own good, this one goes overboard with the full-bore flamboyance—switching what was already a ludicrous premise into full, unapologetic kitsch.

Freaky Friday ‘18’s legacy is a dubious one, perhaps doomed to suffer the faded fate of its ’95 predecessor. And truthfully, that may even be for the best. It’s not a great film, merely suffices as a musical, and feels completely unnecessary next to the 2003 semi-classic.

Yet, it’s also fantastically weird. Boasts some real talent. And, with its unapologetic combination of song and schlock, offers something different. Distinct. Flawed but fun.

This is the quintessential ‘B’ movie, essentially. And that grade, at least, is better than a freakin’ 'F'.—D

In this version, the switcheroo comes via a naughty hourglass: what the "sands of time" have to do with bodyswapping, however, is another matter.

The movie has its share of funny lines. Here, after being switched, Mom describes her new body as akin to being a "sad little boy." It's funny because it's true.

Per the lyrics of the initial song, it seems the fateful switch will expire within a day...as little as 12 hours. But nope, only by retrieving a second magical hourglass (also given by Dad) can the errant wish be reversed.

The second song "I Got This" is perhaps the film's finest, with both Mom and Daughter insisting they'll be just fine living the other's life. It's a catchy ditty, even if it's supremely weird to see the mother happily marching off to school, ditching the details of her wedding to the clueless, useless daughter.

The Freaky Friday series likes its third-act climaxes, from water skiing debacles to rock concert auditions. This time, it's "The Hunt," a bizarre all-night scavenger free-for-all that Ellie really wants to join--despite it being on the eve of her Mother's wedding. Not surprisingly, Mom says "no." OMG, she's like, so unfair!

Ellie, the daughter, makes a bad first impression. Sloppy, condescending, and outright hateful, she's a difficult character to root for no matter the body she's condescending from. In the bottom shot, while possessing Mom, she even crushes her little bro's dreams of becoming a magician.

Katherine, riding high on the gifts of her daughter's body, has the more entertaining part of the picture; whether intended or not, her "Ellie" is leagues more endearing than the "real" one. Indeed, even the school heartthrob agrees, inspiring the film's weirdest (creepiest?) song, Oh, Biology.

Ostensibly, the movie is like the others--Mom and Daughter don't understand each other, don't respect each other, don't relate to each other. But to this script's credit, the problem isn't limited to youth versus wisdom, but unconditional (yet unrequited) love. Until Ellie can openly express affection to her mother, they'll never switch back.

Ellie's hair comes to represent the mindset/psyche of both characters, the front wisp pinned elegantly for Mom, but falling without style for the daughter. The conclusion, once Ellie has switched back, suggests a compromise between the extremes.

One funny scene has Mom arguing with herself, getting confused over whom she even is: Ellie or Katherine? The movie is full of these little ideas that aren't explored for more than a gag or a song...but what would happen if one became their hot daughter for just a little too long? Who began liking it just a little too much?

Contact: lostnostalgiaproductions@gmail.com

Website: www.lostnostalgia.com

Like what we're doing? Please consider throwing us a dollar into our Patreon page's tip jar!