Antz

(Junior Novelization)

Author: Ellen Weiss

For fans of the underrated film (which, at the time, had been overshadowed by Pixar's more cutesy A Bug's Life), this little novelization does an adequate job of capturing its counterpart's dark, quirky charm and surprisingly intelligent commentary on hive mind conformity versus independent thought. If that sounds too deep (too unfun), don't worry--the book keeps the quick-footed pacing of the film, totaling a mere 117-pages. Indeed, it reiterates each movie scene almost too efficiently, leaving those like myself a little disappointed there wasn't a bit more to discover beyond what the movie already contained.

Of course, this was intended for kids. And from that standpoint, it surely succeeds in its brevity despite retaining some of the more "gruesome" moments and ideas that could alarm a protective parent. Yes, characters die in rather gruesome, bug-specific ways, from incineration (under a magnifying glass) to being crushed beneath a merciless fly swatter, all while the leading villain actively seeks to enact genocide against his own kind. The book doesn't dwell on these matters too much...but they're there.

Nevertheless, for those who would be reading this scant, forgotten pamphlet ages after its original release, this makes for a fun snack between greater, more substantial reads, junior variety or otherwise. Its foremost metaphor--that one’s independence can bring eventual deliverance, remains a timeless creed well saved within its pages. And it made me want to watch the movie again.--D

Socks

Author: Beverly Cleary

As shown above, Socks has received a number of reprints and reissues over the years, often with unique art and branding. Note the competing taglines between the latter two examples.

Although the modern marketplace of junior fiction favors books of a more extraordinary bent, there once was a time in which children enjoyed tales of the mundane as much as those of derring-do, fantastical beasts, and wizarding schools. Not everything needed to be crouched inside a magical motif or mystical backdrop; books could be about going to a new school, dealing with an obnoxious kid brother, finding a stray dog, living on a farm, and any other number of everyday, relatable matters.

And the queen of this slice-of-life style is the late Beverly Cleary. While working as a children’s librarian in the 1940s, she noticed how few books truly catered to the grade-school age and mindset. Kids would enter her land of tales only to leave curiously unhappy or empty-handed. And so, she resolved to fill that void herself.

Hence Socks. It’s not the first book she wrote—her illustrious canon is filled with plenty of works that came before, from The Mouse and the Motorcycle to Ramona the Pest—but it’s perhaps one of her best. Certainly, one of the most underappreciated.

It’s a seemingly simple tale that sees the eponymous cat, named “Socks” due to his white paws, living a charmed life with the Brickers, a newly-married couple who dote on him at every turn. At least, until the baby arrives. Socks is no longer the center of attention as newborn Charles William takes command of the couple’s lives. Worse, as the cat tries to cope with his family's sudden indifference, his mostly innocent behavior only gets him into trouble. Soon, the indoor pet finds himself exiled outside with only access to the garage. And the tragedy, really, is that he can’t understand the why behind any of it--why is his loving family now being so cruel?

No doubt, while a superficially cute and humorous tale, true melancholy is laced throughout—Cleary, a cat owner herself, clearly understood the feline mindset, and did wonders turning Socks into a believable, sympathetic protagonist despite him being, well, a “stupid” animal. And ultimately, that’s probably the point. Is Socks really so primitive? Might he have his own valid perspective and feelings? It’s easy to say ‘no’, of course—that he’s just an animal. But Cleary knows otherwise.

Here’s a quick excerpt after Socks is banished outdoors:

Still, his [Sock’s] heart remained in the house with his family. Loneliness and curiosity drove Socks to spend more and more time sitting on the windowsill watching all that went on inside…He watched Charles William grab Brown Bear by one leg and beat him against the playpen pad, and he heard him shout, “Id-did-did!” He was curious for a closer look at the plastic ball filled with water and sloshing plastic fish. He saw Charles William support himself on his hands and knees and crawl across the pen…

Imagine being divorced from one’s family and left to only observe, while ignored, through a pane of glass. Every moment, every new development, now reduced to a one-way mirror. This is Sock’s life now, as Clearly so ably shows.

