The Great Brain - Review

The Great Brain

Author: John D. Fitzgerald

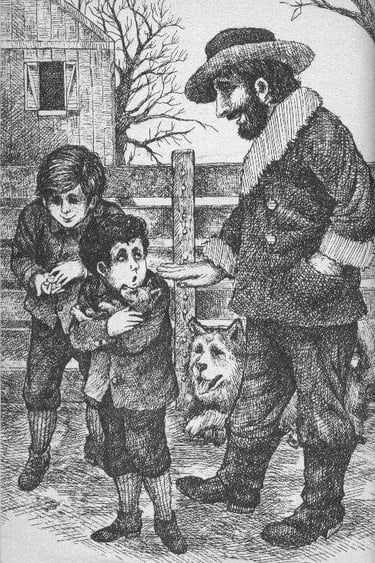

The Great Brain is actually a series of eight books. The editions are usually punctuated with the occasional illustration to help set the context for a bygone age now a little difficult to imagine.

Written in 1969, The Great Brain seems a doubly-strange anachronism in the modern marketplace of children’s fiction. Far from the magical schools and junior high farces that fill bookshelves today, it’s a sometimes raw, sometimes odd period piece based (loosely?) on the author’s childhood in late-19th century Utah. Indeed, his was a land of Mormons and Catholics, not magic. A time when kids played games like “Jackass Leapfrog” and “Duck on the Rock,” not Fortnite or D&D. An era when completing the sixth grade was, for many, the rite of passage to adulthood.

The story is also unusual in that, although told through the immature eyes of young J.D. (John Dennis), it’s really about his older brother Tom, aka “The Great Brain.” Tom is many things, from schemer to swindler to entrepreneur, but above all the ten-year-old is a quick study able to outsmart even the sharpest adults. Each chapter is essentially a short story recounting another of Tom’s schemes or exploits; he’s undeniably a selfish opportunist, but one whose deeds usually do benefit his friends and community. In some sense, then, Tom’s a prototypical Objectivist.

Although appropriately rose-tinted, the book doesn’t flinch from the grim realities and general grittiness of its era—this is a world of passive, if unintended, anti-Semitism, a world where a nail through the foot could mean amputation, a world where the only cure for xenophobia is literally fist-fighting every ignoramus in town. It’s this matter-of-fact honesty, mixed with the optimism of a young nation’s golden age, that grants the story a vaguely patriotic and hopeful fervor. It doesn’t pander. It doesn’t apologize. It doesn’t lie. But circa 1896, the future was coming fast and looking increasingly bright. In short, the optimism was justified.

This authenticity does come juxtaposed, however, with a few developments that feel decidedly less genuine. The amputee mentioned earlier? J.D. agrees (eagerly) to help him commit suicide, attempting both a drowning and a hanging before Tom intervenes. Is this supposed to be an amusing bit of fiction, or is this a real anecdote the author expects his readers to take seriously? What’s more, in a different chapter, J.D. intentionally infects himself with the mumps so, once recovered, he can then tease his still-bedridden brothers. J.D. is only eight years old, but…what kind of sociopath would do that?

Fortunately, these inexplicable blots don’t mar an otherwise fun, intriguing peek into a bygone stage of American life. Whether Tom’s great brain can lure the modern kid into his world of hand-cranked ice cream, water closets, and horse-drawn emporiums is the real question.

And tragedy.

For Tom’s story, if not completely relatable, is at least real—a reverie born of real human experience. No number of magic hats or talking cats can match the true grit of history.--D

Thanks to greatbrain.weebly.com for the illustration.

Contact: lostnostalgiaproductions@gmail.com

Website: www.lostnostalgia.com

Like what we're doing? Please consider throwing us a dollar into our Patreon page's tip jar!