Grimm's Fairy Tale Classics

Season 2 Per-Episode Reviews!

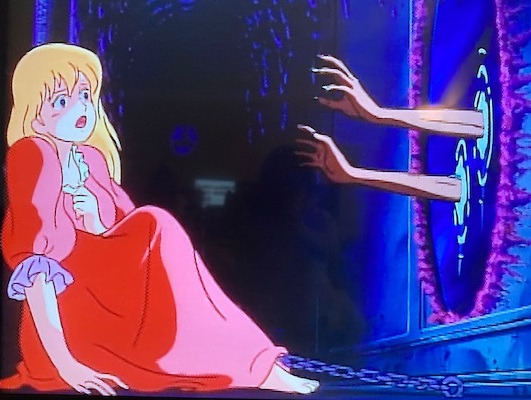

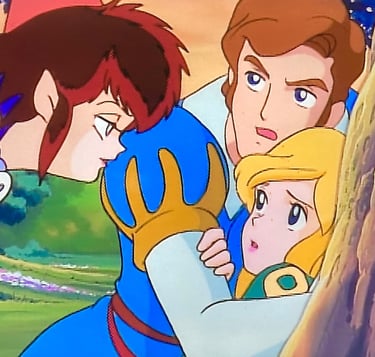

Episode 1 – The Crystal Ball

First-time viewers expecting Disney-fied, whimsical retellings of old, creepy folklore will quickly learn otherwise in this second-season opener. Antoine, the youngest of three brothers, makes a gruesome late-night discovery—his beautiful mother, now a cackling old hag, is holding a beautiful princess prisoner within a magic mirror. Horrified, he watches as the witch drags the screaming maiden out from the glass and proceeds to happily drain her lifeforce. The girl is then tossed back, withered like an old husk of corn. Yes, it’s pure nightmare fuel.

Worse, the old crone, now a beautiful woman again, learns of Antoine’s discovery and swiftly exacts her revenge, transforming his brothers into hapless beasts. Only Antoine escapes the woman’s magical gaze, but that just means he must return to save the girl and, presumably, slay his demonic mother. Nothing like a righteous quest of matricide to complement those notions of abuse and child enslavement!

Freaky themes aside, though, this is a satisfying episode full of archetypal heroes and villains and grateful maidens waiting at the end. The story doesn’t always make complete sense, of course—like many fairy tales from ages past, the how’s and why’s are less important than the setup and the outcome. Antoine saving the princess and achieving justice is what matter most; those expecting an exploration on the psychological ramifications of a son terminating his own mother will be left disappointed. By fairy tale logic, a witch is a witch, mother or not; feelings of filial love or loyalty are instantly scratched once the mother’s true nature is known. Same with the grand climax—no conflicting thoughts, no sorrow in the aftermath. What must be done, be done. No regrets.

Cue the happy ending.

And in that sense, perhaps this tale is somewhat sanitized, after all, much like when Rapunzel shrugs off the death of her own wicked “mother” in Disney’s Tangled. But while that film is still a fun romp meant to be enjoyed by everyone, The Crystal Ball’s happy ending doesn’t make it any less of a nightmare. Night-time viewers beware.--D

Episode 2 – The Marriage of Mrs. Fox

If the last episode was a parable born of paranoia—that murky, secret unease children bear against the hidden lives of their parents—this episode takes the opposite approach, examining suspicion not through childhood psychosis, but through simple, untenable jealousy.

Indeed, episode 2’s wacky, anthropomorphic cast and slapstick-stylings make a strange contrast to the first’s grim proceedings—Mr. Fox is just that, a proud, nine-tailed fox obsessed with his many successes. He has wealth, comfort, and most importantly, a beautiful wife—he’s the greatest and luckiest of his kind, or so he believes! But the darker side of his consciousness soon poses an unsettling thought; how does Mr. Fox know, really know, his wife is being true and faithful?

He laughs off the notion at first, but over time, paranoia gets the better of him and he concocts a ridiculous plan. By faking his own death, he’ll see for himself whether his wife will run to someone else.

If none of this sounds sensible, plausible, even sensical…it isn’t. After faking a heart attack and being pronounced dead by his wife’s housekeeper, Mr. Fox’s body is just strewn to the living room floor as his wife mourns upstairs and the maid continues her household chores. And soon—very soon—a bevy of suitors are already at the door, each anxious to claim Mrs. Fox for themselves. As a corpse (laid maybe ten feet away from the door), Mr. Fox slyly watches, waiting to see if his wife accepts a proposal.

Except, one wonders, so what if she does? If he’s dead, can’t she remarry whomever she wants? And once another suave, nine-tailed fox shows up, she chooses to do exactly that. Predictably, this enrages Mr. Fox and, after revealing his ruse, he runs everyone violently off. Out his house. Out of his life. Only afterward does he realize his folly.

So…what is the moral of the story? The proceedings are so jumbled and poorly executed, it’s hard to know, but perhaps the true message goes beyond simple issues of trust. Consider Mrs. Fox—although not unfaithful, she wastes no time finding another mate. Convenience and comfort and prestige are obviously her chief concerns, not earnest relationship-building. Had this been what Mr. Fox wanted to verify from the start—a way to measure the sincerity of her love—this could have been a sentimental fable about commitment and the realities of marriage. Or, in the other direction, a satire on the superficial nature of relationships intermingled with high snob-riety.

Rather, we get a tall tale that, sadly, says nothing at all.--D

Episode 3 – Beauty and the Beast

If Grimm’s Fairy Tales is anything, it’s eclectic; the series introduced children of its day to a plethora of new stories and adventures extending far beyond the standard tales reiterated by Disney and popular culture. But not here. After receiving a yarn of nightmares and one of farce, episode three brings some familiar relief in Beauty and the Beast—a pleasant if somewhat predictable retelling of the time-weathered classic.

The story opens with a father leaving on a business trip. He intends to bring back a gift for each of his three daughters, but his youngest, the sweet-natured Maria, asks for only a rose. It’s a humble request made by an unassuming girl.

Except, the father soon learns, roses don’t grow in the winter! Desperate, he happens upon an enchanted mansion with a courtyard full of the crimson blooms. But plucking just one proves almost fatal when the mansion’s beastly proprietor arrives and proposes a deal—the father’s life, or his youngest daughter’s hand in marriage. What follows is the well-known parable of seeing through outward appearances to love the soul inside.