She’s also a shrewd observer of feline behavior, as seen in the cat’s indignation at suddenly being locked in the laundry room each night (after being allowed to roam free):

Socks resented the arrangement. Every evening he complained himself hoarse…Socks lay yowling on the hard floor and groped under the door with his paw. He sat up and threw his shoulder against the door. When nothing, absolutely nothing would free him, his last act before settling down on the sweat shirt [his bed] was to plow Kitty Litter over the floor so someone would have to sweep it up in the morning.

Indeed, cat-friends will find the author's descriptions humorously faithful to their own experiences.

It’s this rapt regard for the feline persuasion that helps Socks transcend its grade-school trappings. Anyone puzzled or amused by his own cat’s quirky or seemingly self-entitled behavior will enjoy Cleary’s keen take on the feline mind and likely gain a bit of empathy. But it’s the cat-hater—those that sniff derisively at the very notion of a cat—who would, ironically, benefit most from the book’s hidden wisdom.

It’s hard for anyone, even the haters, to despise an underdog. Cats around the world can only hope more people read Cleary’s unassuming masterpiece; Socks might just be the perfect ambassador for establishing peace between cat and man.--D

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz

Author: L. Frank Baum

A young girl named Dorothy gets whisked to the magical realm of Oz, a land where anything can happen. Joining forces with a living scarecrow, mechanical tin man, and talking lion, they seek to defeat an evil witch and meet with the eponymous Wizard—the one who can fulfill their deepest needs.

Everyone knows the 1939 film, The Wizard of Oz. It’s one of the few movies to escape its era and become a sort of timeless vehicle still known by generations today. The characters, the music, the switch from grim black-and-white to glorious color, all combine to beget a tantalizing experience. Wouldn’t it be dreamy, indeed, if the Land of Oz were a real, reachable place?

People forget, however, that the movie came from a book—the first, in fact, of a fourteen-novel series all conceived by the (apparently) very eccentric L. Frank Baum. His later works are all but forgotten now, but once upon a time, these were popular fodder for children. Today, the modern kid would probably run away screaming if given a copy, and not because these stories are awful. They're just weird. Inexplicable. A little disturbing. And, at times, outright scary.

The first book is perhaps the tamest of the series, but even so, the 1939 movie wisely omits some of its grimmer, more unnerving scenes and developments. Take this bleak description of Dorothy’s home in Kansas:

“The sun had baked the plowed land into a gray mass, with little cracks running through it. Even the grass was not green, for the sun had burned the tops of the long blades until they were the same gray color to be seen everywhere…When Aunt Em came there to live she was a young, pretty wife. The sun and wind had changed her, too. They had taken the sparkle from her eyes and left them a sober gray; they had taken the red from her cheeks and lips, and they were gray also. She was thin and gaunt and never smiled now.”

The movie uses this dour description as a clever juxtaposition device, depicting the real world in monochrome drab while rendering Oz in resplendent technicolor. But for readers unfamiliar with the film, this joyous contrast between the two is not especially felt. Kansas, simply, is a veritable nightmare.

But Oz, in a different way, is the scarier place. It’s ruled by a sort of magical nihilism; anything can happen, good or bad. The Tin Woodman, for instance, was once a man of flesh and bone. But the Wicked Witch of the East cursed his axe so that, every time he swung, it would sever a limb from his body. But rather than discard the treacherous tool, he simply replaced the lost appendages with artificial equivalents made from tin. And eventually, he even swapped out his head, becoming a 100% pure, Tin Man. The movie wisely removes these icky notions.

But the book’s main problem is not the horrific nonsense. Rather, it suffers in structure, with the Wicked Witch of the West defeated in an anticlimactic confrontation long before the tale is done. It’s almost as if Baum realized the book was concluding too soon and so scurried to add another hasty adventure. The film, again, knows better: it’s all about the evil witch and, once she’s defeated, it’s time to send Dorothy back.

Is The Wonderful Wizard of Oz a worthy read? Yes, probably, thanks in part to its brevity. But the bigger question for the would-be fan is whether the entire series is worth the significant timesink. The curious should start with the first entry and, if still interested, creep into the later volumes. Kudos to those who proceed through all fourteen!

But for most, this book is best treated, and left, as a solitary volume—a fascinating peek into early twentieth century children’s literature. A quick escape into a world where, like Dorothy, a quick exit is also desirable.

