The StoryTeller

Original Airdate: 1987-1989

The Fantasy.

Once the province of cartoons, video games, and the bookshelf, it’s now everywhere: TV shows and movies now commonly dabble with the fantastic, providing the shiny, romanticized lives so many wish could define their own existence. Anime is another huge contributor, perpetuating the sunny possibilities that realms of magic and colorful characters and endless adventure would naturally engender. Beautiful clothes and sweeping hair and perfect smiles mark these escapist jaunts with nary a hint of grime or unseemly stench. From Harry Potter to Pokemon, fantasy has become, more than ever before, an escape from reality rather than a reflection thereof.

But not in the ‘80s. Fantasy then was a grim and grittier sort, blending its splendor with a decidedly dirtier sensibility. The Last Unicorn’s titular character was a creature of grace and elegance juxtaposed against a gnarled, withered world. The NeverEnding Story counterbalanced the joys of boundless flight and heavenly skies with a ravenous, horse-swallowing swamp slurping below. This was not a decade of idealized forays into the unknown, but of magic mixed with the tragic…of glorious pearls tossed into a thicket of thorns. These dimensional trips were not always dreams fulfilled, but horror instilled. They were worlds of reward, but also mourning.

Enter Jim Henson. Master puppeteer and father of The Muppets, he could make the nonsensical possible. Imbue a sock with a soul. Bring flesh to felt. And thus, he was the natural agent to elevate the entire genre to a higher form. Give “Fantasy” the friendlier coat and color it had often lacked before.

But did he? Though his films The Dark Crystal (1982) and Labyrinth (1986) do bear his quirk and idiosyncratic whimsy, these aren’t happy frolics through Sesame Street, but haunting jaunts into the creator’s deeper, darker imagination—places to witness but not necessarily visit. Indeed, Crystal’s sickly villains absorb their captives’ life force with enough gruesome glee to make a gargoyle squirm. And Labyrinth’s creepy Goblin King is a barely-veiled substitute for the devil himself. Henson’s brand of fantasy did less to allure and more to subvert, essentially becoming cautionary warnings; the point wasn’t to seduce, but to discourage. Anyone yearning to leave their boring world and existence for something “better” would soon rethink such foolishness. The intent was not to provide a vacation into Wonderland, but offer a grateful escape back out. Henson, whether intentional or not, shared the same message of his contemporaries: Reality, for all its faults, was secretly superior. The mundane, if lacking magic, was at least comfortable, predictable, and safe.

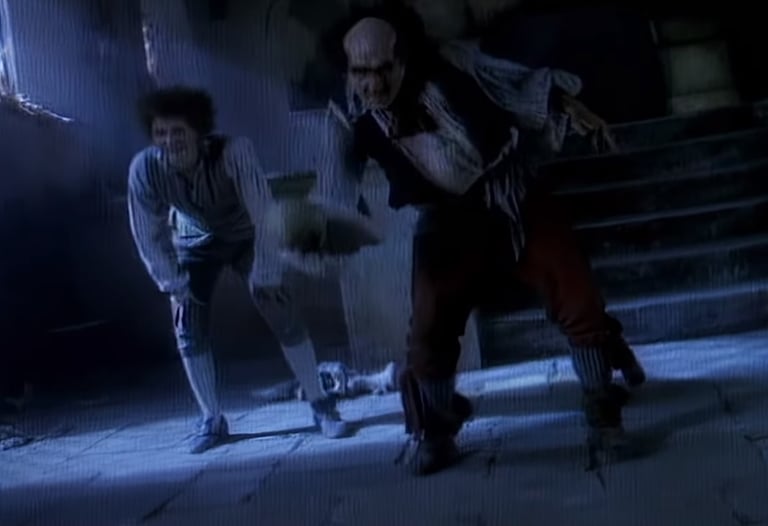

Unconsciously, it’s a powerful lesson. But audiences don’t want a fantasy gilded in grime, a golden apple hiding a backside of bruises. They want an escape into, not from, the world they’re watching. And so, perhaps unsurprisingly, neither film was a huge success for the hopeful auteur. Problem was, Henson never took the hint, trying yet again…but for the smaller screen. The result was The StoryTeller, a series that retold obscure fables dredged from ancient folklore. In the U.S., these half-hour fire-sides—nine in all—were broadcast as a mix of TV specials and spots on the short-lived The Jim Henson Hour. Like their cinematic counterparts, each episode utilized cutting-edge advancements in puppet wizardry to tell their tall tales. And also like their big-screen brethren, they sport the same oily, rough-spun aesthetic that helps make their worlds feel both real but unseemly—accurate, perhaps, to their time and setting, but not at all enticing to those expecting Kiki’s Delivery Service or World of Warcraft. Indeed, viewers can almost see the fleas and lice hanging in the characters’ clothes and breathe in the stank offered from their unwashed bodies. Again, this is fantasy reflecting, not idealizing, reality.