Adapted a few years before Disney’s own 1991 epic retelling, comparisons between the two works are inevitable…if a little pointless. Backed by a budget of millions and armed with Animation’s leading craftsmen, Disney’s film was always destined to be the celebrated, quintessential version. This twenty-minute, essentially low-budget short can’t hope to compete with the American machine, but like the Beast himself, it holds an unseemly sweetness beneath the rough exterior. The story’s slice-of-life flow and mellow pacing make this a quiet delight in its own right.

Perhaps a more subversive message, however, lies beyond this nod to inner beauty. Remember that, in almost every telling, Belle/Beauty/Maria aren’t aware of the Beast’s true, human form. For all Maria knows, the Beast really is a wolf or monster or alien or otherwise separate species. And yet, her desire for him blooms all the same. Is this, then, the fable’s true (or truest) message for those willing to look? That true love can transcend more than the form—even the species?

Could he have, one wonders, remained a beast?--D

Episode 4 – The Magic Heart

The Magic Heart begins like an origin tale for a superhero. Frederick, a young hunter searching fruitlessly in a wood, meets a hungry old man instead. Frederick offers his lunch to the gentleman and is given a valuable tip in return: Up on a certain cliff, he’s told, there’s a magic teleportation cloak waiting for the taking. Furthermore, by killing one of the ravens living in the adjacent trees, he’ll procure a magic pearl that can grant endless riches. Frederick soon seeks the loot and, finding the old man’s words true, proceeds to have many a grand, swashbuckling adventure.

Well, not really. Scratch that second part.

Rather, a witch and her beautiful apprentice deceive Frederick almost immediately, stealing his treasures while abandoning him to a scalding desert. The remaining beats of the story has the hero returning to exact his revenge in typical, and rather convenient, fairy tale fashion.

And convenient is the operative word. This is a multi-faceted tale that, despite the creative possibilities offered, opts to embrace the typical evil witch routine along with an ending that doesn’t feel wholly earned. The third act is largely to blame, offering Frederick a series of “freebies,” so to speak—lucky contrivances that get him out of the desert and back home for some easy, last-second vengeance before the show's credits roll.

Nevertheless, it’s still an entertaining sequence of events, a fun juxtaposition between Frederick’s cavalier naiveté and the general creepiness—the sense that something sinister is afoot—seeping into each scene. In one such moment, the comely apprentice is shown playing with some adorable sparrows, singing gaily like a blonde Snow White. A moment later, however, she transforms the birds into slippery snakes, giggling merrily as they slither away. It’s a weird, subversive moment that signals something is very wrong…but which never receives a proper payoff.

A missed opportunity? Perhaps.

Or, maybe, a sparing mercy.--D

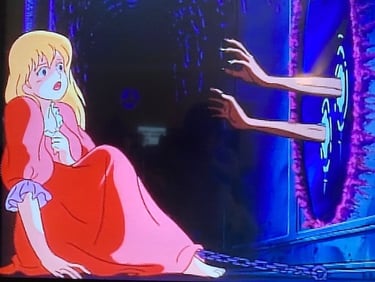

Episode 5 – Rapunzel

Like Beauty and the Beast before it, it’s hard not to judge any rendition of Rapunzel without immediately comparing it to Disney’s Tangled, a film that nearly mangles the source material beyond recognition. This version is a more faithful adaptation, yet still inflates certain scenes and expands certain characters to, presumably, stretch the runtime on a story that would otherwise conclude by the first commercial.

Indeed, the story takes its time even introducing the titular character, opening rather on Rapunzel’s pregnant mother stricken with a desperate hankering for some garden-plucked lettuce. Lettuce, naturally, that can only be found on the property of the kingdom’s resident evil witch. The wife’s husband, for good reason, would rather not steal from a crone who could zap him to ash or worse, but after being repeatedly pestered and shamed by his wife, he finally sneaks out at night and commits the deed. Twice, actually. And on the second attempt, he gets caught. If he doesn’t want to be transformed into a mutt, he’s told, he’ll have to give up his first born—the still-in-the-womb Rapunzel.

It’s an overly elaborate setup that, in truth, is probably the most entertaining segment of the story, as watching the poor husband be browbeaten by his petulant wife is both humorous and surprisingly convincing. It’s slightly strange, then, that these characters are then removed from the story once Rapunzel is taken away. Sixteen years later, Rapunzel is a healthy but unhappy teen trapped high in the witch’s impenetrable tower, knowing little beyond the chamber she’s held within. And unlike her Tangled counterpart who’s reimagined as a dynamic, cheerful force with plenty to do, this Rapunzel carries a quiet sadness that, although not as immediately endearing, is probably more realistic.

The story ends with a prince, of course, his presence rendering poor Rapunzel largely irrelevant in the closing scenes. It’s a strange irony that makes more sense on reflection, for without any kind of real-world experience, there’s simply not much for the girl to do; the plot has no choice but to claim another anchor character. Like Princess Zelda in, well, The Legend of Zelda--a character largely overshadowed by the heroic Link--this fairy tale is better read as The Legend of Rapunzel; it’s more about the circumstances surrounding the girl than an inside look into her life.

Disney used contrivance and convenience to fix this dilemma in its own retelling, changing the story until it was an almost entirely different fable. It’s a story about a girl who happens to be named Rapunzel, not “The Rapunzel Story” of classic legend.

Which means neither version (and maybe any retelling) truly does Rapunzel right. One replaces her with a doppelganger imbued with the indomitable qualities expected in the modern, idealized girl, the other treats her like an old-school plot device.

One overwrites, the other sidelines.--D

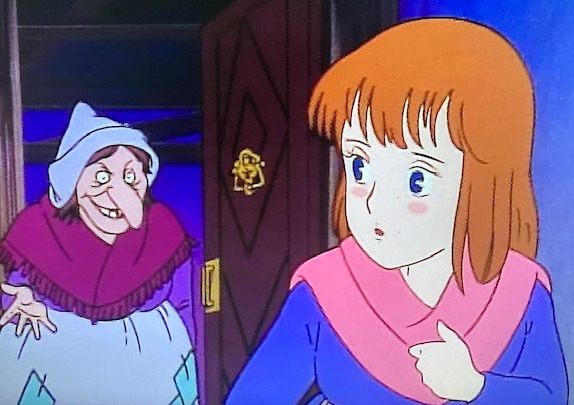

Episode 6 – The Old Woman in the Woods

“The Witch in the Woods” would have been the better title, as that’s the true crux of this rather trippy tale. It opens on a royal caravan filled with an assortment of fat, rich, entitled types all wallowing in oblivious self-indulgence. Flanking their stagecoach is the help—guardsman on horseback and, at the rear, a more modest carriage overcrowded with servants. One of these folk, a girl named Lisbeth, yearns to be a princess herself.

