Cats Don't Dance

Don't be fooled. Not only do cats dance... they sing, joke, and make a marvelous film.

In an alternate 1939, humans are the actors…and animals are the extras, forced to take the leftover roles. And no, these aren’t creatures of the Lassie or Mr. Ed variety, but intelligent (anthropomorphic!) denizens more akin to Tony the Tiger or Baloo the Bear. Toons, essentially—“people” of a fur and feather found in any golden era animated short, from Warner Bros. to MGM.

Indeed, Cats Don’t Dance could have easily been another Who Framed Roger Rabbit, with the humans serving as the live actors, and the animals portraying the discriminated toons. The film even shares the same time period as the Rabbit’s, featuring a gilded, idealized Hollywood decked in all the classical trappings. Clark Gable. Laurel and Hardy. Joan Crawford. More than a few famous faces grace the movie’s front and backends, most of which younger audiences won’t hope to recognize.

But no, this is an animated production that both follows the traditional recipe—hero must overcome adversity to achieve his dreams—while daring to break some of those very same eggs. Up until 1997, Disney had defined the form’s style and formula, relying on feel-good fairy tales and similar fare to reap its profits and critical awards. The company was not interested in parables of social justice or metaphors of induced inclusion. The overwrought, diversity-driven version of present-day Disney was still many years away.

The folks at (the now absorbed) Turner Feature Animation, however, did what was unthinkable for the era—it crafted a movie of serious theme while wrapping it all in a cartoon's winsome, irreverent skin. Imagine Bugs Bunny, in all his stretchy, wacky stylings, fighting for racial (or species) equality in a 1940s-esque motion picture. In Cats Don’t Dance, Danny is the rubbery, naive feline who does just that. Optimistic to a fault, he dances and hopes and schemes a path to his big break. It’s the American Way; despite show-stopping adversity, he still achieves The American Dream.

Wisely, the notions of prejudice are tempered by what is still a wacky, almost paradoxically simple picture. Danny travels from his quaint hometown of Kokomo to seek his dream in the West, giving himself a week to land his first major role. And, despite the hardships he soon encounters, he essentially succeeds…defeating the oppressive studio regime to find stardom in just a flit of days. Representing that regime is the faux-adorable starlet Darla Dimple, who, along with her monstrous servant Max, does everything she can to sabotage Danny’s constant plans for success. Why the film chooses her to carry the blame for the industry’s sins (versus, say, studio head L.B. Mammoth) is a curiosity best left to conjecture. But she makes an excellent villainess, providing a sharp, even scary counterpoint to the ah-shucks Danny. She stands among the great animated antagonists.

But the real delight, if truth be told, is not the progressive message or psychotic tot. It’s the animation, which evokes the best of Popeye/Red/Tom and Jerry while barely seeming to try. No other work quite compares; the film offers more stretchy zest than Don Bluth’s best, and it handily matches the spastic quality that made Roger Rabbit so compelling. The message of social acceptance is indeed a good one, but once the characters begin prancin’ and scrappin’ and caterwaulin’ along, it’s easy to forget everything else—seeing only the movement, the color, and the elation that comes with such a high-flying defiance of physics. Those inclined to try a freeze-frame analysis will find an instant gallery of eclectic cartoon art, all courtesy of an animation team at the absolute peak of its craft.

The music is also inspired, featuring upbeat songs written by Randy Newman and sung by such greats as Natalie Cole. Moreoever, the peerless Gene Kelly even served as the film’s choreographer for many of its dance-happy musical numbers. The movie is truly a blending, and a celebration, of everything old and new.

And bitterly, it went unloved at release, garnering a meager $3-4 million at the box office before getting scuttled onto VHS cassette and promptly forgotten. It was at home, though, that the movie got its big break; the TV set finally gained Cats some visibility and respect. Today, the film is regarded as one of the finest (non-Disney) examples of theatrical animation, perhaps falling just behind The Iron Giant. Better yet, it received the Warner Archive treatment in 2023, being revitalized and optimized for its first Blu-ray release. Perhaps this upgraded edition will garner a new generation of fans for this dancing cat and his cast of Hollywood hopefuls--abetted by the now ubiquitous, wide-screen television display that turns every household into a miniature theater. The movie has never looked sweeter.

And likely, beyond its odes against prejudice and discrimination, Cats Don’t Dance will be remembered for that—a fantastic dance back to a simpler time in which cartoons could be anything…and hand-drawn art wasn’t just cool, it was the rule.--D

Meet Danny, a scrappy, slaphappy cat with gigantic, fantastic dreams. The denizens of Kokomo certainly love him; why would Hollywood be any different?

