Hayao Miyazaki is world-renowned for good reason; his illustrious Studio Ghibli is famous for its exquisitely animated films, many of which explore the tensions between man and the natural world. Sometimes whimsical, sometimes fierce and forceful, his tales have depicted humanity as stewards of peace or purveyors of war, Mother Earth as a generous or hostile force. Can both entities live in harmony? Or is one destined to destroy the other?

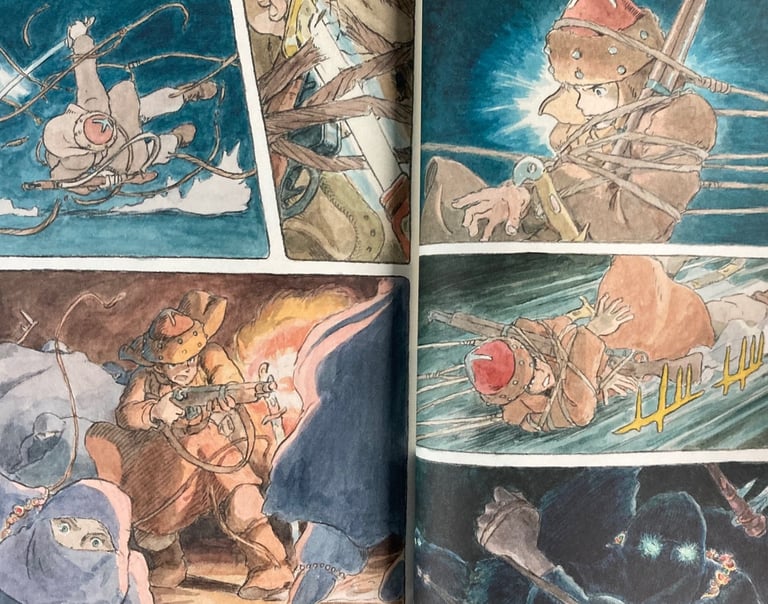

Miyazaki is also a quick study of the human condition, depicting his leads, usually female, as courageous agents bearing and braving life’s capricious demands. Some of these stories are simple, slice-of-life affairs focusing on family or community. Other tales are sweeping, heavy-handed epics, featuring wars and angry gods and dead civilizations, with mankind often the cause or at least entangled in-between.

Shuna’s Journey, interestingly, is none of these things. Not exactly.

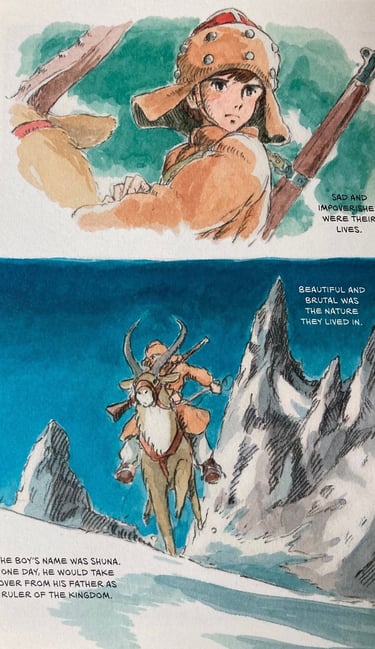

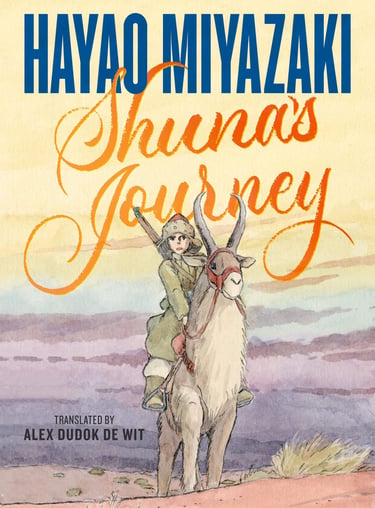

First, it’s not an animated film or TV series. It’s not even a manga in the vein of Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind, another classic Miyazaki work. Rather, it’s an emonogatari – an illustrated story that deemphasizes word and manga-style paneling for captions and (often) full-page art. A close American equivalent would be a hand-drawn children’s book or, more explicitly, Neil Gaiman’s Stardust, a graphic novel in which the author combines skeins of text with singular illustrations to convey an engrossing story. Shuna’s Journey pushes the format to its fullest potential.

