Teaching Tenchi: The Anime Everyone Loved, but now Nobody Knows

Anime is not a genre. And it definitely can’t be reduced to a singular definition.

Rather, it’s a collage…a collection of expression…a plethora of forms and themes and the human id released. It’s a creative template built for exaggerating, even breaking, the real world, reforming it into playgrounds of wish-fulfillment or horror. Indeed, some watch anime for the action. Some want the drama. And yes, some like innuendo, the sensuality—that stretchy sexiness so intrinsic to the medium and so immaculately matched to television screens. In many ways, anime is simply a romanticized reality, the idealized world for which humanity dreams but can never quite achieve.

But more than the thick hips, the giant robots, and the planet shattering ki blasts, there are the viewers themselves. The fans. The enthusiasts who were introduced to the medium through that one revelatory movie or TV show. For them, for us, anime as a whole is defined by that life-changing favorite, that one catch-all creation, that will now rest in our minds until the ends of time.

These seminal properties, of course, changed with the decades and varied by culture. Dial back to 1960s Japan, and it’s Astro Boy/Atomic Atom that captured imaginations and largely defined the medium. In the 1980s, it was big mecha’s turn to change the landscape—especially in the West where, after consuming years of The Smurfs or Scooby-Doo, kids were introduced to the virtues of “Japanimation” for the first time. These youngsters may not have understood that these relatively sophisticated, somewhat otherworldly, cinematic cartoons were the product of a different land, but they were nevertheless enthralled. They came to recognize the style, the fervor and the themes. And they wanted more. For them, Robotech and Voltron became their gateway anime.

The 1990s, however, was the true boon for the art form in Western circles, that decade where anime truly transcended its homegrown borders. Roger Ebert, the famed movie critic, applauded the theatrical release of Akira. Streamline Pictures, an up-and-coming media company, localized Vampire Hunter D, My Neighbor Totoro, and other popular Japanese films for Western consumption. Anime properties like Project A-ko began being adapted (and Americanized) into monthly comic book releases. VIZ Communications conned bookstores into carrying its volumed collections of Japanese manga (tankobon) by redubbing them as "graphic novels," a term that now carries universal sway. Nickelodeon imported kiddie shows like Noozles and Adventures of the Little Koala. And video games, a medium that had become indelibly linked to that land of the rising sun, now served as the perfect trojan horses for furrowing that anime aesthetic into young, ready minds—titles like Ys, Lunar, and Valis prepared unsuspecting audiences for the “big eyes, small mouth” revolution soon to follow.

And the art form itself, as least in part, continued to mature and generally improve. In Japan, Rumiko Takahashi’s Urusei Yatsura and Ranma ½ became cultural sensations, while Dragon Ball and Sailor Moon became world-wide phenomenons. Neon Genesis Evangelion mixed cryptic Christian mysticism with existential dread and, yes, giant robots. The fantasy motif branched into a variety of directions, from the romantic action seen in Escaflowne and Fushigi Yugi to the slapstick shenanigans of Slayers. And Pokemon combined the high-flying antics of its anime show with the video game of the same name, the former adding the humor and flash to the latter’s rote, turn-based action. For those who somehow missed Street Racer or Grimm's Fairy Tale Classics years before, they almost definitely noticed Nintendo’s cock fighter-turned-Pocket Monster sensation.

In short, the anime hits kept coming. And the art form, finally, began achieving a measure of western prominence as it moved incrementally towards outright global dominance. Dragon Ball, Pokemon, and Sailor Moon were the early heralds of this new dawn—a renaissance of exuberance, flourish, and kitsch reaching far beyond conventional American or European animation. But Japanime’s niche beginnings and its gradual transformation into the media empire so recognized today is a story that often excludes an important chapter. Or rather, a certain property. Far beyond the romantic slice-of-life antics of, say, Ah! My Goddess or the more action-oriented YuYu Hakusho, this work combined all of the category’s best elements to form a singular, seminal, and universally-loved work of art. A franchise, in fact, that expands across multiple mediums, that spans multiple canons and, for a time, was all the talk across magazines and the surrounding fandom. For an entire generation of anime-enthusiasts, especially those of a gaijin persuasion, this was the default, most baseline expression of Japanese animation, the best catch-all example of that exciting, if sometimes confounding, media movement slowly rowing into western lands.

Tenchi Muyo! was (and is) everything an anime needed to be. It had action, romance, humor, and plumes of sensual fervor. Pretty girls, cute critters, giant spaceships, and sinister villains…all coupled by sublime art and a musical score of affirming mirth. But most important, it had heart. It was a fairy tale for the modern age.

