Mario Bros.

Mario Bros. Arcade

Platform: Arcade

Mario Bros. marks the first appearance of the eponymous star's famous brother, Luigi.

Mario, Nintendo’s blue-and-red, mushroom-loving mascot, is a shape-shifter. He changes with his games, bouncing between roles and responsibilities as much as he does his powerups. He’s Champion of the Mushroom people. He’s a race car driver. A dance maniac. A doctor. A living slip of paper tucked within a pop-up book…an ever-morphing paradox that, despite universal recognition, defies a strict definition. He’s a hero, some might say, of a thousand faces.

This versatility, of course, comes from his profitability. The more games that feature his likeness, from soccer to Picross, the better the sales. Even in his earliest days, the character was everywhere: A carpenter in Donkey Kong. A demolition man in Wrecking Crew. A construction worker in Pinball. But all these appearances brewed a mystery. Who really was this “Mario?” This renaissance man? This jack-of-all-trades of such fluid ambiguity?

The initial answer seemed to spring from 1983’s Mario Bros., a hectic platformer that sent the rising star diving into the sewers. Now a plumber, and now paired with a brother, Mario’s job is to clear the slimy depths of the odd pests constantly popping from the pipes above. What were these weird creatures, these inexplicable “shellcreepers” and “fighter flies” and “sidesteppers” that kept springing from the spigots? Where were they coming from? What did they want? The questions coalesced into the first accepted Mario Mythology, one that later stated, or at least supposed, that Mario and Luigi had found their way to the Mushroom Kingdom through those very pipes, beginning the “Super Series” still continued today across the globe.

It did more than just establish the classic canon, however; it crystallized the “jump” into being the series’ genre-conquering mechanic, a now-franchise staple. Leaping was no longer just a defense or means to an end, but the key to defeating enemies—by punching the platform directly below the skittering critter, Mario could flip it upside down, then jump up and punt it from the screen. It was a seemingly trivial, even insignificant development. But it proved fundamental to Mario’s later adventures and became intrinsic to his character, defining not only who he was, but the entire series to follow. It was his super power, and the lifeblood of what made a “platformer” fun. Players merely hopped in games like Donkey Kong. In Mario Bros., players bounded to heights that outright defied physical law.

It’s ironic, then, that for all its influence on the genre’s later evolution, the game made little mark on its own category—what would be later deemed the single-screen platformer (SSP). As Nintendo pushed the character forward, plumbing the opportunities afforded by scrolling planes and, eventually, 3-D landscapes, the SSP would fall like a tossed hand-me-down to the smaller studios still willing to experiment with the classic experience. Hence, Taito’s Bubble Bobble, Toaplan’s Snow Bros., and Jaleco’s Rod-land, excellent games that proved that the single-screen wasn’t so much a limitation as a different way of thinking.

Which puts Mario Bros. in a dubious, losing position. Despite providing a kind of intense, dynamic exercise in survival few SSPs can match, it seems forever cursed for being what it’s not—the non-scrolling, non-super precursor to a greater, more lively adventure. Mario Bros. is about winning points. Super Mario Bros. is about winning a princess.

One was doomed to lose.--D

Publisher: Nintendo

Developer: Nintendo

Release: 1983

Genre: Single-screen Platformer

The turtles, called Shellcreepers here, are obvious prototypes of the later Koopa Troopa. They can even leave their shells--seven years before Super Mario World.

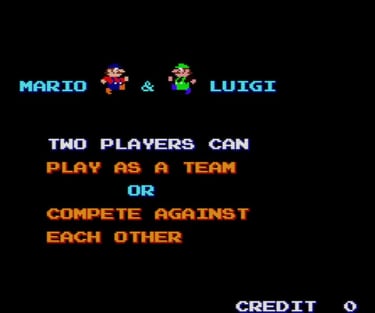

The SSP's tradition of offering co-op play arguably began with Mario Bros.

Later stages, or "phases," get extremely hectic. That POW Block, which can be punched to topple every enemy on the screen, becomes increasingly precious.

Wonder where the "freezie" item comes from in the Super Smash Bros. series? Well, he's a Mario Bros. foe known as "Slipice," a name that says it all.

Contact: lostnostalgiaproductions@gmail.com

Website: www.lostnostalgia.com

Like what we're doing? Please consider throwing us a dollar into our Patreon page's tip jar!