And then, as the procession enters into a forest, disaster strikes. A witch appears out of nowhere and, for no apparent reason beyond pure evil glee, obliterates the troupe, turning most of the poor souls into ghastly, gangly trees. It evokes the same nihilistic terror found in episode one’s The Crystal Ball, for there is no poetic justice here. Yes, the pompous royals in their fancy-schmancy garments receive their due treatment, converted into identically gray, garish stalks existing only to extend the witch’s monstrous forest. But their entourage—simple people glumly doing their jobs—receive the same rebuke. Good or bad, welcome to the wood! This witch is an equal-opportunity employer.

But one soul does escape; young Lisbeth runs away, narrowly escaping the others’ fate but also becoming hopelessly lost. Tired, hungry, and in constant danger of being devoured by wolves and other beasts, she falls into understandable despair. Only then, via convenient fairy-tale means, does an angelic white owl appear—speaking kindly, he materializes magical keys that allow Lisbeth to unlock certain rocks and trees as one might open a chest or door, revealing food, shelter, and other treasures. It’s all imaginative but completely inexplicable.

Unsurprisingly, this owl is later revealed to be a cursed soul himself, another victim of the witch’s cruelty. Why he’s an owl and not a tree is never explained, but Lisbeth, anxious to break the spell all the same, enters the witch’s castle in a climactic, rather mind-bending final reckoning. It’s an action-packed closing act without much logical progression, lending to the sense that the writers were just making things up as they crafted each scene. Even the narrator likens the proceedings to a shifting funhouse. And yet, it’s this very element of unpredictability that also makes the episode a worthy watch.

Finally, Lisbeth herself deserves a special note. Cute, impulsive, and a little awkward, she packs more personality that the typical genteel, fairy tale damsel. From manically devouring a loaf of bread to floundering gracelessly in the face of danger, she possesses a slightly goofy, almost clownish charm.

A metaphor, perhaps, against the pomp and artificiality of her faux superiors.--D

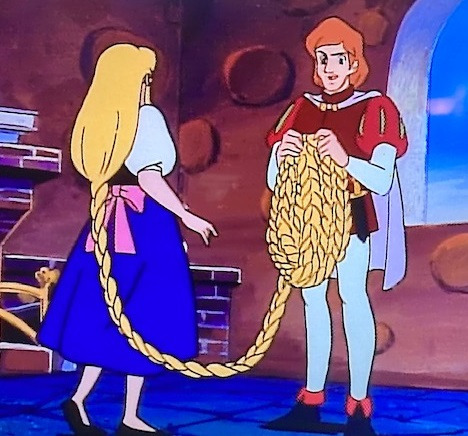

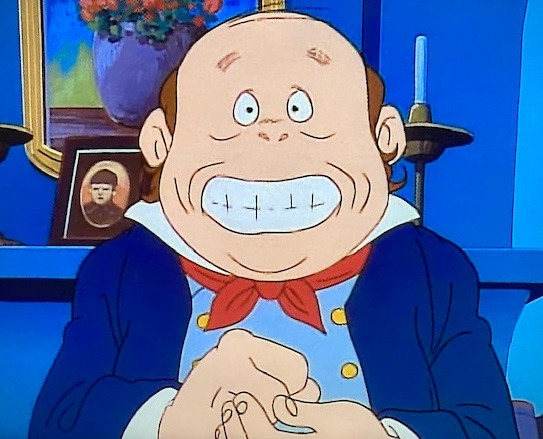

Episode 7 – The Faithful Watchmen

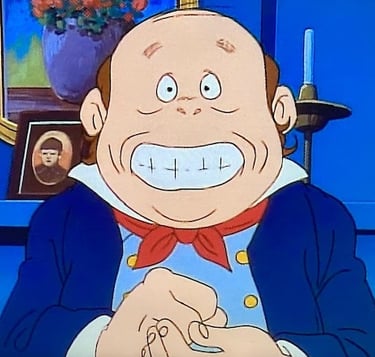

In a series already punctuated by some excellent storytelling, special mention must go to the show’s captivating art direction. Although obvious now, when the series premiered in ‘90s-era Western markets, viewers were largely unfamiliar with the anime aesthetic; indeed, these fairy tale retellings could well have been a child’s first exposure to the beauty and versatility that is Eastern Animation. The show stood as a shrewd fusion of Western myth and Eastern whim, unrecognized then and underappreciated now.

This versatility is especially evident here, an episode that drops the more traditional anime flavor for those of a rounder, more exaggerated style—something more akin, one could say, to a classic Western studio like Rankin/Bass. And it works, the cartoon-ified” approach depicting the story’s oafish lead—a greedy, irredeemable landowner—quite artfully. So greedy is he, in fact, that an opportunistic devil takes notice and, wanting the man for his own purposes, quickly foretells his death.

Seeing flames in his future, the landowner strikes a deal with a local farmer in exchange for some food; should he suddenly die, the farmer is to guard his grave for three consecutive nights. And yes, as if ordaining his own fate, the greedy baron soon dies thereafter. The poor farmer now has a fun promise to keep.

Although clearly a rebuke on the dangers of materialism and avarice, the story takes a quirky turn in its second half, morphing into an amusing fable of wits and irony more in keeping with the Aesop tradition. The farmer, now joined by a clever soldier, must outsmart the devil who’s come at last to collect his prize—the landowner’s soul. The moral already bared, what’s left is a classic battle-of-the-minds scenario as the two humans must somehow stall the demon until sunrise. And what they devise is both clever and fun.

Nevertheless, it’s the art that’s the star here, a testament to the sterling talents of its animators and craftsmen, plus the flexibility that the anime form affords. Characters stretch and fret and are ebullient with life, with the landowner himself so perfectly realized in his pompous absurdity, it’s a pity he dies so early.

It takes an awful character, it seems, to bring out an animator’s best.--D

Episode 8 – The Wolf and the Fox

Anthology shows face a unique challenge: Despite featuring storylines radically different in plot, tone and scope, they must still somehow maintain a consistent, and hopefully growing, viewership. The inimitable Twilight Zone, for example, deftly executes this precarious dance, offering suspenseful, satirical, or fantastical tales still gilded with a supernatural finish. Despite the regular thematic shifts and genre blurrings, it contains a unifying, transcendent quality that keeps people watching.