It’s about a boy, after all, who soon finds himself at the center of an epic secret—one that spans galaxies and generations, one of space pirates and alien princesses and heinous, sneering villains. The boy’s simple life is but the prelude to a greater story, the pretext for a destiny that can’t be stopped, only confronted in grandiose, epic style.

So, welcome to Tenchi Muyo!, a tale of careening fates, of loneliness and love, of growing up, of forgiveness and peace and, yes, plenty of comedy and sexy scenes. Welcome to the blend of theme and genre that not only defined anime in the 1990s, but would raise the form to greater prominence and performance as the 21st century emerged. Tenchi Muyo! was the singular creation that offered it all—every genre squished into one—anime’s greatest gifts woven into a quintessential, seminal whole. In a sense, Tenchi Muyo! defined anime, made it great, and, in a sense, made it American.

And yet, just a mere generation later, the show is barely remembered. Barely recognized. Snubbed by a viewership clueless to its existence, and forsaken by an industry happy to leave the Tenchi franchise entirely, thanklessly behind.

Anime's Slow Trek to the West: How Tenchi Redeemed the Entire Industry

The East's A-ko...

...or the West's Scoob.

Whom would you choose?

Despite its simplistic pretensions, the Tenchi canon cannot be easily defined by a few stock phrases or descriptive tags; terms such as “magical girl” or “martial arts fighting” might properly describe shows like Sailor Moon or Dragon Ball Z, but Tenchi Muyo! has always transcended such narrow definition. It’s a modern fable, in essence…a coming-of-age story that sees the young Tenchi Masaki slowly deciphering his heroic destiny amidst a cast of exotic characters and encroaching, cosmic foes. Beautiful alien maidens, inexplicable evils, and some tests of true courage all await a boy more peasant than prince, more farmhand than commander—just a confused high school student served a big plateful of Fate. Indeed, beyond being the chief protagonist, Tenchi serves as the audience’s avatar, the two forming a symbiosis of surprise and incredulity while still diverging in their ultimate hopes and desires. Tenchi, perhaps ironically, wants a normal, quiet life…while the watcher probably fancies quite the opposite. What man wouldn’t mind a few of Tenchi’s “curses”—to be the lucky recipient of power and adoration untold? No question, Tenchi Muyo! is pure wish-fulfillment combined with the age-old Hero Myth told a thousand times before with a thousand different names, a thousand different faces. Tenchi is the stand-in man for any would-be hero hoping to stake his claim into the world…and better still, a grateful girl.

And yet, that heady summation is itself a gross oversimplification of what’s become its own mythology. First billed as Tenchi Muyo! Ryo-Ohki in 1992 Japan, the saga began as a series of six individually-released, direct-to-video episodes, or OVAs. Together, they tell the first arc—the first adventure—of Tenchi’s self-discovery and the interstellar ladies that come, as if drawn by a tractor beam, to dock within his home. In Tenchi, they sense the essence of greatness…a great Fate awakening. And thus, they want him.

It was the perfect setup—a serendipitous mixture of battle and romance and catty wackiness that won an instant fandom. Everyone wanted more Tenchi Muyo…and really, more of those pretty girls…but there just wasn’t enough content to satisfy demand. The direct-to-video approach was too slow—too incremental in its individual releases—to properly capitalize on what was becoming a serious phenomenon.

And so, a similar TV show was devised…along with video games and radio dramas and novels and manga and animated spin-offs. The unassuming fairy tale had suddenly exploded into a media and merchandising sensation, a self-perpetuating empire of competing continuities and retellings all contradicting and cannibalizing the other.

And obscuring, even further, the original, already convoluted lore.

It was a mess—still is a mess—that probably polluted the property to the point of its eventual demise years later. But in those heady 1994-ish days, fans had an insatiable need for more Tenchi, ravenously sucking up whatever stuff, glut, and smut than they could find to further celebrate the now unbridled franchise. And eventually, as the anime medium itself began gaining more weight in the West, Pioneer Entertainment saw an opportunity. From humor to drama to its awesome action scenes, the Tenchi Muyo! series had everything, and had certainly won the hearts of the Japanese public. Might not the series cast a similar spell in America? So, Pioneer got to work, investing significant energies into an English-speaking voice cast equal to the original talent, plus redubbing all the original songs with Western artists capable of retaining the spirit and fervor of the original performances…all along with, especially for the time, an excellent localization. And happily, the company’s efforts were wildly successful.