Unlike the Muppets, Fraggles, and Big Bird, Henson’s would-be classic has largely faded from memory in ages hence. The show benefits, at least, from good acting and a collection of sordid, off-kilter stories rarely told anywhere else. But the aforementioned grim and grime, coupled by some dated special effects and oddly low-budget sets make each episode feel even more surreal now than in their late-80s debut. The absence of a proper HD remaster exacerbates the problem further; stranded on an ancient 2003 DVD release, the episodes are often a mud of browns and grays on modern TVs.

Despite those drawbacks, The StoryTeller stands as a dynamic demonstration of a man’s driven ambition—a showcase in how true talent cannot be properly copied by any successor or would-be interloper. The show might have favored the gritty over the pretty, but in the long run, its ratty garments now hang proudly beside the clothes of a more commercial, homogenized show. It’s a nine-part testament to a man who could turn a thought into life, of a man who passed too early, too soon before his rightful time.

The StoryTeller collects the stories once sung by masterful poets and bards, then rethinks and resings them courtesy of the greatest bard of them all. Watch them with respect…and some rueful regret.--D

The NeverEnding Story is characteristic of its time and genre: no bright colors or upbeat themes allowed.

Labyrinth is Henson's other "darkish" picture, what with its somber tones and somewhat disturbing premise. Compared to Crystal, however, it packs more depth and texture.

The Dark Crystal's grim and earthy tones were a huge departure from Henson's frollicky, whimsical Muppets, but not so much from other fantasy films of the era.

The StoryTeller prevailed for nine episodes before disappearing from the airwaves. Each of the tales is conveyed by the eponymous storyteller and his hapless mutt shown above; they're the only persistent fixtures between the different narratives.

The StoryTeller: Greek Myths served as a sequel series of sorts to the original. Aired in 1991, it lasted four episodes.

Hans My Hedgehog is a story of horrors. A mother, unable to bear a child, makes an innocent wish that sees her suddenly, miraculously pregnant. But when the babe is born, it’s no human child, but an inexplicable, anthropomorphic Hedgehog. How is this possible? Where does the child come from? Neither question is raised, let alone explained in what is essentially a subversive, virgin birth. It’s the kind of tale that could have only been birthed in a very different time and ancient place.

Not surprisingly, Dad’s not too keen on the tyke, and once “Hans” becomes an adult—into a full, man-sized creature of quills—he leaves his family’s homestead for a lonely abode far, far away. Years later, a lost and bedraggled king knocks on his door, begging for shelter and mercy. And Hans, seeing an opportunity, makes a deal—in exchange for seeing the king safely home, he gets to marry whoever runs out to greet the beloved ruler first. And much to the King’s chagrin, that lucky winner is his daughter.

The story gets only weirder; although Hans is as sophisticated as any man, he eats like a pig, revolting the palace royals and his would-be mother-in-law. Only the Princess, who does marry him dutifully, knows there’s another side to the creature; at night, a human man emerges from that gross coat of quills. If she can keep a certain promise, the hedgehog will be banished, and the handsome man hers forevermore.

If nothing else, Hans My Hedgehog reveals how easily—how viscerally and primally—humanity rejects anything different from itself. How easily Man judges something to be ugly. Viewers will doubtlessly squirm when they find themselves sympathizing with the farmer or the King or the poor Princess; the audience is supposed to be rooting for the hedgehog, but damn, he’s just so gross!

But more generally, the story is a collection of nonsense, good for passing the time at a camp-side fire but hardly a classic by itself. The tale’s dour cinematography doesn’t engender any lasting love, either, but that’s typical for the sepia-ridden series. In the end, the episode’s likability comes down to a simple, uncomfortable question—could you, the viewer, ever love a gigantic, gnashing hedgehog?--D

There's my big, beautiful boy...

The King and Hog strike a deal.

The Princess is the real deal--devoted to her duty.

Eating with Prince Charming...

