Hayao Miyazaki. He’s a master animator and world-renowned director and one of the great storytellers of his age. His characters have enchanted generations of fans and are recognized around the globe. The man, seemingly, can do no wrong.

But if the guru could ever be criticized, ever be so lightly reprimanded, it might be on that third point. Though he’s an incredible idea man—a genius imagineer—his storytelling doesn’t always quite match the rest of his talent. Some of his scripts are thin, almost plotless (Shuna’s Journey, Ponyo). Others are the reverse, being either convoluted or slightly obtuse (Nausicaa, Howls, Mononoke). And some are borderline nonsensical when judged with any sense of logical consequence (again, Ponyo).

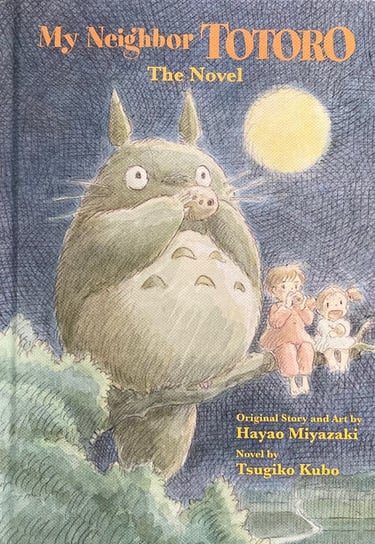

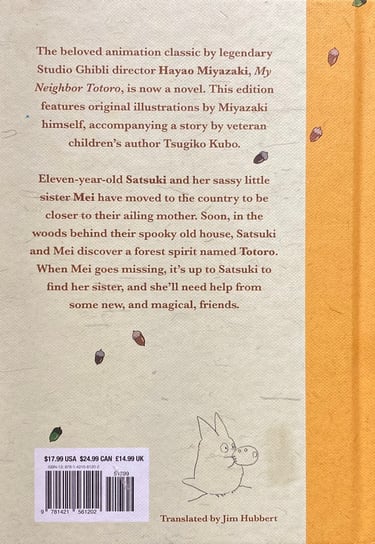

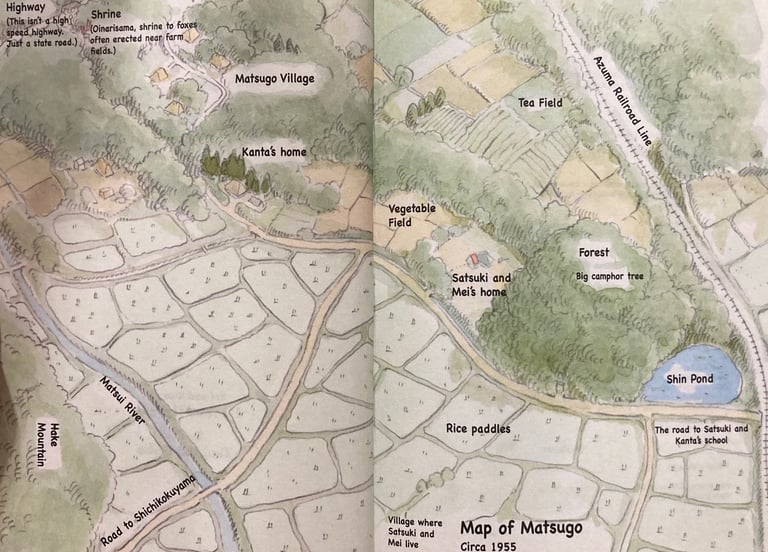

My Neighbor Totoro clearly favors the more slice-of-life side of Miyazaki’s narrative formulations. It’s more premise than plot--more an organic starting point given space to breathe and gel into an endearing tale: To better care for his ailing wife, a professor and his two daughters move to the countryside where they take residence in a ramshackle house at the edge of a mysterious wood. The girls enjoy exploring their new surroundings. And amidst their adventures, they happen upon an elusive spirit—the mythological Totoro.

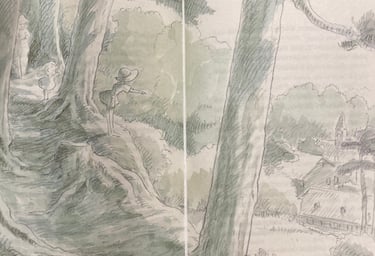

The movie is sweet. Nuanced. Lacks any hint of pretension or contrivance. And is staunchly antithetical to the Epic or Sensational. Totoro might be the featured, lovable star, but he’s rarely there. Rather, the film is about the kids. Of child-like innocence. Of growing up. Of revering nature and believing in the unseen. Of rural versus urban life without a cityscape ever appearing. It’s about keeping a child-like faith. It’s about community and siblings and seeking to be brave. My Neighbor Totoro is essentially plotless, yes. But it’s nowhere near pointless.