Although not quite the phenomenon it was in Japan, Pioneer did the unthinkable in that mid/late '90s frame—it not only made Tenchi recognizable in a Western World still largely adverse to the art form, but it made the series the dead-on staple, the preeminent example, of Japanese animation in its entirety. More than Dragon Ball or Sailor Moon, Tenchi offered the breadth, the variety, and the accessibility to those who still only vaguely understood, or tolerated, those odd Japanese cartoons. Soon, Tenchi DVDs could be bought in Wal-Marts and Targets. Bookstores, on their one or two shelves relegated to manga at the time, proudly brandished the Tenchi graphic novels. American teams were gathered to make new Tenchi comics and other content. Dolls, statues, plushies, and collectible cards were all released to grateful fans. The Cartoon Network even hosted the show on its anime-themed Toonami block of programming, gaining it serious mainstream attention. Finally, anime had its connective bridge between East and West—that seminal example of what makes Japanese animation special, and why it was worthy to be watched next to the likes of Looney Tunes, The Simpsons, or The Little Mermaid.

But again, for all Tenchi Muyo! did to both showcase and popularize the medium, it quickly became displaced as other properties flooded the market. Netflix, Crunchyroll, and other sources offered their own animated content by the deluge, burying the series like an ancient YouTube video. And without offering anything particularly new or dynamic itself, the franchise became but the wistful reverie of a different time.

Yes, anime is bigger than ever before. But Tenchi Muyo!, for all that it was...for all that it is...for all it accomplished…

Has never been smaller.

What is Tenchi Muyo!?

Do people dictate Fate, or does Fate develop people? For the unassuming Tenchi, it seems the latter.

Tenchi claims his sword...and then the women take it, too.

Simple boy...

Super sword...

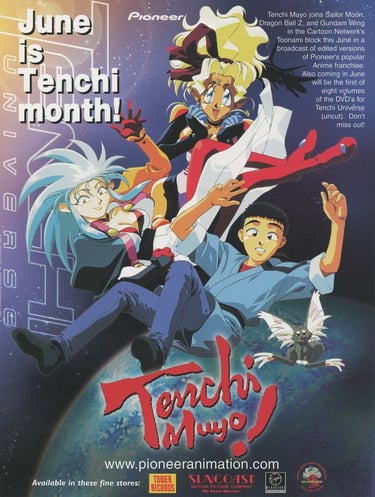

Tenchi Month? Incredibly, the Tenchi Muyo! franchise was once so popular, advertisements like this could be made...and taken quite seriously.

Robotech (Macross) was huge amongst kids in the '80s. They didn't know it came from Japan, and yet, somehow they sorta did.

From Top Left Down: Akira, Adventures of the Little Koala, Ys 1, and Valis 3. The latter two are video games with that distinct "Japanese" look.

Dragon Ball (top) and Sailor Moon (bottom), like Tenchi, were key players in the West's '90s anime boom. But their reach was limited by their ambitions: tough guys and pretty girls saving the world. The Tenchi franchise cannot be so easily defined.

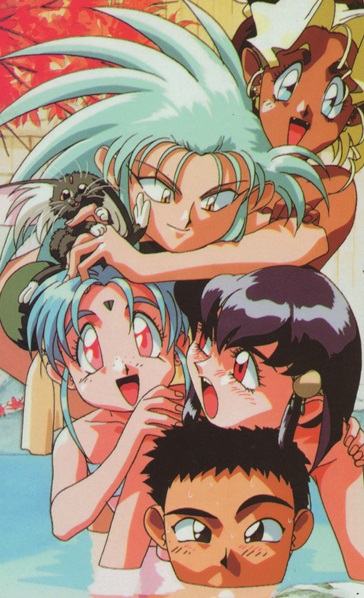

Tenchi Muyo's eclectic cast of characters is practically unparalleled. And more than pretty faces, more than exaggerated drawings...they feel real, both endearing and enduring.

