Defending Your Life

- Review

People have long pondered the hereafter. What happens upon death when one’s consciousness flits to the next dimension? What awaits on the other side? Justice and bliss? Judgement and punishment? Indeed, what is the purpose of existence? The whole point of it all? Defending Your Life somehow answers, subverts, and ignores these questions all at the same time. For, according to the Gospel of Albert Brooks, the afterlife has very little in common with traditional, terrestrial notions of the divine.

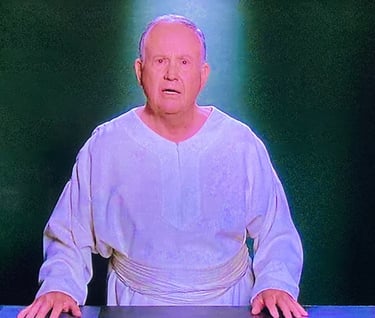

As the film’s triumvirate director, writer, and lead actor, Brooks is the chief evangelist here, trumpeting his vision of a “heaven” that’s not really a heaven at all, but more of a temporary haven—a pit stop—between terrestrial experiences. His character, Daniel Miller, gets hit by a bus in the movie’s opening moments, only to awaken riding an inexplicable tram car alongside hundreds of other groggy, befuddled souls. He’s soon brought to a hotel and told that, once he rests, all will be revealed.

Except, not exactly. Daniel does awaken to learn he’s in Judgment City, the place souls first go after death. Like every recently deceased person, he must now prove he’s worthy to move forward (upward?) via a sort of tribunal/life review process. And more critically, if he fails, it’s back to Earth for another round of base reincarnation. (He’s been there some twenty times already.)

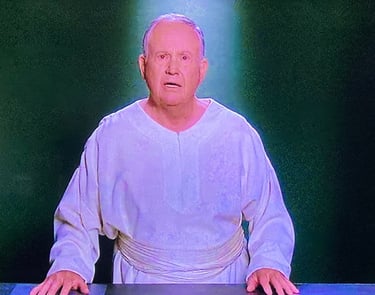

But Daniel is not on his own; like every departed soul, he’s given a kind of spirit guide/public defender—in this instance, the hapless but earnest Bob Diamond—to help convince the presiding powers of his right to move onward. Bob’s opposite is Lena Foster, a perfectly cold curmudgeon of a prosecutor adamant to prove Daniel only deserves more Earth. And she has plenty of unflattering scenes from his blunderful life to make a solid case.

It’s a fantastic premise built on shaky, even wishful theology; no one in this limbo-land seems too concerned with morality or generosity or eternal Truth. When Daniel asks how much money he should have donated to charity, Bob dodges the question, saying only that Dan should have been more generous with himself. In fact, no mention of sin or virtue is ever readily given, only that Hell doesn’t exist and that the Universe works as a kind of hierarchical machine. Does “God” exist at the top? Who knows? No one asks.

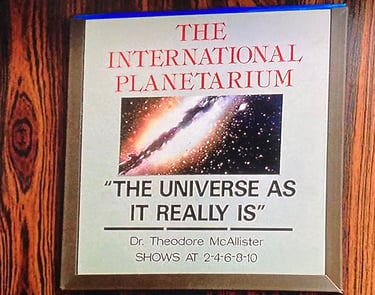

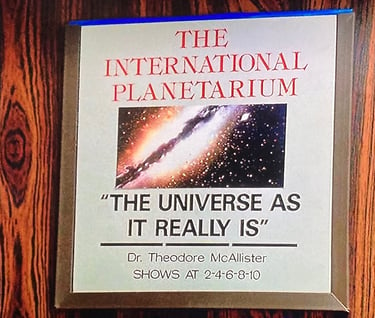

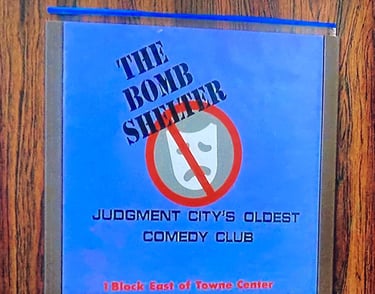

Which is perhaps the movie’s main oversight: the characters are curiously incurious about their surroundings or greater existence. When Daniel sees two advertisements, one for a lecture on the mysteries of the universe, and another for a stand-up comedy show, he chooses the latter, apparently uninterested in delving into the Ether’s heretofore forbidden secrets. Moreover, the film’s notions of “moving on” or “using more of one’s brain” are only cryptically explained. Does transcending earthly life mean becoming a different lifeform altogether, or are humans meant to remain, well, human?

