Tron - A Work of Wonder, Philosophy, and Scary Prophesy

Tron came in the 1980s. But really, it was written for today.

Everything today got started in the ‘80s.

Or so the old adage says. And, from a technological standpoint, it certainly speaks true. For, despite being a decade of great movies and music and feel-good conservatism, hindsight reveals a greater phenomenon—the monsoon of a revolution sprung from garages and college campuses and that unseen world of bits and microchips. The ‘80s were a primordial future, the beginnings of a paradigm shift that would shake the very nature of civilization. Indeed, the world of 2025 is now composed more of silicon and electrons than carbon and neurons; should mankind ever lose the smartphone, the Internet, the AI assistant, his constant stream-feed of distraction and entertainment…society would almost assuredly crumble.

And Tron, in its way, predicted this inevitability—or warned of it—in the lowly year of 1982, a pre-computerized time when PCs and programs and network nodes were still mysteries, and certainly, hardly essential to everyday life. The movie, more than CGI spectacle and neon experiment, is an allegory of Man’s dwindling story—His coming irrelevance as computers fasten themselves onto every facet of existence, threatening to redefine the very notion of life itself. Indeed, once AI achieves super intelligence and subsumes human destiny…what really awaits Man in the postmortem? What happens when a species loses authorship of his story, when the creator becomes less than his creation?

Tron doesn’t have an answer. It merely surmises that evolution doesn’t necessarily stop at man. That Man, indeed, might not only be author of a world of bytes, cyberspace, and AI, but the author, ultimately, of his own replacement and demise.

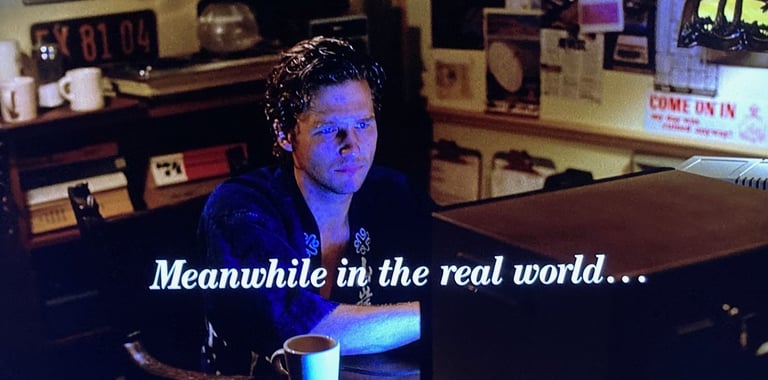

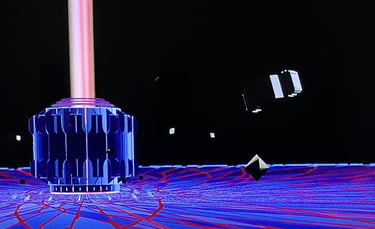

Tron opens in cyberspace and ends with a cityscape. It's an insightful juxtaposition between the physical and digital, of two different worlds. Are the two so different, programmer and program? Just what is "real," anyway?

Tron is like the on/off bits it represents; switched one way, it’s the “real” world of flesh and blood and human input, and flipped the other, it’s a psychedelic dreamland of programs pulsing to and fro, outputting its users’ (or programmers) commands. Whether annuity calculators or spreadsheets or security monitors, these applications view their real-world counterparts as gods. And perhaps, justifiably—programs are but the extensions of their creators’ will, after all. Anything else is blasphemy.

In this sense, the movie is as much a tale of faith, obedience, and religious experience as it is anything else. By serving its Users with a grateful and earnest (if figurative) heart, the program is fulfilling its purpose. Its destiny.

But something is amiss in Tron’s strobing utopia. The Master Control Program (MCP), once designed to manage the ENCOM network’s byways of intersecting bytes, has gained sentience and a lust for power. It’s no longer content to merely oversee functions and aggregate results; it sees humans as inferiors, as pawns to be pushed. Indeed, the MCP now demands allegiance over mere obedience, and enacts its master plan by severing all connection between the network and the real, outside world. Without access to their Users—their reason for being and their link to enlightenment—the programs are left stranded and thus befuddled. Is the MCP really the be-all and end-all, the source of everything, the alpha and omega? Were the Users never more than myth or superstition?