Grimm’s Fairy Tales Classics struggles for the same allure, stitching everything from horror to slapstick across a fantasy patchwork. Indeed, it’s knights and evil witches and epic struggles in one episode, talking donkeys and boot-wearing cats in the next. A kind of stark variety, some might say, that lacks Zone’s more unifying ingredients of irony and compelling moral messaging.

And this episode certainly highlights the problem. It’s innocuous enough, following the daily lives of a woodland wolf and fox, the former unable to catch even a simple rabbit, the latter successful in everything he does. In short, the wolf—always hungry, always down-on-his-luck, always alone—eventually bullies the fox into joining his “two-man pack,” all so he can enjoy the spoils of the fox’s hard work. This lasts until the fox concocts a scheme to forever liberate himself, and the forest, from this perpetual terror.

Except, the wolf isn’t particularly terrible. A buffoon perhaps and a bully for sure, but not so despicable that the viewer yearns for his outright demise. In fact, the wolf is portrayed so pathetically here—a loser defined more by bluster than bite—one could be excused for feeling, if just maybe, a little sorry for him.

And that’s a problem for a tale which needs its audience to hate the bad guy, if only to justify the so-called good guy’s actions at the end. It’s a straightforward story of comeuppance, but…might have this been better served as one of redemption? Of the wolf reforming his ways and learning the value of friendship?

But no, the story ends with the fox free and the wolf gone-- with little for the viewer to glean, it seems, but sweet revenge.

No irony and, certainly, no real moral.--D

Episode 9 – Mother Holle

The selfless maiden pitying the poor stranger…

That classic fairy tale trope has seen more than one virtuous girl find her true love and achieve a happier life. But what if that girl said “no” to those awards and returned to her glum, everyday existence? Welcome to Mother Holle.

The story opens with the comely Hildegard, a young girl forced to toil all day while her stepmother and sister live in lazy luxury. On one particularly frigid afternoon, Hildegard accidentally drops a spindle of thread into a 30-foot deep well. Fearing the wrath of her family, she plunges in after it, sinking endlessly until she awakens on the “other side.” No, it’s not the afterlife or the upside-down, but the sky itself now flipped right-side up. And at the center of this magical land is Mother Holle, a mystical old woman who, by literally shaking the down off her featherbed each morning, blankets the Earth with new layers of fallen snow.

She’s aware of Hildegard’s plight and, sympathetic, lets her stay as a housemaid. But, it’s not to last; the girl soon becomes homesick and, amazingly, actually asks to go back. Mother Holle obliges, but not before rewarding the girl with an apron full of gold.

Every fairy tale needs a compelling villain or conflict…a sense of urgency…a poignant conclusion. Mother Holle offers none of these, but finds a modicum of redemption by so handily subverting the usual fairy formula. The first is the creepy Mother Holle herself, who looks more akin to the typical storybook witch than a motherly, godly lady. She’s kindly but not warm, considerate but not maternal—an unapologetically old crone who still bears a sympathetic edge. Expect no heavenly angel hiding behind her ancient features; Mother Holle is exactly what she seems.

More significant is Hildegard’s confounding decision to go home—the same home-life that left her so terrified, she jumped down a well of hypothermia-inducing water. Is she really that desperate for a little affection? A hug? Sisterhood? A mother who loves her? Is Mother Holle failing to compensate for what Hildegard really needs?

And finally, remember those faithful tropes of finding true love and living happily ever after? Well, there’s no prince charming waiting for Hildegard here. Just two ungrateful taskmasters colder than the winter itself.

Hildegard still has her gold, but those coins are just crumbs. Her real need is love, a prayer which Mother Holle never answers.

And if a goddess won't...who will?--D

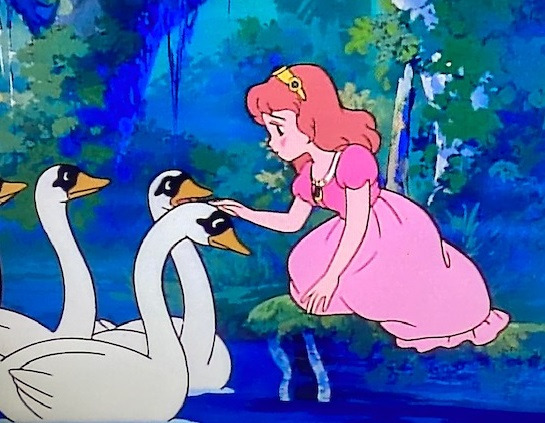

Episode 10 – The Six Swans

Creeping back to the series’ outright darker side, the show opens with a king separated from his subjects and lost to a sinister wood. Trees chase and gnash at him with apparent sentience and obscure all means of escape. His apparent savior comes in the form of an old crone who offers a way out—if he promises to marry her “daughter” in return. To his credit, the king seems to recognize this as the trap it surely is, but desperate, he makes the deal.

And yes, this bride-made-queen is the vilest of wives. She’s so dripping with evil, in fact, everyone senses her atrocious grossness long before her evil spree is even conceived. Her foremost targets are the king’s children whom she soon transforms into helpless swans via a flock of attacking, magic cloaks. She overlooks the young princess, however, who then dedicates herself to breaking the curse…and it’s no trivial matter, either. She must sew six shirts composed of chrysanthemum flowers over the next six years while living ascetically and remaining mute. Should she speak a single word or give an exclamation of joy, her efforts will be rendered, well, moot.

The story then progresses in somewhat inexplicable fashion—the king is never seen again, leaving the princess essentially abandoned to her family’s woodland retreat, sewing away in abject solitude. Until, a few years later, a neighboring prince spots the girl, falls in love, and makes her his queen despite the vow of silence. They eventually have a child and, not long after, the wicked queen returns for a final, brutal reckoning.

When viewed as a series of unnerving scenes enhanced further by its incredibly sadistic villain, this is a wonderfully macabre tale. But it’s also a story that feels hastily written as if scribbled to page in a single, uncritical draft—as if the storyteller was making it up as he went along without considering the basic tenets of logical plotting and progression. Consider: Even if the King had to marry this wicked woman, why couldn’t he render retribution once her evil actions were revealed? And since the Queen manifests seven enchanted cloaks but only turns six children into swans, shouldn’t the leftover garment immediately indicate that she missed the girl? And when the Prince asks his wife about her perpetual silence, couldn’t she simply explain the whole matter by writing it down?

But never mind. The story’s modest but courageous maiden transcends these oversights, proving a hero needn’t be born for the sword or endowed with power. It’s a lesson often lost in contemporary myths which treat their maidens like prettier men, putting action before compassion and thus missing the point entirely. The woman here—sister, daughter, wife, and mother—stands timeless if sadly anachronistic. A Lady of Peace and Quiet Self-sacrifice, a heroine be.

