Disney is famous, or notorious, for taking a classic story and then “Disney-fying” it. Sometimes this works well, with the Disney version of, say, Snow White or Sleeping Beauty exceeding their original source material. But sometimes, the original story becomes altered beyond recognition. Frozen, based on the Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale “The Snow Queen,” has virtually nothing in common with the 1844 classic. It might be good…but it certainly isn’t faithful to its supposed inspiration.

And the same can be said for Chicken Little, a movie that converts a five-minute fable regarding a neurotic chicken who believes the sky is falling…into a weird tale of alien invasion and a son trying to win his father’s approval. At least the “sky falling” conceit is still there, if superficially—the little chicken does gets hit on the head with a piece of the sky, which is later revealed to be the reflective (LED?) panel of a spaceship. But naturally, no one believes him at the time, deeming the little goof to be, well, rather cuckoo, as he rings the town’s school bell to alert everyone of the danger.

It’s all absurd, even for a cartoon movie that seems to be channeling The Emperor’s New Groove irreverent style of storytelling over the more regal Beauty and the Beast. Indeed, the film’s early, preproduction concept had nothing to do with falling skies and invading aliens or even a boy protagonist; the original version featured a chick—er, a little girl—whose many phobias have left her practically bedridden. To overcome such debilitations, she heads to summer camp where a very different villain awaits, one who’s essentially a manifestation of all her greatest fears. It’s impossible to know if this story would have been superior to the outlandish version Disney actually released, but the differences are striking…inner demons versus aliens from outer space.

Either way, the question remains the same: why produce an adaptation when it’s really not adapting much of anything? If the intent is to tell a story about a downtrodden boy seeking affirmation from his father and community, why not just make a movie about a kid doing just that—overcoming adversity and believing in himself? Are the anthropomorphic animals, aliens, and “falling skies” conceit really necessary?

The answer is “no,” mostly…except that those animals, aliens, and spaceships make for some easy gags and climactic moments. Most Disney animated movies are humorous, but Chicken Little is a Rolodex of jokes, a reel of flipping laughs usually done at the hero’s expense. The movie is essentially four cartoons stitched together with some narrative glue: There’s the opening in which Little proclaims the sky is falling and thereby sends his town into a mad and wacky panic. There’s the baseball game, in which Little inexplicably redeems his tarnished reputation. There’s the alien ship, in which Little uncovers an “invasion” and, in warning his disbelieving town, ruins his reputation yet again. And finally, the alien attack itself, where the aliens do indeed invade—here, Little and his Dad work together to save civilization. Together, these four segments compose the movie’s fundamental structure. But taken individually, they resemble the cartoon shorts of old, making one wonder if the film would have made for a better TV show—a series of simpler cartoons that would have followed the triumphs and travails of a tiny chicken living in a non sequitur of a world.

And the movie, when seen through a modern lens, does bear a television-esque quality. Completed in 2005, Chicken Little’s animation looks a smidge primitive—in those still-early CGI days, Disney was woefully behind Pixar in terms of both talent and skill, having just abandoned 2-D for the “future” of 3-D rendering. This lack of know-how is certainly apparent in Little’s presentation; although serviceable, some scenes look vaguely unfinished, as if lacking that final pass of needed detail. Environments also seem small and uncanny, resembling, well, sets plopped atop a rudimentary backlot versus being extensions of a real, living society. Even the “filler” characters that populate the backgrounds tend to repeat, as if the film’s budget was too shallow to allow for more. Again, this would be forgivable for a TV production, but odd for a theatrical run.

Nevertheless, when at its best, the film is fun—the aliens’ mechanical walkers, clearly inspired by War of the Worlds, move with a believable clank and an almost stop-motion jank, and the scene in which two of the monstrosities cleave their way through a breezy cornfield is executed with a certain maniacal panache. Other moments, such as Little’s desperate time at bat during a pivotal baseball game, is riddled with clever gags and one-liners. Again, more than a theatrical movie, this could have been an excellent pilot to a Chicken Little TV series.

