Still the Beaver

- And Still a Boy

A Somber Review of the Beaver's Not-Quite Glorious Return

The film opens with a wistful montage of old family photos along with the series' theme, now played with a simple melancholic plucking of strings. It sets the tone for a more dramatic, less comedic portrayal of the Beaver clan.

Most TV shows, no matter how good, carry a strain of kitsch disposability. They air, they age, and they fade away. The luckier programs get an extension through syndication, kept alive through “reruns” for maybe another decade. But ultimately, even the most popular series become displaced and forgotten, reduced to curiosities of a past, inscrutable age.

It’s ironic then that the situational comedy (the sitcom), often considered to be the lowest form of production art, is the genre best apt to resist such pop cultural indifference. Although most sitcoms are doomed to obscurity the moment their last episode airs, a few always defy their times, transcending popular trends and contemporary opinion to become classics—shows still remembered, still loved, still watched no matter how many years have passed.

The Andy Griffith Show. I Love Lucy. The Dick Van Dike Show. The Munsters. I Dream of Jeannie. Sometimes, against all seeming reason, a show will emerge that never quite goes away. A show that, in cases like The Brady Bunch, was never particularly successful even during its initial run. A show that bears an almost mystical quality, an enviable immunity to the future. Even programs designed with disposability in mind—ephemeral productions meant to fill a time slot, to be “run and done”—sometimes achieve this immortality. Saved by the Bell might be the most obvious of these juggernauts; despite its now dated pretensions, the show endures from generation to generation.

And sometimes, these unstoppable sitcoms get rewarded with a sequel or spin-off. Andy Griffith got Mayberry R.F.D. Cheers was followed by Frasier. More recently, The Big Bang Theory got Young Sheldon. But these continuations aren’t always successful. Aren’t always good. And such is the case with one of the greatest shows ever made, one adored yet notorious—the venerable Leave It to Beaver. It's adored for being an excellent slice of 1950s suburban Americana. But notorious for spawning a certain dicey 1983 revival known as…

Fans of the original series know the Cleavers, that happy homestead representing the idyllic nuclear family. Ward is the dedicated, wise, attentive father. June is the sweet, caring, devoted wife. Wally is the good-natured older brother. And Theodore “Beaver” Cleaver is the well-meaning younger sibling who has a penchant for getting himself into a variety of predicaments. A circle of colorful friends and acquaintances fill out the surrounding cast, creating a town—certainly a street—that still feels real even today, despite the black-and-white and prim-and-proper trappings.

Not so with the follow-up, however. Twenty years after the original’s cancellation, audiences were apparently eager for more Beaver; Still the Beaver aired as a CBS Saturday special that saw the eponymous scamp revamped into a grown man…sort of. Not exactly mature, not exactly manly, he was now an adult saddled with two sons and an unhappy wife. So unhappy, in fact, the movie opens with her getting him fired from his job (he worked for her father) and then ousting him from the house. The Dragon wants a divorce, and in typical Beaver fashion, the would-be hubby chitters and gnaws and then acquiesces, not even “allowed” to take one of the two family cars as he retreats back to Mother in his hometown of Mayfield. Yep, he takes the bus.

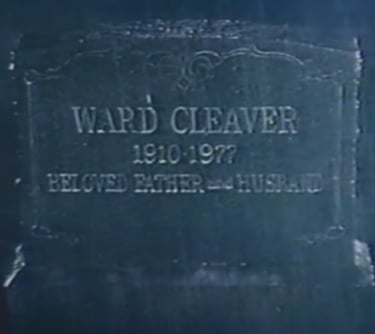

It’s a rather sour beginning for a franchise so synonymous for its happy-go-lucky qualities. And as Beaver meanders and mopes at his old home, clueless as usual, neither Wally nor June seems to know what to do, either. June frets about her son while visiting her husband’s grave (Ward has since passed away) while Wally can only roll his eyes at whom he sees as his hopeless little brother.

Ward's absence is the real problem. He was the key to Beaver’s growth and maturity, and the crucial component that made the original show both functional and resonant. The force, in short, that gave each episode its direction and purpose. Beaver was cute and funny, but without Ward and his guiding wisdom, there was no payoff. No point. Just a dumb, bumbling kid.