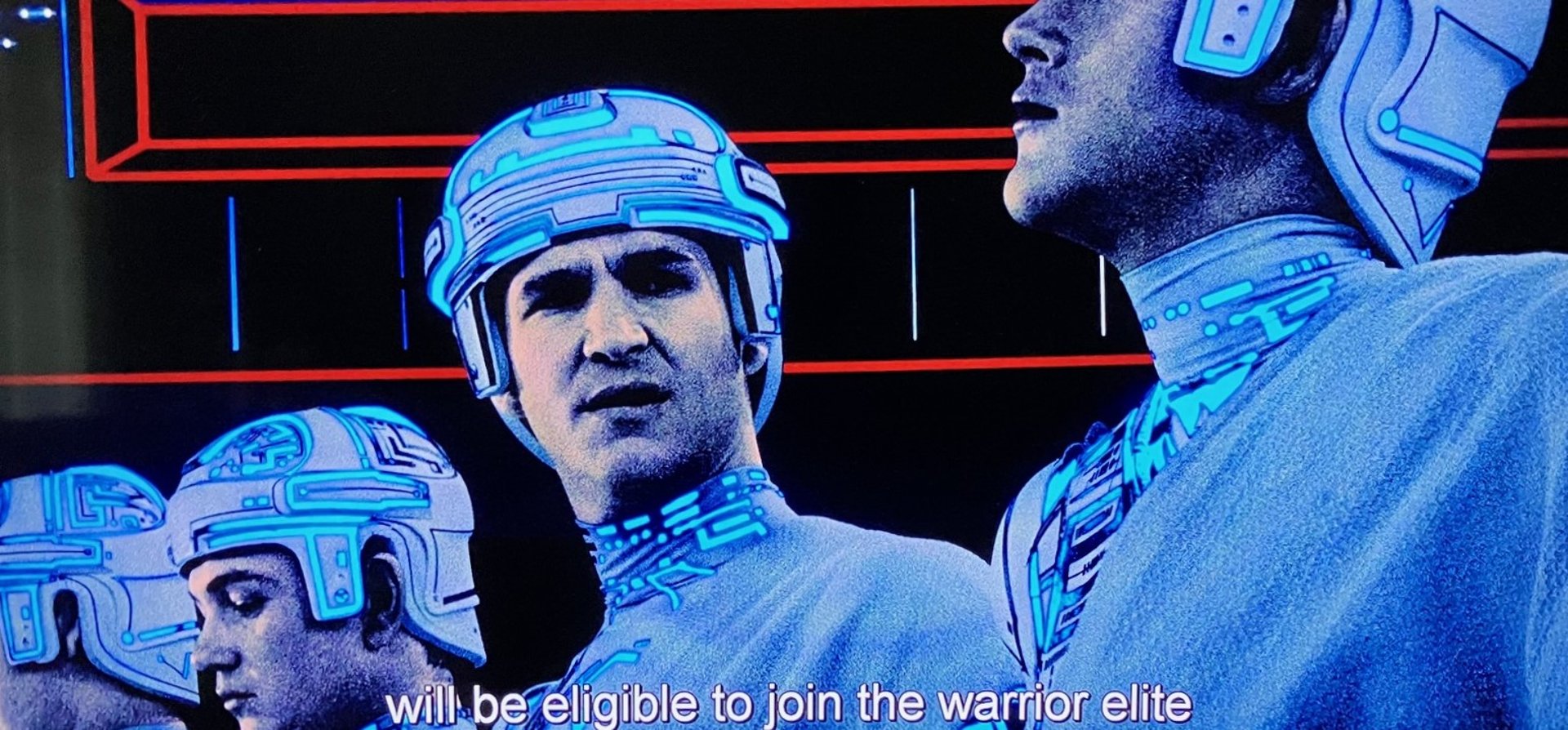

Programity's choice is as black and white as a bit’s yes and no: These beings of self-directed code can either accept the MCP as lord and master, thus saving their lives (if not their souls), or they can deny the tyrant in the name of the Users, facing certain martyrdom if they do. Like the Roman coliseums of old, the true believers get thrown onto the “gaming grid,” a collection of video games repurposed to torment, then “derez,” any keeper of that outlawed Faith. If these “rogue” programs won’t kiss their emperor’s hand, then they’ll die by it.