Rather, the opposite happened. Although a moderate success at the box office (and a huge success on DVD), the movie was quickly brushed aside as Disney’s CGI-skills steadily improved. Just five years later, the studio would score big with Tangled…a movie that exponentially exceeds Chicken Little on every level. Jump ahead again to 2016’s Zootopia, and that gulf in quality widens into a sprawling sea. Compared to these illustrious films, Chicken Little not only seems primitive. It feels incidental. Little.

And too tiny, apparently, to earn a sequel or spinoff or even a mention in the modern parks. Like other animated Disney films of that awkward 2005-2009 era (Meet the Robinsons, Bolt, A Christmas Carol), Chicken Little would be seen as, at best, a necessary experiment for a company trying to match its competition. And, at worst, just a one-note gag—a gimmick, really—stretched barely to 81-minutes. It’s cute. It’s quirky. And now, maybe irrelevant.

And maybe, that's exactly how Disney wants it.--D

The story begins, sort of, like the original fable in that poor Chicken Little warns the community that "the sky is falling." The early twist, of course, is that he was hit on the head by something...just not the acorn that his Dad proposes.

Little's faux pas even results in a disparaging movie made being about him. It's amazing the little guy just doesn't throw himself off of a bridge in embarrassment.

Chicken Little is lucky to have such loyal, if unusual, friends. From left to right: Abby (aka The Ugly Duckling), Runt, and Fish Out of Water.

To redeem himself before his father--the true plot of the movie--Little joins his school's baseball team. And miraculously, at the most crucial moment, during the most pivotal game, he scores an impossible, legendary hit...winning the day.

Redeemed, Little shares a gratifying moment with his father. Dad respects me again! But Little's problems are only beginning.

Unfortunately, that piece of sky that hit Little on the head was real, after all. Except, it was actually a piece of alien technology. And when Little tries to explain this--and the impending alien invasion--his Dad still doesn't come through. Enter Act 3.

The movie has some wacky, if nonsensical, gags. Here, the audience is watching the classic rolling-boulder scene in Raiders of the Lost Ark, only to have the falling water tower from outside smash through the screen.

Foxy Loxy serves as Little's would-be nemesis in the film. But her role is, er, little...by the film's second half.

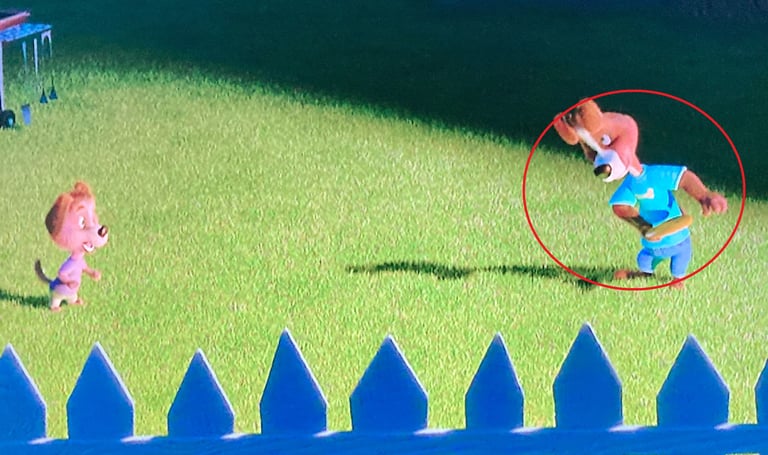

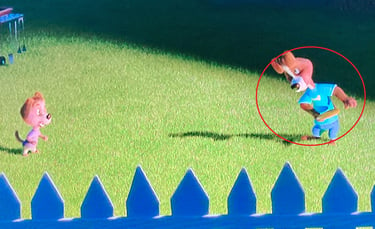

The movie has an inescapably budget feel even for 2005. This is especially noticeable in the background "extras" who seem to be used interchangeably without much attention to continuity. A perfect example is Little's morning sprint to school. The dog in the blue shirt is shown getting on the school bus (a student?), then scampering down the sidewalk, then driving a car...in just a matter of seconds. Later that night, the same character is shown again with his son, the kid on the school bus now apparently a father.

The original version of Chicken Little had a more classic storybook opening with a more faithful premise. This scene was cut from the final edit.

The movie is ostensibly about Chicken Little's redemption in the public eye. But really, it's about the father...who finally recognizes his own failures at the film's denouement.