If anything, the film’s wistful vibes and strings of meanings are only heightened by its wafty, lackadaisical structure. It’s the characters and their sunny-side setting that matter, both of which evoke a kind of warmth and healing cheer that can’t be told, can’t be heard or held…but only felt by its audience. It’s the sensual over the verbal. The analogue over the digital. The intuitive over the literal. Totoro’s story, in essence, is that there is no plot, only life, in all its shades and fervors. The film is a composite of the human unconscious—of a people, of a time, of an ideal, of Miyazaki himself—transcending the screen. Transcending realities. And settling like the scents of lilac, mint, and mugwort across its mesmerized audience.

The movie succeeds because there is no conventional plot. Miyazaki had the vision and intuition to divine the proper balance between story and sensation, to tell his tale without really saying anything at all. It’s what makes Totoro one of his greatest achievements.

And why the novelization, unfortunately, can’t quite catch that same Miyazaki magic.

Written by Tsugiko Kubo and translated by Jim Hubbert, My Neighbor Totoro: The Novel stays faithful to the original storyline but mismanages the balance, choosing to favor (even belabor) the daily incidentals over the tale’s supernatural thralls. Miyazaki ensures that his moments of the surreal and miraculous, despite their brevity, still punctuate the proceedings with an unforgettable poignancy--being the film's most "realistic" scenes despite their extreme improbability. Kubo tries a different tact, treating the same events in an almost off-handed, trifling fashion--suggesting, perhaps, that the miracles are more akin to dream, of girlhood imagination, than literal happening.

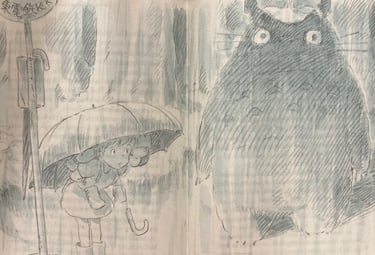

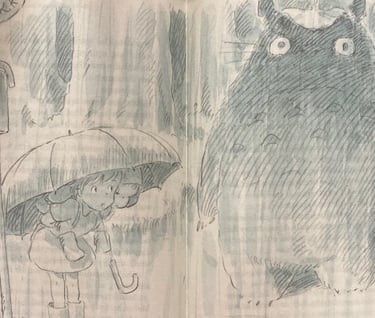

Kubo is at a disadvantage, of course. Her medium of print and page can’t match the elastic antics and watercolorful beauty Miyazaki so capably casts across his theater-wide canvas. How does an author, by dint of text, convey every little snort and squirm and squiggle made by a lumbering, rubbery, yet light-as-a-leaf rabbit-cat as conceived by an animator who knows no bounds? The joys of My Neighbor Totoro, and especially that of Totoro specifically, are the subtle shifts in his reactions and movements. The way his whiskers flick and twitch like the feelers on a crab. The way his invisible lips flap and dip beneath teeth the size of dinner plates. The way each raindrop, as they plop on Totoro’s umbrella, brings a note of increasing delight to the creature’s wizened but playful face. It’d take pages of words and adjectives and metaphor to even approach what Miyazaki depicts instantly on the screen.

So, perhaps rightfully, Kubo doesn’t try. The scenes with Totoro are kept light, and treated secondarily, even tertiarily, to the experiences of sisters Satsuki and Mei navigating an unfamiliar world where luxury is rare and hard work the norm. Their mother, who’s revealed here to be recovering from Tuberculosis, is better defined than her cinematic counterpart. And likewise, the supporting cast has more to do, with some characters tweaked and others outright added, to further contextualize a plot that was barely there before. But the biggest difference comes with the messaging: while Miyazaki lets his opus speak for itself without any glaring premeditated lesson or statement, Kubo draws a clear delineation between the benefits of rural versus city life. The former rewards through toil and the soil; the latter pampers through convenience and superficial pretense. One mode of living, as depicted here, is clearly superior to the other.

Reducing an animated masterpiece, one in which half the joys are stored in the visuals, is probably a losing proposition—one complicated further through an overlapping layer of English localization. Kubo’s attempt to recast Miyazaki's magic spell is admirable but can’t fully duplicate his fizzy, jubilant spirit. But again, how could it?

Nevertheless, taken as a standalone project, or even as a contextual guidebook to the filmmaker’s classic, Kubo’s My Neighbor Totoro boasts its own fuzzy charms. It’s the perfect prayer for those with similar yearnings of escaping a city's suffocation…and finding themselves at rest, at last, in a sea of enriching green.--D