There’s a reason she’s so desperate to go home.--D

Thanks to clickamericana.com for the image...

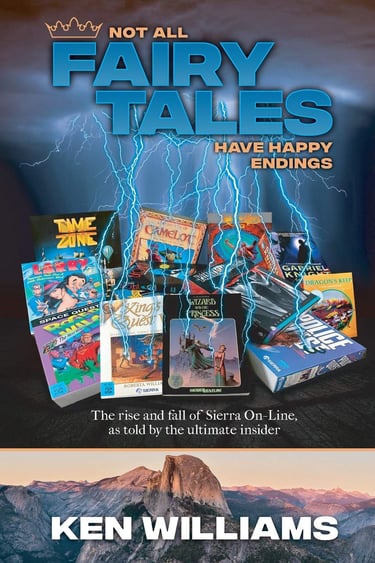

Not All Fairy Tales Have Happy Endings

Author: Ken Williams

The dawn of electronic gaming is a fascinating fracture, a big bang of separate pursuits and disparate interests that have since forged an eclectic industry. Those who grew up during the arcade’s golden age will no doubt find the triumphs and travails of Nolan Bushnell and his fledgling Atari a gripping piece of video game history, while conversely, early PC owners will find the parallel tales of an upstart Apple Computers equally engrossing. The pastime would continue to diverge and evolve throughout the ‘80s, with the arcade, game console, and home computer markets all bearing their own philosophical approaches and spreading in distinct directions. The latter was perhaps the most homespun and “eccentric” of the bunch, possessed by an off-the-cuff sensibility that the upstart Sierra On-line embodied perfectly as it came into being.

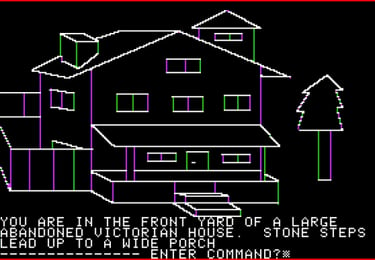

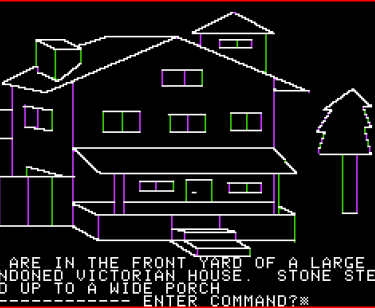

Long before its 2004 closure, Sierra On-line was a software superstar, as famed and legendary in its day as Valve and Activision Blizzard are now. Helmed by a young and fearless Ken Williams and his indomitable wife Roberta, the two authored the first graphical adventure game—1980’s Mystery House—which garnered instant success and helped ignite the Sierra empire. For the next sixteen years, the company (coined "On-Line Systems" initially) would grow in both prominence and prestige, authoring dozens of popular titles. It was always on the cutting edge, always experimenting, always diversifying. Sierra was beloved and seemed invincible.

So what happened? It's complicated.

Pundits, historians, wistful fans, and former employees have long shared their own insights and theories. Who was really to blame for the famed studio’s downfall? Naturally, Mr. Williams receives much of the criticism—accusations he’s never tried to aggressively refute or explain. But those seeking the truth, or at least some closure, might find it here; some twenty years after the company’s downfall, Williams finally shares his side of the story. And though it smacks of being too little, too late, it’s still an engaging read for who have always wondered why Sierra just seemed to suddenly disappear.

Williams begins his tome speaking of his youth, his college days, his courting of Roberta, his introduction to the computer revolution, and finally, Sierra On-Line’s rise, heyday, and demise. The book strikes a wobbly balance between in-depth insight and more cursory recounting; no doubt, some will wish Williams spent more time discussing the formation of certain games, the company’s party-centric sensibilities in its earliest days, the individual designers and personalities who gave Sierra its distinctive flavor, the author’s opinions on competitors such as LucasArts and Infocom, and how he coped emotionally with both the stress and embarrassment of Sierra’s downfall. What readers get instead is a collection of the author's thoughts on a hopscotch range of topics. Acquisitions. Anecdotes. Successes and failures. Management philosophies and scattered advice. Few will find the book uninteresting or completely without merit. But similarly, few will find every subject of worthy importance.