What does matter, per the core chorus of Brooks, is courage. Defending Your Life’s one maxim is Defeat Your Fear; to reach that next plane of existence, nothing matters more than surmounting one’s phobias and traumas, taking advantage of opportunities, and learning to take risks. Acting charitably is fine—maybe even acting badly is fine!—but acting cowardly is unforgivable. By such narrow, one-dimensional standards, were the Stalins and Maos of history also allowed to move on? After all, they do meet the all-important criteria of being brave, taking risks, and capably seizing opportunities as they come. One wonders...and shudders.

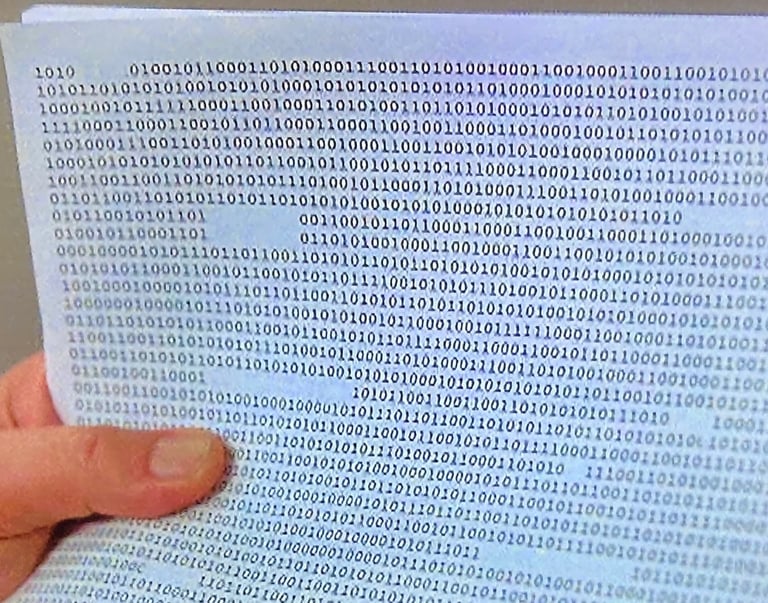

And yet, despite those uncomfortable philosophical holes, the film does offer some sly insights, especially for the pre-digital times of its release. Bob Diamond is shown reading a sheet of binary numbers, hinting that the universe is not only a machine, but a simulation (and by extension, every soul a dynamic, self-learning program). When Daniel orders an omelet, the waitress serves one up instantly as if she had just spawned one “off-screen” like an item conjured in a video game. Even Julia, Daniel’s eventual love interest, seems too good to be true…suggesting that she herself might be a “player”—or an NPC?—planted to inspire Dan to overcome the last of his inner doubts and demons.

Defending Your Life raises more questions than it answers, standing more as a mystery unto itself than a useful primer for life’s deeper realities or existential truths. Who is Jesus? Am I loved? Will I ever see my family again? Is there justice or only delusion in the universe? Instead of offering bona fide enlightenment, the movie simply misdirects, hoping audiences will forget the obvious questions and just accept the bigger message…Believe in yourself! Carpe diem! No pain, no gain! Or some simulacrum thereof.

Such an audience-wary approach is certainly safer. Less potentially offensive. Less risky.

And as Brooks’ own hypothetical prosecutor might someday say…

…indefensibly more cowardly.—D

Daniel's first moments in the afterlife consist of being wheeled out to a tram and then being hauled to a 2-star hotel. This is paradise?

After reviewing Daniel's case, Bob Diamond is concerned. Very concerned.

Very little about ethics or the concepts of good and evil are explored, but Dan does ask about charity. "How much do you have to give? What's the total?" Bob's answer is not unlike what an Objectivist would say: Be more generous with yourself. So much for selflessness.

Daniel's trial consists of watching his life's events as lawyers pick them apart. Two presiding judges observe the whole affair, usually without much comment.

Bob Diamond digests his information via binary numbers--whether this is more efficient than simply using words (in binary language, eight digits equals a single character), the implication is significant. The Universe isn't just a machine, but a program. Or rather, a simulation.

Dan notices two advertisements--one for a stimulating dive into the Universe's secrets, another for a banal comedy show. Guess which one he chooses?

One of the film's funnier bits involves some random souls beholding what they were in previous incarnations. Such is the problem with reincarnation: which "you" is the true "you?"

Contact: lostnostalgiaproductions@gmail.com

Website: www.lostnostalgia.com

Like what we're doing? Please consider throwing us a dollar into our Patreon page's tip jar!