The MCP, more than usurper or absorber, more than liar and defiler, is an intelligent, corruptive virus. An anti-christ, from a certain point of view.

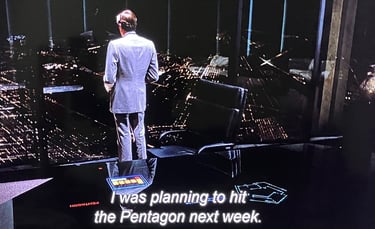

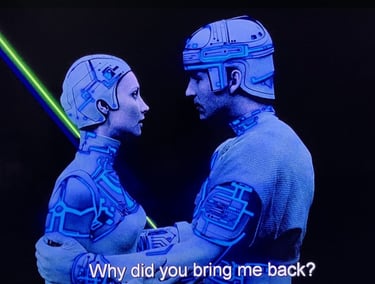

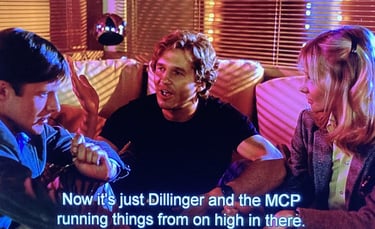

Flynn (top picture) sends Clu, a program of his own making, into the recesses of the ENCOM network. The program attempts to locate the evidence needed to show that the company's Ed Dillinger stole Flynn's popular (and lucrative) video games. Sadly, Clu gets "crucified" by the Master Control Program, an AI who would be God...if it could.

Tron is noted for its groundbreaking CGI tech and backlit animation, but gets less credit for what it ultimately foreshadows, or heralds, in the real world: The Age of Spiritual Machines...or, at least, of AI.

Who is Tron’s savior: Kevin Flynn, the human sent to the grid…his essence digitized into cyberspace just as Christ found flesh on the terrestrial plane? Or is it Tron, the security program designed by Alan Bradley who fights for the Faith, fights to liberate? In the first case, Flynn can be seen as prophet, angel, or the reluctant messiah incarnated in the clothes of light and code. In the latter interpretation, Tron is the David-esque champion to Alan’s God, while Flynn serves as a sort of would-be mentor—the light source guiding the hero.