To Williams’ credit, he could have used the pages to disparage his former competitors and current naysayers, to complain about his unjust fate and loss of relevancy. But rather, he’s generally diplomatic, sticking to the facts (or at least his version of them) and letting the actions of certain personalities speak for themselves with only modest comment. If anything, he’s probably too diplomatic, too milquetoast—with himself more than anyone else. Former Sierra employees hoping for an outright apology for, say, Williams’ (initially secretive) selling of Sierra to CUC Software (which ultimately led to the company’s end) won’t quite find that here. Even so, the latter chapters do carry a taint of regret, even shame, that can’t be denied. This is not a man seeking forgiveness, exactly. Just understanding. His greatest sin, probably, was his two decades of silence.

Indeed, the entire chronicle reads like a paradox; for every victory Williams celebrates, there’s almost always an equal and opposite failure waiting a few pages later. It’s uncanny, really, how such a successful company could make so many constant mistakes, from not acquiring ID Software to The Sierra Network’s demise to the botched production of Outpost, a game released essentially unfinished. But that was Sierra—a brand so strong, it could withstand the incessant hiccups and iffy decisions. For that, Mr. Williams is to be commended. He built a name—a reputation—truly impervious to any iceberg. Well, except himself.

In retrospect, vintage Sierra can best be likened to Nintendo. The latter, a Japanese company of monolithic proportions, carries a special connection with its fans—owns a Mario-shaped stamp on each of their hearts. That was Sierra once upon a time, a company that was more culture than corporation, an artistic movement and creativity engine that helped raise an ‘80s generation. But once the outsiders, the opportunists, the money-mongers and charlatans were given access to the throne, Sierra lost control of the narrative. Lost the folks. Lost its soul.

Fans can choose to either celebrate or lament Sierra's glory days. Blame or praise Mr. Williams; dismiss or forgive him. Just remember, it’s always the King who suffers most. Ken Williams is still rich. Successful. Has friends, a life, a devoted wife. Still holds his head high with pride.

But he’s lost the crown of true immortality.

And that’s a curse worse than death.--D

Mystery House was Ken and Roberta's first game. It doesn't seem like much now, but in 1980, this was revolutionary.

King's Quest became one of Sierra On-line's greatest franchises. Released in 1984, it was a significant advancement over Mystery House released just four years earlier.

1995's Phantasmagoria was a watershed moment for Sierra--the Adventure Genre was the company's preeminent specialty. Juxtaposed with Mystery House and King's Quest, the game made an opulent capstone for what was an exquisite 15-year evolutionary journey.

Thanks to GOG.com and retrogamer.net for the pics!

A King Ponders What He Wrought: An Elegy of Missed Opportunity

Pac-Man: The First Animated TV Show Based Upon a Video Game

Author: Mark Arnold

Pac-Man: The First Animated TV Show Based Upon a Video Game…

It’s a wordy title that at least serves its purpose, warning readers of the shallow journey waiting within. The scant 125 pages that follow hearken to the eponymous hero’s early-‘80s heyday where being round, yellow, and hungry was all the rage. After his hit arcade game led to a maelstrom of merchandise ranging from bed sheets to canned pasta, the mascot managed the ultimate score—his own Hanna-Barbera cartoon. Indeed, it was the first of its kind, a show that would inspire plenty of other game-to-toon adaptations in future years. Had the book embraced this particular premise, using Pac-Man to explore early-gaming’s influences on the greater media and cross-cultural landscape, this could have been an intriguing read. Instead, author Mark Arnold settles on a dry, “just-the-facts”-style of retrospective that offers a decent surface-level sweep of that initial TV series, but little more.

At least the book begins well, with Arnold introducing himself and explaining, if somewhat vaguely, that the book is something of a lark—a friend’s funny dare that the author decided to entertain. Normally, Arnold states, his books run about 700 pages long, but this one has been kept “short and fun.” Well, it’s definitely short.