And a reminder that not all battles are won with brawn.--D

Episode 11 – The Coat of Many Colours

Vampires. Devils. Sadistic witches. These are the creatures that fill human fears. But as foul as these beasts often are, nothing beats the real-world horrors of a psychopath or murderer—especially when that lunatic is one’s own father.

And that’s the sordid story here; no witch or devil or evil curse to worry about, just a father’s abject madness as he rages after his horrified daughter. Why? His dying wife made him promise he’d only remarry a woman as beautiful as she. And when a proper candidate was never found, the father turned to his lovely daughter Aleia instead. It’s as disturbing as it seems.

To allay her father’s advances, the girl devised a clever scheme—she’d only marry the old king if he gave her a dress woven of silver moonbeams, a dress of stardust, and a cloak of a thousand furs. These were impossible tasks she knew he’d never complete. And yet, somehow he does…hence this story’s opening horror.

Fortunately, she takes the three magical garments and escapes; donning the heavy furs for warmth, she wanders unrecognized into a faraway land, now a vagabond among strangers. The kingdom’s prince, oblivious to her true status and taking pity, places her in the castle’s kitchen. And there, a heartwarming parable slowly unfolds.

It’s an artful juggle of opposite parts, a strange juxtaposition of subversive beginnings and jubilant ends. Despite a dark start, the story gently sighs into an almost anti-climactic, typical fairy tale ending. No epic struggles or risky wagers or triumphant comeuppances, just a sweet, slice-of-life love story that feels real and earned. A timeless light, and delight, for any era...dark or not.

A fan-favorite, and for a reason.--D

Episode 12 – Brother and Sister

Some tales are defined and remembered by their creative twists or surprise endings. Others hew to a more predictable path, offering a pleasant but ultimately underwhelming journey. Such is the case for Brother and Sister, a tale that neglects to even name its protagonists let alone offer any clever turns of its own.

The story is simple enough, with an older sister and younger brother fleeing their evil stepmother’s clutches and escaping into a nearby wood. But, oh! The stepmother is actually a witch who enchants the forest’s waterways. Through a mysterious voice that’s never explained, the sister learns of the curse and tries to convince her brother of the danger. But, thirsty and tired, the lad helps himself to a stream anyway, thus transforming into a helpless fawn. With nothing to be done, the two eventually settle in (a presumably safer) part the forest and, over the course of some years, create a reasonably happy home together.

As is the norm with these stories, a prince eventually comes, sees the girl, falls in love, and treats everyone to a happily ever after. Well, almost. In what is the story’s best attempt at providing a twist, the witch returns and whisks the new queen away, trapping her atop a treacherous mountain. Now, only through the power of love, can the prince hope to save her.

As seen, the story hits all the typical fairy tale tropes and plot points, but doesn’t offer much more. Indeed, for a story titled Brother and Sister, and one that sees said brother cursed and made dependent on everyone else, perhaps a better plot would have him, the lowly deer and not the mighty prince, brave everything to save his precious sister. The dear girl whom he had ignored and dismissed. The one who had cared and sacrificed for him, anyway. The one who could have left him to that forest, but didn’t.

Rather, the tale spins its yarn in the expected directions, weaving each plot thread around the prince being princely and the princess being distressed. And the brother essentially forgotten, dropped from the final act.

As if he were, well, just an animal.--D

Episode 13 – The Four Skillful Brothers

Less an outright fairy tale and more an adventure, the story opens on four young brothers leaving their impoverished homestead and heading out into the world, hoping to find some measure of success. And they do. Frans becomes a master thief, gaining almost superhuman speed and dexterity. Vilhelm gains a kind of second-sight, able to observe, and even see through, faraway things. George learns to be an expert marksman, capably hitting almost any target no matter the size and distance. And Peter becomes a peerless tailor, able to mend any material, from fabric to broken egg shells to literal planks of wood. When these brothers meet up after a year away, they prove themselves the perfect team.

And just in time! For a dragon has kidnapped the kingdom’s princess, and only through the brothers’ unique abilities is there a hope of bringing her back. So, the four venture forth, enduring a rough voyage and a battle against a terrible dragon. But there’s an even bigger problem at hand: if they prevail, who gets the girl?

It’s a strong premise somewhat squandered by an unambitious plot. A pity, really, when the possibilities are so vast. What if one of the brothers hadn’t gained a magical skill at all—only virtue—but after being laughed off by his siblings, he still saves them all in the end? Or, what if one brother’s skill had turned him evil, forcing his estranged brethren to put aside their differences to stop him? Or, what if one brother had failed to achieve the riches of his brothers but, after seeing the decadence wrought by their wealth, realizes he’s the lucky one?

Such poignant potential is traded here for a plot more akin to a Greco-Roman quest, what with its troubled voyage, heroic challenges, and a fair maiden waiting to be won. But the twist that is offered—who of the four is most deserving of the girl?—is a compelling conundrum in its own right, unpacking lessons on unity, humility, and brotherly love.

In short, better permutations of this tale probably exist, but what’s here still suffices: A straightforward adventure mixed with a straightforward moral. No more, no less.

At least, for a change, there’s no wicked witch.--D

Episode 14 – The Spirit in the Bottle

Pitting wits with the devil…daring a demon with a wager…such devices and themes extend from biblical times, from The Book of Job to The Twilight Zone. And here, young Fredrick finds himself in a similar predicament—he releases a creature trapped in a jar only to discover he’s freed a demon. Rather than death, however, the devil bequeaths him with a magical cloth that can turn metal into solid silver. Imagining a life of luxury now for him and his father, he begins transmuting everything he can, accumulating instant riches and plenty of attention from the townsfolk smelling his wealth. But his father is less impressed, and warns his son that something cannot be had for nothing. A grim statement which will later prove true when the demon returns for what is due.

Well, sort of…

Although the moral here is self-evident, the story’s sloppy execution guts most of its power. Yes, young Fredrick has lucked into a lot of bucks and, not surprisingly, he overindulges soon after. But while his immature behavior is certainly not commendable, he never does anything so egregious—so outrageously terrible—as to make him deserving of an outright smiting. Consider: He never asks or makes a deal for the magic cloth; the demon gives it to him freely. So, with no contract signed or bargain made, why the demon should be owed anything is never made clear, just accepted.