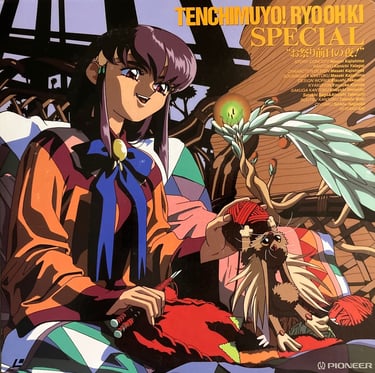

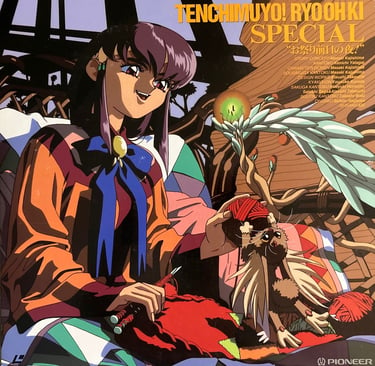

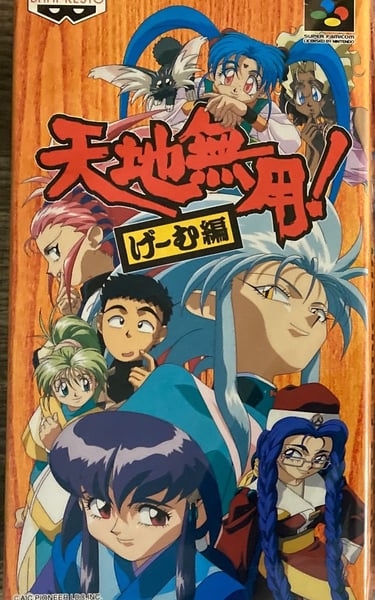

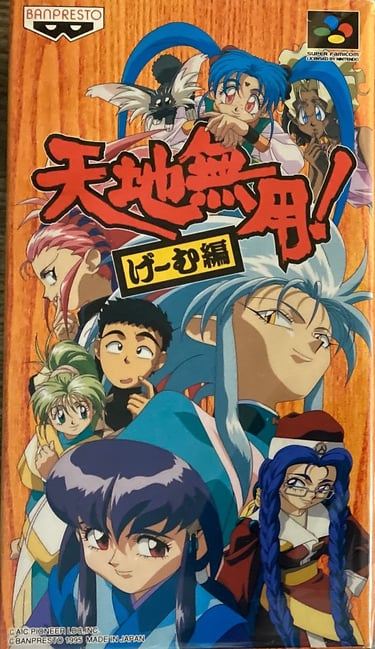

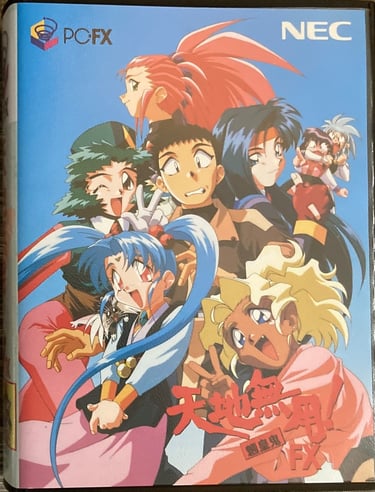

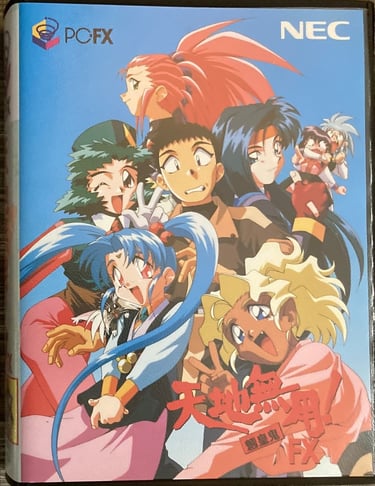

Tenchi Muyo! merchandise was monumental in its day, including laserdics (on top) and video games (below).

This feature is meant to both evaluate and celebrate a property that, by all reckoning, should still be around. Should still be on everyone’s Top Ten lists. Should still be enjoying new stories, new comics, new games…should still be the talk in forums, should still be plastering its beloved characters like Ryoko and Ayeka over magazines and postcards and iPad screens, should still be represented across toys and statues and gatchapon toys.

Yes, this is an examination of everything Tenchi, from continuity comparisons to vintage merchandise to the droves of alternate media that exist for the property…even if most of that swag is from twenty years ago. Moreover, the lore will be considered, the competing series judged and ranked, the individual shows and episodes summarized, praised, and criticized...depending on the case.

But most of all, this will be a guide for everyone—for those unfamiliar with the franchise, for those baffled by its disappearance. For those old-timers anxious to remember the show’s golden days, and those newbies happy to be educated in just what made Tenchi and his gang so great. This feature, like a Juraian Tree (more on this later!), will branch and fork until almost every critical story beat is referenced…within reason. Not everything can be covered, as dozens of untranslated Tenchi novels and doujinshi certainly attest. But as an in-depth introduction and homage to the spectacle, the miracle, the marvel that is the Tenchi family…

…this, by the Grace of the Three, will hopefully suffice.

In Need of Tenchi

A soiree of tantalizing girls.

Here's saluting one of anime's most important, imaginative series.

Contact: lostnostalgiaproductions@gmail.com

Website: www.lostnostalgia.com

Like what we're doing? Please consider throwing us a dollar into our Patreon page's tip jar!