The man finally emerges from the hog...although what the weird wings are all about is never noted or explained.

Hans My Hedgehog

Fearnot concerns a simple lad with a simple wish: He simply wants to “shudder.” In other words, he wants to experience true fear, an emotion he has never encountered. And so, with both his father’s approval and pouch of coin, he ventures out into the unknown to procure the perfect scare. He befriends a dubious vagabond on the way who, after hearing the boy’s story, and in exchange for the pouch, agrees to run him through a circuit of fearsome dangers. A hypnotic, underwater monster. A hunchback who robs men of their bottom torsos. But ultimately, it’s not the ghouls who grant the kid his lesson in fear—it’s the threat of losing the one he most loves.

The story, taken from an old Germanic folk tale, feels more akin to the schlock one would find on a late-night, syndicated anthology show. It’s imaginative and even fittingly ghastly when appropriate, but it lacks a greater vision—a moral center—that define the greatest fables of antiquity. Fearnot—literally the protagonist’s name—simply sails his way through one danger after another without suspense or consequence. It’s only when he’s back home and gazing upon his lady love that he learns anything…making the rest of the adventure feel strangely incidental.

His triumphs are also ham-fisted. When he defeats the hunchback in a game of tiddlywinks, he does via a carving machine he just so happens to take with him. As the villain watches, the hero shaves the skull they’ve been rolling into a cleaner sphere, then rolls it for certain victory. Clever? Or just convenient?

But Fearnot’s greatest flaw is the lack of a greater message or scandalous twist. The best fables have something to teach or say; Fearnot merely entertains in its arbitrary way. Which makes it another fitting fireside tale, but like wood into ash, it’s nothing that lasts.--D

Dad wants his buttons, but Fearnot forgot.

Fearnot joins forces with a dubious vagabond. Not life advice, this fable be...

This is what a Wurdle looks like.

Tiddlywinks with a hunchback...not quite beer pong at a frat party.

Fearnot's lady love is the impetus of his first, climactic shudder.

Fearnot

A Story Short poses and interesting question: What if a storyteller—a person who makes a living weaving and telling tales—suddenly ran out of ideas? Such is the case here, with the series’ storied narrator, the Storyteller, also participating as the episode’s hapless hero.

The episode puts the codger into quite the conundrum: he must either regale his king with a new story each night for an entire year, or face execution. He performs well until, on the 365th day, the old man awakens to a nightmare; he can’t think of a final tale. His loom, inexplicably, has skipped that last life-saving stitch.

Fans of Arabian Nights might detect a slight similarity between the two myths, the former also featuring a storyteller, this time a woman, offering stories in exchange for her own life. But in A Story Short, the Storyteller fails—at least seemingly—after losing a wager to a travelling beggar and being transformed into a miserable flea. Now helpless, the old man can only watch as the trickster continues his mischief throughout the royal castle, ultimately targeting the king’s young son. No one’s safe in what’s becoming a senseless tragedy.

And that, ironically, is the twist; the Storyteller now has his story. Can he save himself after all?

As with Hans My Hedgehog and Fearnot, this is not a “pretty” fable. The grime and gray of the previous episodes are retained here; it’s the same greasy, dusty, flea-bitten world without a spot of color in sight. But unlike the earlier excursions, there’s a greater sense of whimsy here—a vague sense of winking humor to soften the outlandish spectacle and the borderline nihilism of a reality lacking proper rules. The tale still has some upsetting, unsettling moments, but there’s an almost cartoony (muppet-esque?) sensibility to help counterbalance the top-heavy horror.

A Story Short, in short, is the rare episode with some hint of continuity. It upgrades the Storyteller from somber stranger to an individual with a certain history and context. A certain sympathy. Somebody not unlike his audience.

And thus, this is the story that grants the overall show its much needed soul.--D

The Storyteller cons his way into the Royal Kitchen with his famous "stone soup." Note the beggar on the right.

The old teller of tales, now deemed a trickster, is brought before the king for punishment. Rather, he's given a job--Court Storyteller!

Eventually, the Storyteller gets conned himself--turned into a hare! And then, a flea!

The beggar proceeds to entertain the king, only to abduct his son with a magic trick.

After everything unravels, the Storyteller offers his explanation--his greatest story.

A Story Short

Contact: lostnostalgiaproductions@gmail.com

Website: www.lostnostalgia.com

Like what we're doing? Please consider throwing us a dollar into our Patreon page's tip jar!