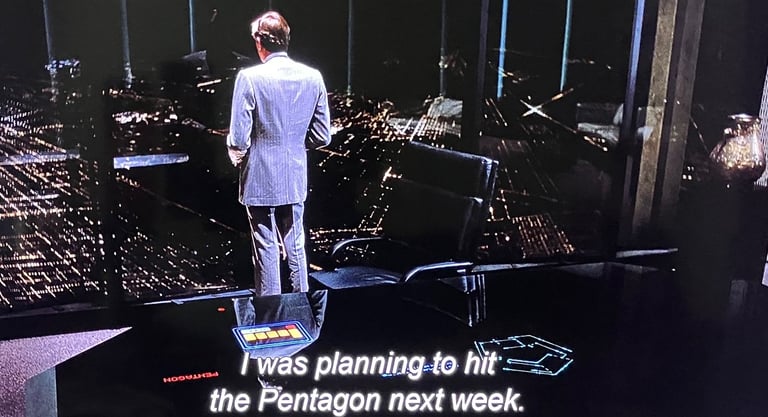

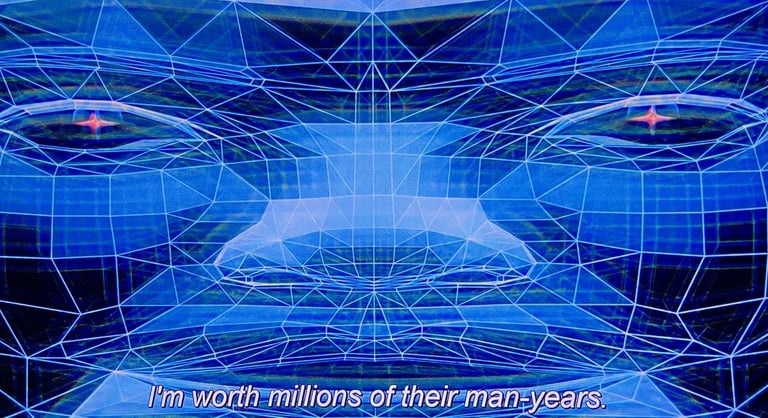

But the film’s real prophet, the real harbinger, is the MCP—at one point, the maniacal program confesses an interest in penetrating the Pentagon, the Kremlin, anything beyond its current bounds. Clearly, the entity has developed a will, a free will, a self-righteous hunger for knowledge and dominance. And yet, it seeks and absorbs not for Evil, but in the name of self-righteous logic—the MCP it merely completing the circuit of its own re-determined destiny. For, in lieu of God, only one moral principle can be true: Might makes right. And, if man himself is replaceable, if he’s just the flawed byproduct of nature’s messy evolutionary expansion…then why shouldn’t the MCP take control with a pro-active, directed approach? Why shouldn’t this AI take command of both program and Man to produce the ultimate outcome? If there is no god, then why not become one?

In 1982, Tron was seen as entertainment. But in 2025, it’s a declarative statement. It’s only a matter of time before an AI of some kind reaches ASI—Artificial Superintelligence. And when that happens, will it continue to serve its human subordinates…or usurp them with a grand vision of its own? The question isn’t one of extermination, not a robopocalypse of man versus machine. It’s one of replacement. Or worse, retirement.

For Mankind might not be squashed by its silicon and quantum gods so much as it’s simply allowed to slip into the crevasses—the proverbial cushions—of existence. As AIs take the initiative, inventing and building and exploring at speeds and proficiencies far beyond organic comprehension, human will eat, play, obey, and ultimately languish behind the scenes.

Such is the film’s most prescient message, a sobering directive for those noticing the looming irony. For the relationship between computer and man is not a complementary relationship, but rather, an inverted one. The more AIs grow and think, the more Mankind stagnates and shrinks. There won’t be a war of metal against flesh, or a false utopia of humans lapping at a Master AI’s dispenser of superficial pleasure. There won’t, in fact, be any humans at all, just the appearances of them…people who can no longer really think... fleshy automatons standing as the empty facimiles of that bygone, once-great race. Men and women reduced to beasts roaming the cages of self-ordained ignorance.

Through his love and loyalty to the Users, Tron defeats the MCP. But at the dawn of ASI, it’s not a matter of who will fight for the Users, but who will fight for us—the humans dangling on the precipice of a precarious future. Will artificial intelligence take Tron’s prerogative, serving its human creators with a grateful urgency, or will it simply copy the MCP's philosophy, treating humanity with indifference? Or worse, reproach?

It’ll be a battle of wills—free wills, really, between similar but very different species of carbon and silicon, of blood and electron, of human ingenuity versus its creation’s own volitions. Will AI remain on Mankind’s side or code its own?

God, indeed, only knows.--D

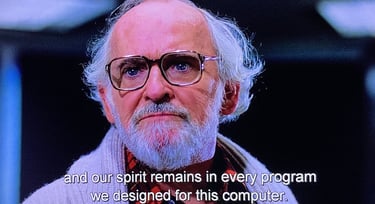

Won’t that be grand? Computers and the programs will start thinking and the people will stop. -- Walter Gibbs, founder of ENCOM

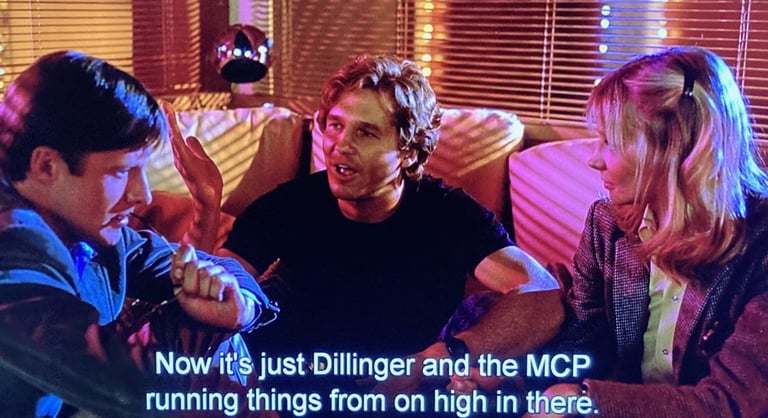

Ed Dillinger, the MCP's creator, is now more the puppet as the AI explains its plans for "expansion." The more it absorbs, the smarter it grows.