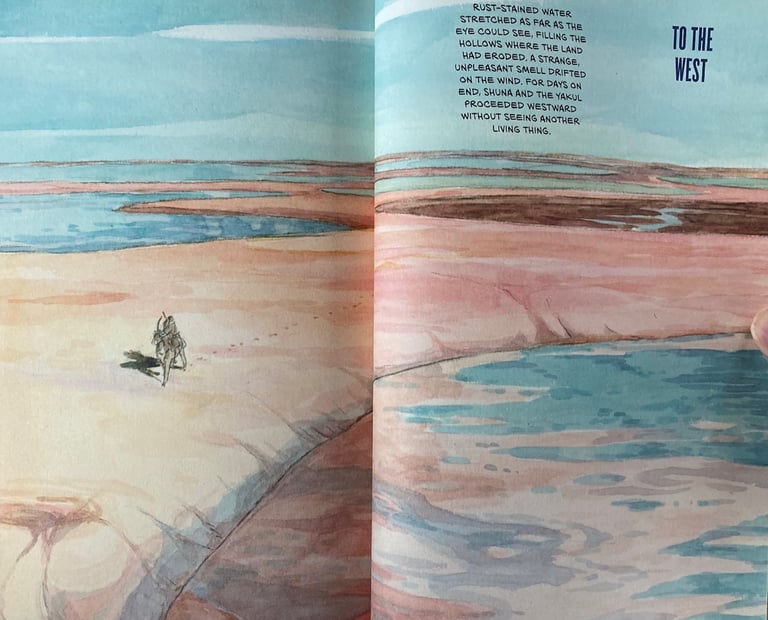

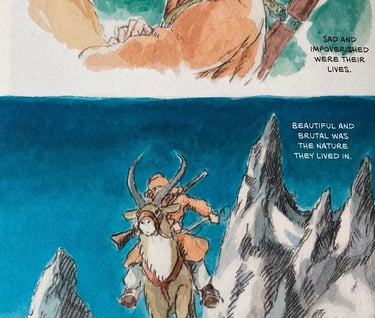

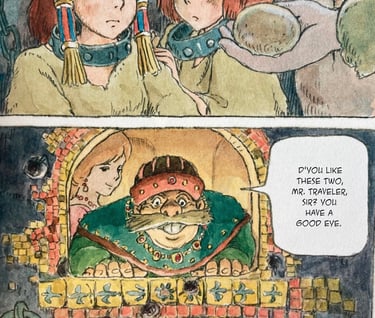

Second, the story is neither epic nor simplistic, but pivots somewhere between the extremes. The eponymous Shuna, the story’s princely avatar, doesn’t leave his quaint homeland to save the world or defeat some terrible evil. Rather, he seeks a special seed—an almost magical grain that promises to forever feed his suffering tribe. And though the young man certainly encounters some danger and excitement on his journey, he spends much of his time simply wandering across landscapes both beautiful and barren, familiar and alien. Here, Miyazaki’s lushly painted pages become the star, filling in the silence of Shuna’s lonely travels with exotic sights and twisted lands that hover between dream and hanging fear.

Lastly, the story doesn’t hold to a specific genre. It’s an adventure, maybe, but not a fun, swashbuckling one. It’s almost a piece of heroic introspection, except Shuna is so stoic to his core, little growth or personality is revealed. It’s about the Earth, yes, but humanity is more the victim here, exploited by both his fellow man and a strangely cryptic, unyielding planet. It’s a tale of love…that goes unstated. It’s a mystery without resolution or proper payoff. Ultimately, it’s a paradox that tantalizes as much as it teaches, dangling scant hints and intimations to explain an incomprehensible, even horrific set of circumstances. In fact, the tale is borderline nihilistic—a strange row to hoe for the usually optimistic author. But hope peeks through the book’s final pages, offering its characters, and its readers, a reason to still believe.

The story, to its detriment, is also a curiosity, unintentionally serving as a prototypal preview of later Ghibli films, most notably Princess Mononoke. These parallels to later works prove as distracting as they are fascinating, diminishing the potency of the original story. If possible, Shuna deserves to be read first, safe in a vacuum far away from the author’s other masterworks. Again, if possible.

Beautiful, ponderous, inexplicable…Shuna’s Journey is Miyazaki’s imagination left to the wind, flowing and unfurling like leaves traveling without destination. Indeed, the story doesn’t conclude so much as it pauses, suggesting a part two that never came. Thus, the story feels more like a fragment dredged from some lost, religious text…incomplete but not insignificant. Some might want more, but readers less concerned with explanations and more willing to be moved and stirred by the images and words contained therein, will find a work primal, timeless...

...and unmistakably Miyazaki.--D