Unless, of course, this is all a poor interpretation on this critic’s part. Indeed, the show’s denouement is so rushed, hamstrung, and poorly edited, the fate that actually befalls poor Fredrick, and why, is never properly revealed. A more poignant ending would have removed the demon completely from the ending while still giving it the final laugh--Frederick, to his horror, would learn that all the silver items he fashioned have returned to their original, worthless forms, meaning that he has some serious debts to repay. Now, with a lifetime of labor before him, Fredrick will understand what his father was trying to say.

But the true ending isn’t so elegant. It doesn’t even make sense despite striving to offer, apparently, its own kind of awkward irony.

An addled, unfinished script.--D

Episode 15 – The Iron Stove

As explained in an earlier review, an anthology series lives and dies by its variety and, more importantly, consistency of quality. Every episode is a unique “film” in itself, with different teams often assigned to each show. Different skills, styles, and techniques. Different visions. And here, in a story about anthropomorphic stoves, lewd talking frogs, and a vampy “fairy-imp” anxious to play the dominatrix, one can’t help but wonder about the creative soul who envisioned this particular tale…

Of course, clever dubbing helps temper the more pointed elements of the Western adaptation. But there’s still no hiding the desperate obsession—the wanton fixation—this particular demoness has for poor Prince William, a man she’s transformed into a literal walking and talking stove. And why has she done such an inexplicable thing? Although not specifically explained, it’s undoubtedly due to a previous rejection of her affections—a curse now only a true princess can reverse. And that princess, wandering lost in the forest, arrives soon enough. But, despite being willing to open the stove and set him free, the final step in his liberation—marriage—is a promise she’s not ready to give.

And this is where the English script gets dicey—the basis for the princess’ hesitation is laid on an early remark concerning her youth that's quickly forgotten...as she does offer her hand eventually. So, is she of age or not?

The Japanese cut handles the matter with more sense and finesse, blaming her reticence not on youth but a lack of familiarity—indeed, she doesn’t even know the man! Only when William sacrifices himself on her behalf does the princess have a change of heart. This dynamic, for whatever reason, was altered in the Western conversion.

Nevertheless, the core message remains the same for both—the power of true love is infinitely greater than mere infatuation. And for that, one almost pities the story’s villainess: Could a succubus ever appreciate real, unconditional and sacrificial love? Her rotten machinations clearly belie an unfortunate, lonely need; perhaps she has her own redemptive love story waiting to be told.

Incidentally, viewers should watch both language versions if possible. Each has its strengths. Each is endearing.

Each is incredibly weird.--D

Episode 16 – Bearskin

War. Whether won or lost, there are always soldiers cut adrift in the aftermath, delisted and tossed crassly back to a former life they no longer understand. It’s a problem today, and it was a problem, apparently, during the time this tale was composed; poor Johan, a war hero now left to vagabond status, travels the land penniless and, worse, without real purpose. An opportunistic devil seizes on his grief and makes him a sly deal—in exchange for riches, Johan must live like a beggar for seven years. He can’t bathe or pray (or die!) during this time, and must also wear the eponymous bearskin cloak the demon so “graciously” affords him. It’s a terrible wager that Johan nonetheless accepts. Anything is better than being a homeless veteran, it seems.

But Johan, despite looking despicable, has one advantage—his pockets already flow with the demon’s promised riches, allowing him to at least survive while otherwise despised. Hence, he drifts miserably for those seven years, occasionally using his hidden wealth to help the random soul. One of these individuals is a bankrupted merchant with whom Johan strikes his own kind of bargain; he’ll cover the man’s debts in exchange for one of his daughter’s hand in marriage. This saves the merchant but naturally mortifies his girls who want a beau, not a bear. Only the middle-child Christina, seeing past Johan’s ghastly appearance, agrees to the arrangement, becoming a veritable lady-in-waiting as her betrothed departs to complete his tribulation alone. Will he ever return? Or will tragedy end his earthly existence?

People love a good devil-gets-his-due story. Indeed, mankind has long yearned to become like the gods and, when the devil is involved, even outright trump these “superior” beings. Bearskin is no different, offering a likable, downtrodden hero who triumphs in the end, outlasting a crafty demon and winning a lovely maiden. It’s an irresistibly seductive story. Maybe, too seductive…

For what is to be learned from a fool who strikes an impossible bargain? Where Johan succeeds, most would fail. It’s advice viewers would best forget, a tantalizing flower not worth the poisonous prick.

As if the story itself were written, most deviously, by a devil.--D

Episode 17 – The Hare and the Hedgehog

Welcome to the most meta, multi-layered tale of the entire Grimms series—a story of doubled narrators, fables within fables, and enough morals to fill ten Sunday sermons.

The story opens with the usual narrator introducing “Old Samuel,” the resident storyteller of a small town. With a circle of kids listening intently, Samuel takes the narration reins with The Hare and the Hedgehog—a story about putting one’s strengths before his weaknesses, the advantages of mind over muscle, the wisdom of following one’s own advice, the importance of humility, and…and…yes, the story tries to say an awful lot. And all through a hedgehog who, after losing his temper with an arrogant hare, foolishly challenges him to a footrace. If he loses, the Hare gets his turnip patch; if he wins, he gets the Hare’s crop of cabbage. But, considering the hog’s stubby feet and tiny stature, losing seems all but guaranteed.

The premise is promising but thin, the sort of breezy morality tale normally tucked within the pages of a greater collection of parables. It’s perhaps no surprise, then, that the plot itself expands to include other stories, if only to pad its own commercial runtime. In one of these “micro-tales,” a crab uses trickery to outrace a fox. And in another, the famous Tortoise triumphs over the Hare in a similar competition. Both stories demonstrate that nothing is impossible, especially when wits are involved.

But as already illustrated, there is no singular moral connecting all these narrative threads; this is a tale of tales and a message of messages, a hodgepodge in which even the plot’s ultimate twist cribs from other sources. Remember The Wolf and the Fox? In that episode, there’s a scene where the rabbits outsmart the wolf by taking turns outracing him from burrow to burrow. Mr. Hedgehog, thanks to his clever wife, employs a similar scheme.

Even more peculiar--for all the helpful teachings on display, the story’s final and most overriding lesson is nothing if not dubious: Cheating is sometimes necessary. Or, arranged differently: The end justifies the means.

Is the story giving one permission, then, to cheat after making a foolish wager? Apparently, yes. And that’s exactly what the hedgehogs do to keep their patch…and take the Hare’s.

Nevertheless, for those who can overlook the mixed morals and just focus on the fun, this is an entertaining episode full of humorous characters and clever dialogue.