The movie has fun with its Hollywood references and in-jokes. As seen in the bottom pic, King Kong's "actor" is seen carrying off a faux Empire State Building.

The cat's supporting cast, including Sawyer, his pretty-kitty love interest, and Pudge, his penguin best buddy.

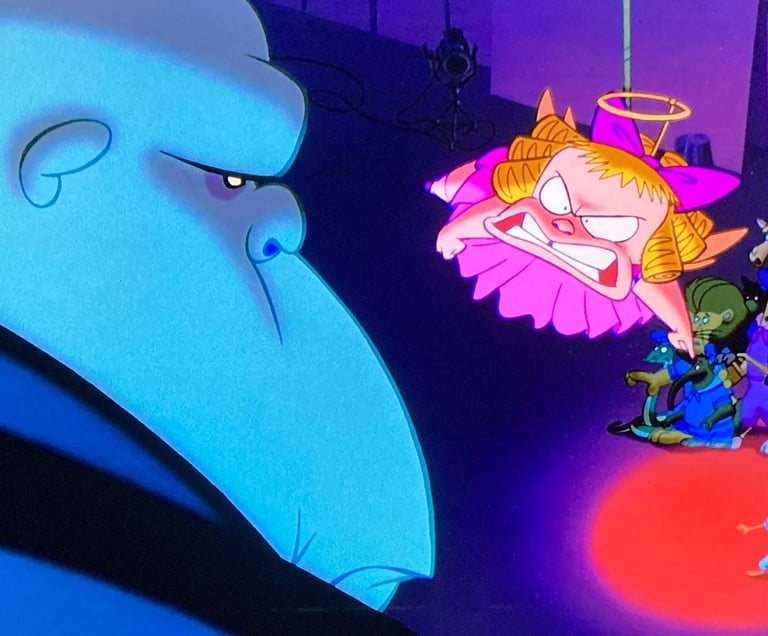

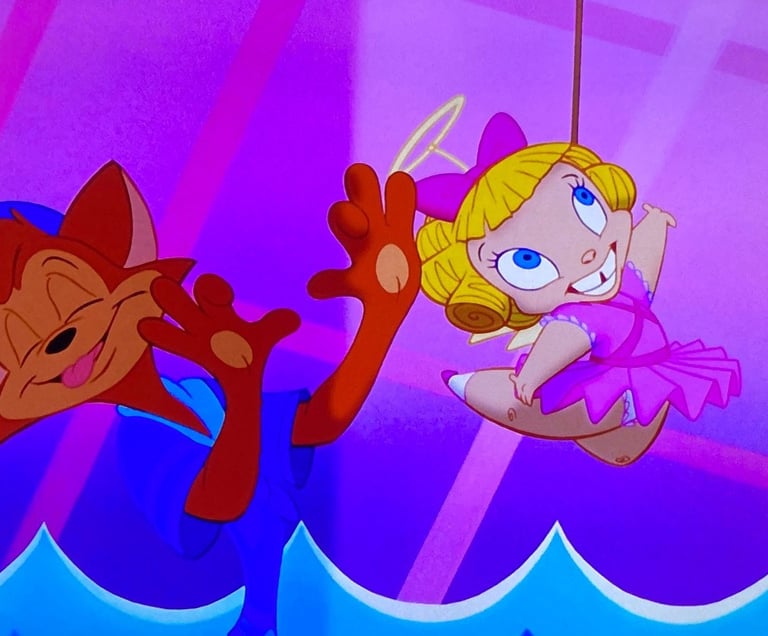

Darla Dimple and her hulking butler Max serve as the film's villains. Darla is adorably deplorable, and Max is like a skyscraping Darth Vader mixed with a gorilla and Frankenstein's monster.

The movie is split into simple thirds. The first act sees Danny's arrival in Hollywood, receiving a part on the Lil' Ark Angel production, and facing a fast humbling at the hands of Darla (or rather, Max).

Danny's next attempt to gain everyone some recognition is quickly and epically sabotaged. Darla, seizing her opportunity, floods the soundstage and humiliates the entire animal cast just before they can perform.

Danny tries once more, this time planning an impromptu, surprise performance before the audience at Darla's Lil' Ark Angel premier. This time, he succeeds...

Sawyer might be the among the loveliest non-human creations ever committed to screen. Her designers and animators should all be commended.

The film screams to be freeze-framed. Every scene is a veritable gallery of incredible zest and expression.

Contact: lostnostalgiaproductions@gmail.com

Website: www.lostnostalgia.com

Like what we're doing? Please consider throwing us a dollar into our Patreon page's tip jar!