And here, viewers get to witness that Ward-less world, and in effect, an especially witless Beaver—a person without agency, a spine, or considerable will of his own. He still hasn’t quite grown up. Still hasn’t gained enough ambition or grit. He’s still literally The Beaver; still a kid, but now trapped in the pudgy body of a wondering, wandering man. And though his wife seems snide and icy, by the movie’s end, one can almost sympathize with her seemingly vindictive decision. She needed a man but married a boy.

None of this is helped by actor Jerry Mathers, whose portrayal of Beaver is listless at best, unseemly at worst, as if he was channeling his younger self’s pubescent ghost. “Beaver,” as a concept, works only in a kid’s dimensions; the same childish charm can’t quite carry a middle-aged man. When Beaver gains custody of his kids, finally bringing the film some semblance of a plot, he finds himself with two boys who regard him much like their mother does—as a man still trapped in his cozy, rosy past. In some ways, the kids are more “grown up” than he is.

Still the Beaver is mercifully short at just under ninety minutes, but the story would soon be continued over a four-season sitcom sometimes redubbed The New Leave It to Beaver. The series mirrors the movie while oddly contradicting it: Wally is now Beaver’s next-door neighbor, and instead of having a newborn son named Ward (as the movie depicts), he’s given a precocious school-age daughter instead. But more generally, the production simply fails to recapture the authenticity—that genuine guilelessness—that so defined the original series. And yet, it also drops the heavier, more existential pretensions that so diminished the TV movie. Beaver is less the star and more an equal participant this time, sharing his space with the greater cast. Having less Beaver, it seems, is for the better.

Nevertheless, both versions of Still the Beaver—the film and the sitcom—have long been lost to the draughts of time, being almost impossible to find circa early 2024. YouTube might be the best repository for the series, thanks to those who dutifully recorded the show on Beta/VHS cassettes back in the day and have since uploaded their treasures to the network. It’s not the greatest way to watch, but currently, it might be the easiest (and only?) option. Not that it probably matters to the average fan; a few episodes will likely be enough to satisfy those of just passing curiosity. It’s a reunion show, after all, not a resurrection…none of the new 101 episodes can match the simple brilliance of the '50s classic.

And for the time-deprived, the original TV movie suffices nicely. Flawed and aimless as it is, it does serve as a fitting tribute to both the character of Ward Cleaver and his actor, Hugh Beaumont. As an homage to him, and perhaps fatherhood in general, the film does achieve a certain poignancy—a quality the TV series never quite clenches.

A good father, it seems, does make all the difference.--D

The movie is at its strongest when flashing back to Ward, who has since passed. And yet, not to be outdone, his spirit still hovers over the entire picture, granting the film both a nostalgic and sobering quality. In many ways, the story is more a fond farewell to him than a hearty reunion with the others.

Beaver, for better or worse, is largely the same, and carries most of the film's existential weight. Wally, predictably, is the more successful and confident one; his one struggle concerns his difficulty siring a child with wife, Mary Ellen.

Much of the extended cast from the original series comes back. Eddie (bottom left) is the same Eddie. Larry (upper left) is...not the same Larry.

The movie remains vague as to why Kimberly, Beaver's wife, finally demands a divorce. His kids, however, offer a clue--like their mother, they have no idea what to do with him.

Although not originally planned, Still the Beaver eventually became a TV series lasting an astounding 101 episodes. Also known as The New Leave it to Beaver, it's okay for what it is but lacks the timeless relatability that made the original so special.

The new series is definitely a bit more "progressive" than the original. Here, in the show's final episode, Beaver receives a bachelor party and finds himself staring through the legs of a stripper. Still the Beaver, indeed.

The sitcom, although supposedly a continuation of the original movie, seems to exist in its own dimension. The most obvious difference comes in the form of Kelly, Wally's only child. Per the film, the "daughter" should have been a newborn son named Ward (in what was a touching nod to the Cleaver patriarch). All that's tossed here.

Contact: lostnostalgiaproductions@gmail.com

Website: www.lostnostalgia.com

Like what we're doing? Please consider throwing us a dollar into our Patreon page's tip jar!