Just don’t use it for Sunday School.--D

Episode 18 – The Man of Iron

“The Man of Iron,” in this case, is literally a giant named Hans—the story opens as a cavalry of soldiers inexplicably pull this blue-skinned being from the depths of some unremarkable pond. Puny by comparison, these men only succeed with their capture due to a bolt of lightning that inexplicably strikes the titan unconscious. Incapacitated, he’s then carted away easily.

The story jumps next to the bratty Prince William; after being scolded by his mother for being decidedly unprincely, Williams trudges to the tower where Hans is being held. The giant plays on the boy’s pride shrewdly, tricking him into handing over the jailer keys. But once the being is freed and William realizes the punishment he’s in for, he asks Hans to take him along. The giant agrees.

Except…William remains a bratty companion who does nothing the titan asks. In order to instill the kid with some much-needed self-refection, Hans gives the boy a literal glimpse of his own soul; what he finds is a monster. Now seeing himself for what he is, the prince decides to give up his privileged past and live as a commoner. And it’s through this journey of struggle and hunger and humiliation that William, finally, becomes a real man. Becoming more, in a sense, like the giant.

On the surface, this is a sort of riches-to-rags-to-riches tale, a universal parable of taking responsibility and growing up—even if the script’s final events do unfold a bit too conveniently. In short, it’s a predictable but time-tested premise that sees a minor wrinkle in the giant himself, a title character who actually plays more the mentor here.

But that, perhaps, is also the tale’s true twist. Could Hans actually be, somehow, William’s “deceased” father? It’s an absurd notion that becomes more credible upon reflection. Consider: the King is “dead” (his absence mentioned only in passing); Hans himself is captured easily—too easily; the giant’s capture seems unjustified and serves little purpose beyond his later involvement with William; the Queen herself speaks highly of the being (?!), Hans somehow knows where the jailer keys are (under the Queen’s pillow!); despite William’s unlikable disposition, Hans takes an odd, almost fatherly interest in him; Hans later gives the boy command of his magical army; and finally, in the closing moments where William accepts his destiny, Hans says this…

“My son, you’re truly a prince, with a kingdom of your own and a strong, courageous heart.”

Maybe the hunky, strapping Hans is just speaking figuratively. Maybe he really is just the thirty-foot tall guardian of a tiny, non-descript pond. Or maybe, the Queen has her own tantalizing story.

Subtext, indeed, is everything.--D

Episode 19 - The Brave Little Tailor

Most probably know this tale from Disney’s 1938 animated short—here, Mickey smacks seven flies with a swatter, gets mistaken for a mighty seven-in-one-stroke giant killer, and is then tasked by the king to fell an actual giant. Through luck and some quick-footed ingenuity, the mouse succeeds—and all within the span of a seven-minute cartoon. It’s a classic for a reason.

This adaptation, of course, must stretch the proceedings closer to the half-hour mark, making for a decidedly less elegant refresh. Here, the tailor is so proud of his sudden fly-swatting superpower, he dons a sash that reads “seven-in-one” and then parades himself around town. Killing seven flies is impressive, but…marching pompously through the streets wearing one’s own reward? He certainly has the ego of a giant…

He eventually heads out into the country, and this is where the story’s theme and premise get a little confused—is the tailor a supernaturally-fast savant, an idiot-braggart deserving of a proper comeuppance, or a cocky trickster worthy of attention? The episode soon settles on the latter, with the tailor shrewdly defeating a pair of dragons, a furious unicorn, and a rampaging wild boar. He receives riches for these deeds, but never gains what he really needs: a little humility.

Any story of caliber requires a likable protagonist, but unlike the humble hero of Disney’s telling, the tailor here acts not with bravery, but with a smug bravado. One version grows its character into a true hero, the other a veritable scoundrel.

Is this a statement, then, on the power of marketing? Is the tailor’s self-aggrandizing sash more spell than fabric, a hypnotic net cast on both the public and wearer alike? A pretty but prickly charm that makes a self-important man important, but at the cost of his all-important moral soul?

Pity there can’t be a similar sash for modesty.--D

Episode 20 - The Wren and the Bear

Unlike previous episodes, the story here begins without any winsome narrator, nor does it conclude with any particular moral. It’s simply a silly comedy of errors about the pettiness of pride and that, perhaps, bigger doesn’t always mean better.

So, as “leader” of the forest, General Bear is accustomed to getting his way. And one day, he spies a wren chirping overhead. Learning that this wren is really the “King of the Fields,” he visits the bird’s home, surprised to find it little more than a hollowed out bush. Unimpressed, he shares his uncomplimentary thoughts with the three chicks nesting inside before retreating back to his cave. These three hatchings, however, are grossly offended by the interloper’s words, refusing to eat again until they receive a proper apology. And so King Wren flies to the Bear’s home and demands some proper respect. When the bear refuses…war is declared. It’s the four-legged versus the winged.

It’s a petty reason for a war, but maybe that’s the point in what otherwise seems an inconsequential tale. One can easily interpret these goofy creatures as human caricatures; it’s easy to laugh at the beasts’ pompous squabble, but is man really so different?

Anyhow, both sides soon clash in a mash-up more akin to a bar fight than a death battle. Thanks to having all of insect-kind on their side, however, the birds have the advantage in both numbers and sheer, surreptitious surveillance. In short, they take the win…maybe deservedly, but it lacks any sense of poetic or climactic satisfaction. King Wren won, but it was an engagement partly born of his own pride—a war he never should have waged in the first place. Neither side, really, was particularly “good.”

A forgettable tale, overall. It’s no wonder why the narrator sat this one out.--D

Episode 21 - Rumpelstiltskin

Most know the story of a girl forced to do the impossible—due to her father’s foolish boasting, the king now believes she can spin ordinary straw into spools of pure gold. Wanting to see this trick for himself, he locks the girl, named Gretchen here, in a room of unspun straw, demanding she produce the riches by morning. Now seemingly doomed, all she has is a desperate prayer. And lo, someone answers…

Not God, however, but a nymph—a mysterious little man who agrees to produce the gold in exchange for her necklace. And, when he’s beckoned again the next night, he does the same, taking her ring. The king is so pleased with Gretchen’s “work,” he asks her to spin once more; if she delivers the gold, he’ll make her Queen. But there’s a problem: with nothing left of value to offer the little spinner, Gretchen has no choice but to pledge her first-born child. A decision, of course, that will bear serious ramifications later.

