Keio Flying Squadron Review: Shooting Tanuki With Style

Keio Flying Squadron

Platform: Sega CD

Sharp cinematic stills reward the player in-between the various stages. They definitely help bring Rami to life.

The shooter. The shoot ‘em up. The shmup. Whatever one chooses to call the genre, most agree that the category both benefits and suffers from a single condition.

Predictability.

Whether horizontally or vertically oriented, the typical “shooter” presumes a number of tropes and baked-in mechanics: A ship or aircraft weaving through droves of dangerous foes. Huge, devastating bosses. Hundreds of enemy shots. And a host of psychedelic powerups to even the odds.

At its core, the shooter celebrates stress, survival, and destruction—elements that faithfully engage the psyche no matter how many times they’re repeated. It’s a genre drenched in adrenaline, a rotating gamut for anyone seeking to test his meddle. But such narrow aspirations beget a quick dead-end on the evolutionary tree. By the mid-1990s, the genre had reached its peak. Reliably exciting but also rote…the shooter found itself unable to transcend its primitive promise of fast, gratifying action. Whether blasting space bugs or scraping alien entrails, players always knew the basic script. Knew the routine. Sensed the ending. Shoot, move, shoot and move. Shoot to win. What had been a formative movement in the art form (starting with Space Invaders) had eventually become formula. The proceedings predictable, then trite, then simply trivial.

Hence the so-called cute ‘em up, an offshoot that exchanged the ships and heavy artillery of the typical shooter for the winsome and adorable. If the genre had become gripped by its own rigid definitions—by its wanton gauntlets of blaze and barrage—at least this aesthetic change allowed for more comedic sensibilities. A sweeter, sillier veneer. Sure, blasting was still the point, but when the bullets and spells are being dispelled by chibi penguins and doe-eyed witches, everything became a bit more personable. An exploding ship doesn’t draw tears. But a bunny girl getting torched by a tanuki? That might command a laugh.

Enter Keio’s Flying Squadron. It does nothing new and does nothing better than its contemporaries of the era. But it was cute. Wacky. Sassy. Irreverent. Part parody, part satire. And in the early-90s, beholding such nonsense in any genre, let alone the normally staid and unironic shooter, was shocking. Enough to transform an otherwise mundane game into something memorable.

Memorable, at least, had Keio not been released so late in North America, and on Sega’s underappreciated Sega CD platform. As the 16-bit age waned in the wake of the 32-bit revolution, most overlooked the strange game that saw Rami, a cute bunny girl, flying atop her pet dragon to stop a “raccoon” bent on world domination. It’s a nonsensical plot inspired loosely by a Japanese folk tale concerning a rabbit and a nefarious tanuki, and (very loosely) the story of Noah. Only, in this version, that rabbit is Rami…on the aforementioned dragon (named Spot)…facing off against gods and the American military and a hodgepodge of other tacked-on targets sent courtesy of that wacky raccoon (who has an IQ of 1400).

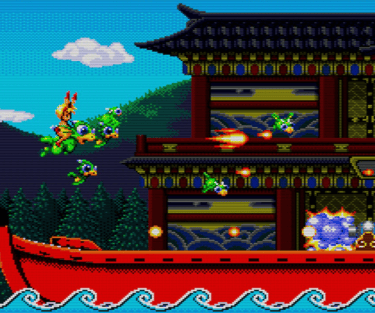

Mechanically, the game is nothing brilliant. Spot’s fire breath can be upgraded across two separate branches—a weaker three-way spread, or a more potent single shot that shoots straight ahead. Baby, “satellite” dragons can also be attained to bolster Rami’s overall firepower, while a secondary attack, from falling bombs to homing dragons, can also be attained. If not for their cutesy pretensions, it’d all be pretty boilerplate fare for the genre.

But cute is the point here, and whatever might be lacking in the mechanics and level design is redeemed through the sheer fervor of the game’s presentation. Tanuki rowing through the air in little boats. Flying pigs. Giant Kabuki and geisha bosses. A robotic, flame-belching cat. Mechanical turtles and rooster-roosting weather vanes. The levels are also stylized; stage two, for example, is literally presented as a stage, with the water resembling the wavy, wooden constructs seen in classical onstage performances and other art. In some sense, Keio was Yoshi’s Story and Paper Mario long before they were fashionable.

And that humor. Although Keio is wackier and weirder than outright funny, it still bears a charm—certainly a personality—that stands as a refreshing contrast to the self-serious games of today. The game’s animated cutscenes would have been especially endearing for a time when CD-multimedia was just beginning to emerge. But even now, it resonates in a way modern games can’t, or won’t, capture or invoke.

Keio comes from a time when average gameplay could be buoyed—even redeemed—my its presentation and theme. No one plays Parodius or The Game Paradise because of its clever proceedings—they do it for the humor, the cute girls, the zany what-will-happen-next expectations. Keio owes to the same tradition, entertaining as much through the sheer fervor of its nonsensical world, likable characters, and triumphant soundtrack as its flying and blasting mechanics. It was a time when gamers were more forgiving, and maybe less privileged, fostering a hobby in which a game like Keio could exist.

Like the overarching genre from which it spawned, the cute ‘em up has grown too niche for the mainstream… become too simple, too staid, and in Keio’s case, too politically incorrect for the bigger publishers. In an age where art has become controlled by a pronounced Marxist-esque puritanism, the role of the bunny-girl heroine—or any character of an alluring nature—has been diminished to the brink of extinction. And for that, Keio’s Rami is a decidedly progressive figure despite being a lass tucked in a bunny suit. She’s more at odds with the cultural censors of 2024 than back in the supposedly less-tolerant 1990s.

Like the aforementioned Parodius series, Rami would eventually fade away, with only two more games to her name—Keio Flying Squadron 2 (a platformer) and Rami-chan no Oedo Sugoroku: Keio Yugekitai Gaiden (a party game). The gal has been frozen in wistful limbo ever since, waiting and praying for a shooter-renaissance comeback…and for those social controllers to relinquish their grip and gain a sense of humor. Until that happens, Rami’s best days will remain in the ‘90s.

Niche games then, rare treasures now.--D

Publisher: JVC Musical Industries

Developer: Victor Entertainment

Release: 1993 (JP), '94 (EU), '95 (NA)

Genre: Single-screen Platformer

Keio's charm lies in its many expressive enemies. More than just being targets, they have a certain character...a certain flavor.

Bosses are varied and can get quite outlandish. Note the hamster running inside that mechanical cat.

The game's art style sometimes resembles the wooden, painted stage of a kabuki theater. The game may be a tad staid in its gameplay, but aesthetically, it was ahead of its time.

Full-motion video scenes adorn the game's front and back ends. Although super grainy, they were certainly treats in '95--especially for anime lovers who were desperate for any of that rare "Japanimation" to come their way.

Keio's options are also impressive for their era. As shown in the screen's upper left corner, Spot's hitbox can be adjusted.

Contact: lostnostalgiaproductions@gmail.com

Website: www.lostnostalgia.com

Like what we're doing? Please consider throwing us a dollar into our Patreon page's tip jar!