What immediately follows is a brief “history” of Hanna-Barbera’s animated output from the 1940s onward, although it’s more akin to a series of lists forced into paragraph form—a filmography cut and pasted from a spreadsheet. Fortunately, the next chapter, A Brief History of Arcade Video Games, proves more palatable, offering some cute anecdotes into the industry’s founding. Only the factual inaccuracies disappoint (one, for example, states that the game Breakout was developed in 1972 by Steve Wozniak, but his involvement was closer to the 1975/1976 timeframe). The third chapter then moves to Pac-Man himself, offering a breezy telling of the mascot’s origin. Too breezy, really, as it reads a bit like a Wikipedia entry with its own factual error or two. (The Ms. Pac-Man IP, for instance, is not wholly-owned by Bandai Namco Entertainment despite what the text suggests. It’s shared, in part, by AtGames).

The rest of the book—the remaining 100 pages or so—lists the extensive filmographies of the cartoon’s voice cast before providing a synopsis of the show’s every episode. While appreciated, these sections would have been better left to an appendix versus being foisted as the main focus—they smack of filler hiding the lack of a plan or greater purpose. Where are the interviews with the animators, development team, voice actors, and so on? The per-episode screenshots and freeze-frame analysis? The insightful commentary on how Hanna-Barbera took an abstract, non-descript disc and transformed it, this “character,” into a walking, talking, somehow sympathetic being? Where are the pinpointed correlations that link the cartoon to the Pac-Land video game, one of gaming’s first-scrolling platformers? Why not delve into the marriage dynamics shared between Pac-Man and his winsome wife, studying the complimentary (and loving) relationship the two heroes share? For such a “pivotal” cartoon show, it’s a mystery why these deeper themes were left undiscussed. Outright ignored, in fact.

Which is to say, in a different way, that the book is as hollow as a ghost monster, an airy husk marked with only the faintest spark of insight. Those not looking for such lofty ponderings might be more forgiving, appreciating the quirky book’s custom art work, vintage pictures, and, really, that the tome exists at all. Redesigned as a coffee table book showcasing classic Pac-Man memorabilia, this superficial approach could have merit. It’s just that, as is, the effort seems unfinished. More quirk than content. A missed opportunity lacking an obvious audience. A prelude, or pretense, to something more.

Mr. Arnold, you might be on the verge of something very special here. A 2nd edition would be a great way to try again.--D

To the author's credit, the interior's design sports some spiffy art, much of which seems to be commissioned uniquely for the project.

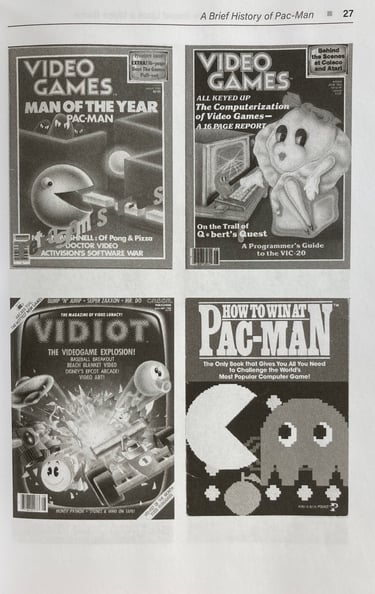

A few pages are spent displaying early Pac-Man memorabilia and merchandise. Here, the covers of various Pac-themed magazines and books are shown in full black-and-white glory.

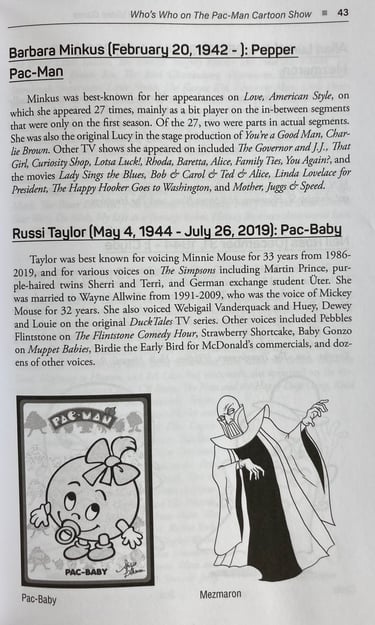

The eclectic Barbara Minkus provided Ms. "Pepper" Pac-Man with her dynamic voice. She deserves more than just a paragraph!

The front cover art is nice.