Rumpelstiltskin has received many adaptations over the centuries, and this version is one of the more faithful tellings. The greatest changes are with the King and his increased importance in stopping the nymph. Indeed, once the imp returns to claim his prize, he reluctantly grants Gretchen one final chance to save her babe. If she can guess the man's true name within the next three days, he’ll dissolve their agreement. The king overhears this conversation and, after confronting Gretchen for the full story, hops dutifully to action.

Some versions of the tale suggest Gretchen keeps her deal with the nymph hidden, using only a trustworthy servant to deduce the man’s true identity. Here, the King orders his entire armed guard and country’s scholars to uncover any unusual name they can find, hoping that, by sheer numbers, they might recite the right one. Ram Bambina. Caspari. Peppinlock. Weasley Wig. The episode has its fun with the nonsensical guesses.

As expected, everything ends happily, but one wonders if the girl, back when she was but a maiden crying at her wheel, should have simply confessed the truth. Or rather, whether her father should have simply admitted the fib from the very beginning, thereby sparing his child the entire ordeal. The least honorable participant, however, is the king himself, who was clearly toying with Gretchen from the outset, playing the bully by virtue of his crown. A nobler fellow would understand that, sometimes, fathers forget themselves and tell tall tales. There’s no reason to get vindictive, especially towards the innocent daughter.

Lastly, why did the nymph get involved? The necklace and ring were but trinkets for a being capable of producing gold from nothing. Did he know, all along, this sequence of exchanges would lead the girl into giving up her child? If so, shouldn’t he have also foreseen his ultimate defeat? And more tantalizing still: Why would a nymph want a human baby? What did he plan on doing with it?

An unhappy ending for Gretchen, perhaps, would have led to a much more interesting story.

Episode 22 - The Water Nixie

Although a quality “children’s” show of its era, the Grimm’s series faced the problem of any anthology production—some stories are simply better than others. And through the show’s two-season run, a few episodes definitely meandered in their plotting, as if told by a desperate storyteller who’d forgotten half the script. Such is the case here.

The tale opens on a penniless miller who considers throwing himself into a nearby pond. He’s stopped, however, by the nixie, a beautiful fairy-like woman who even offers him a chest of riches if he’s willing to give up his first-born child. Foolishly or not, the man agrees.

Except, he soon reneges on the deal, spending the money while keeping his son, Shawn, far away from the nixie’s territory. And oddly, there’s never any consequence; Shawn grows up, marries a cute girl named Heidi, and is even there when his father passes away. “Stay away from the pond,” are the man’s final words. But, when hunting one night, Shawn does at last approach the nefarious water. And yep, the nixie finally claims her prize, dragging him down via a gross gaggle of monstrous, elastic hands.

The story then switches to Heidi as she cares for their newborn son. Now taking the hero’s role, she grows concerned and sets out to find her missing husband. Ultimately, she also gets snatched and dragged into the water, awakening in an underwater land where an inexplicable old woman is waiting nearby. She hands Heidi a golden comb with specific instructions; she must use it to continuously brush her hair at the pond’s edge, never letting it go until her husband is back safely onshore.

But it’s not so easy—the nixie attacks while she’s combing, and yes, Heidi drops the precious artifact. So the old woman gives her a golden spinning wheel to try again. And when that falls into the water, too, she then gives Heidi a flute (actually an ocarina) to play. And yes, when that also fails, Shawn and Heidi get trapped beneath the pond a second time.

It’s a weird comedy of errors that just keeps on spinning, the old woman always reappearing to grant another chance until the proper deus ex machina is finally found. It’s akin to someone reloading a visual novel until the right option is selected.

In short, Heidi and Shawn are eventually reunited, regaining their human forms after being turned into frogs (yes, frogs) and meeting again in a faraway land. They go on to live happily ever after, so it seems…except, didn’t they have a baby?

Guess the storyteller, beset by all those story strands and shreds, dropped that little detail right into the water.

Episode 23 - The Godfather of Death

The series, after a long and thoughtful run, concludes on a surprisingly dour note—one, ironically, that runs rather counter to the show’s opening theme…

“…and every story ends so happily.”

This episode definitely defies that starting promise, providing instead a tale as fittingly grim as its “Grimm’s” namesake might suggest to one unfamiliar with the series’ authors and pedigree.

The story opens with a sickly man cursing his life. Having just witnessed the birth of yet another son, he lacks both the wealth and health to feed his considerable family. So bitter is he, in fact, that when the actual Spirit of Justice descends to offer help, the man rebukes him. “There is no justice,” he declares. “The rich get richer, the poor get poorer.” Chagrined, the spirit leaves, stating he cannot help those who have no faith. Somewhat paradoxically, both are correct.

This gives another being, the Spirit of Nothingness (aka The Grim Reaper), an opportunity; appearing before the bitter soul, he offers to become the newborn’s godfather, ensuring the lad will thus live in abundance. The father agrees, offering his life in exchange despite the obvious dubiousness of the arrangement. Indeed, once the deal is struck, the Spirit even chuckles that he never said when he’d fulfill that promise.

A significant time-skip proves this true, as the next scene shows the son now grown, the sole survivor of a family no-more. It’s a dark revelation only made worse when the Spirit finally reappears. He wants the man, his “godson,” to play doctor to the sick, administering a magical herb to save the lives of some while withholding the same miracle cure from others. The Spirit, of course, decides who gets the magic treatment. The man agrees reluctantly, gladly saving the some but ruefully dooming the others. It makes him an accomplice, for good or ill—an actor complicit to the Spirit’s whims. But in the Reaper’s view, it’s simply a matter of balancing ledgers. Sooner or later, everyone passes.

Unlike the usual black/white proceedings of most fairy tales, this is a story built on moral ambiguity and suspect motivations, many of which extend beyond the scope of a children’s show. Indeed, if the Spirit seems more Devil than Death, maybe he is, using his “godson” not just as a convenience, but as a contrivance to stack the roster in his favor. Indeed, the being seems content on letting the “good” doctor save the ordinary and sinful while anxious to collect the young and successful, including a respected King and, later, his young princess; the man must withhold his ambrosia and let them both die despite knowing, in his heart, they deserve more time.

The ending, perhaps in keeping with the story’s ambiguous approach, is neither happy nor a complete tragedy. It’s more desperate, inevitable, and above all, bittersweet. Even the Spirit is left chagrined as the man makes his rightful sacrifice—a choice that costs him his life but, if justice does exist, saves his very soul.--D

That's it for Grimm's! But, we could do a similar Season One retrospective someday...let us know if this series is worth a second journey!