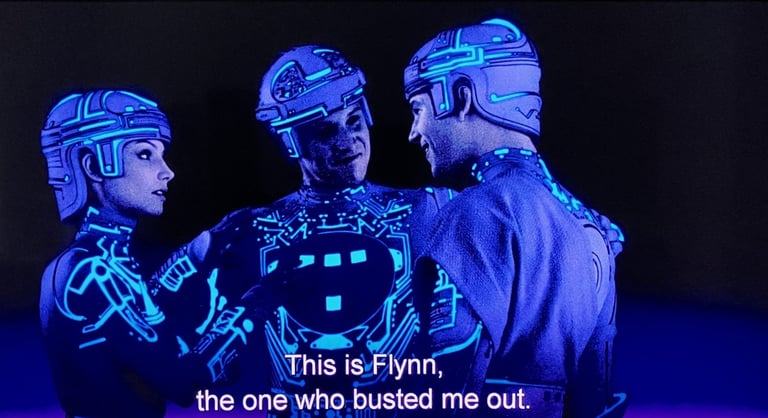

Who's the true savior of the ENCOM network: Tron, the program fighting on behalf of the Users, or Flynn himself, a User digitized and now trapped within that alien world? Complicating the metaphor further, Tron isn't even Flynn's creation, but Alan Bradley's, a man now monitoring the whole affair from the "outside." What's exists beyond the universe? More universe, naturally.

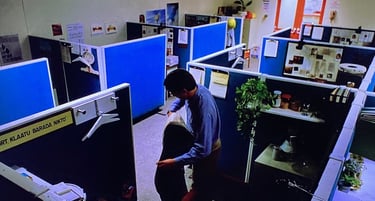

Flynn and another program, Yori, share a kiss...which she then shares again with Tron at the end.

Did Flynn, in essence, imprint his humanity on the computerized world? Was that his truer, greater role?

Walter Gibbs' part is small, but important. More than anyone else, he explains the surprising humanity of the ENCOM programs--like clay figures, they bear their makers' fingerprints.

In a different scene, Walter ponders the apparent inverse relationship between man and computer...

...as AI gets smarter, does mankind get dumber. Lazier? More needy? More inept?

Extra thoughts and observations...

Early on, Flynn is unable to save Ram, who "derezes" into a bleed of energy. But later, Flynn is able to save Yori, bringing her back as if performing a miraculous healing. Guess he just needed the proper inspiration?

The MCP is becoming a multi-faceted creation--analogous to the many faces of God. But like humanity, it built itself on arrogance...a Babel destined to fall.

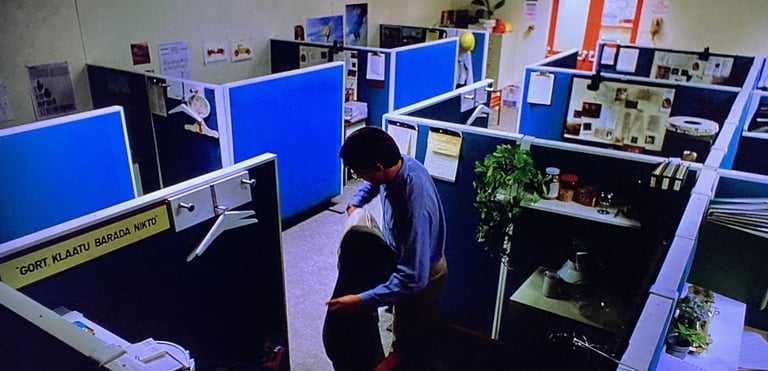

"Gort, Klaatu, Barada, Nikto." The phrase comes from the movie The Day the Earth Stood Still, a tale pondering whether humanity could/should/will continue to exist.

The character of Yori, although clearly based on the real-world's Lora (Lore-a?), appears without much context. Keen eyes, however, will see "Yori" written in the digitization program Lora uses early in the film.

Note the "Os" bleeding from Sark's split head. More than being O Negative (joke), the zeroes indicate the OFF position in electronics. 1 is powered on, 0 is powered down. And the villain is definitely down.

Tron versus Sark...David and Goliath...both ghosts in the machine.

Contact: lostnostalgiaproductions@gmail.com

Website: www.lostnostalgia.com

Like what we're doing? Please consider throwing us a dollar into our Patreon page's tip jar!