Mars Needs Moms

Or perhaps...a better plot?

The Walt Disney Company is a media empire that, seemingly, can do no wrong. Unstoppable, savvy, and inexorable, it’s more a force of nature than a typical corporation, pervading every mind and every space. But history tells a different tale—a time when the company went through a kind of anti-renaissance. If the early 1990s brought such classics as The Little Mermaid and The Lion King—some of the greatest examples of 2-D animation and expression—the 2000s brought 3-D, computer-generated works like Chicken Little, Bolt…and Mars Needs Moms. The antithesis, in other words, of what had come just a decade before.

Not that these latter films are outright bad, exactly. Chicken Little is likable in its rudimentary way, and Bolt boasts a similar fundamental charm. But they carry the scent of indecision, of writers and artists more confused that creative. What to do? What to make? What does this newfangled CGI art form really mean for Disney?

The company would eventually figure these mysteries out. But before Zootopia and Wreck-It Ralph, Disney had one more awkward experiment to offer the public. Mars Needs Moms is a fever dream of whim and misery. It’s like an alien abduction dredged from the murky mists of recessed memory. Yes, Mars Needs Moms really happened. And probably, there will never be anything like it again.

…

The plot is in the title. Mars does indeed need Moms. Or rather, a mom.

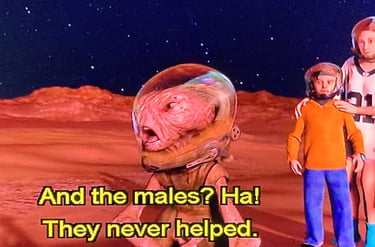

The movie opens with a viewscreen; Martians are monitoring not Earth’s enemies, but its mommies, deciding between potential candidates. And soon, they settle on a woman ordering her son, Milo, to take out the trash. She’s the one they’ve been looking for! Except, in this case, being “the chosen one” isn’t exactly an honor. It’s a horror.

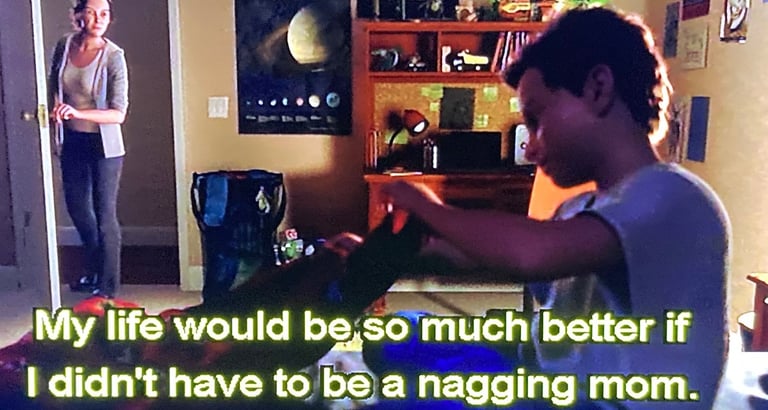

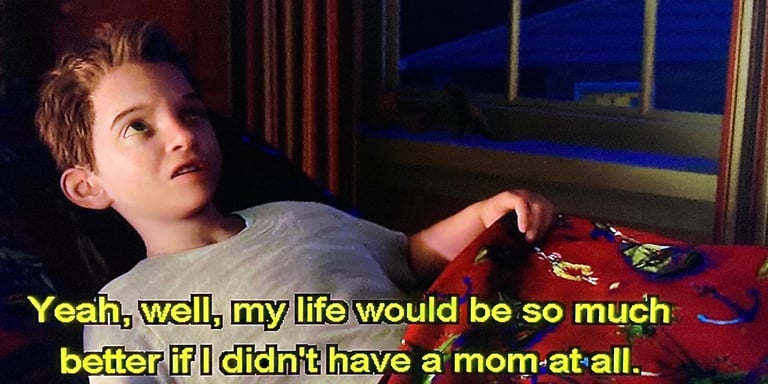

So, that night, the aliens send a rocket ship to whisk the sleeping mother away. But Milo, regretting what he had told her earlier—that his “life would be so much better if I didn’t have a mom at all”—spots her being carried off onto the ship. Like any good son, he follows her onboard, now trapped himself as the rocket zooms home. One wormhole later, he’s on Mars…facing a citadel filled with hostile aliens of the female persuasion.

And that’s just the opener. Milo manages to escape thanks to Gribble, a fellow human who’s been living in hiding for some 25 years. Through Gribble, Milo learns that Mars doesn’t want his Mom so much as her memories, which will be extracted at sunrise to program an array of nanny bots meant to nurture the upcoming crop of Martian hatchlings. But such a download doesn’t just mean a memory wipe, as Milo supposes. It means his mother's immediate death.

Which means, to save her, Milo must endure a theme park worth of falls, close calls, and laser-fire action. For a movie presumably intended for kids, this video-gamey roller coaster of a story isn’t surprising. But what if his original assumption had been the correct one—that the true danger was Mom being memory wiped and thus rendered an unfeeling husk? What if extraction didn’t mean murder, it just meant the cost of her warmth, her empathy, her soul—a woman who looked the same from outside, but was now hollow within? A person who could no longer love? One who, maybe, no longer cared about Milo at all? One who now seemed much like her Martian captors, or worse, the robots they hoped to empower?

What if… instead of Mars Needs Moms…it was Mars Needs Mom’s Brain?

But the movie, despite offering a surprisingly complex landscape of Martian language and culture, is thin on the actual theming. The movie strives to be about love and regret. But really, it’s about run and gun.

…

The movie’s redeeming feature, then, is that it gets ever-weirder; if the main plot is a touch banal, it’s at least buffeted by a series of odd, tantalizing side-stories. There’s Gribble and his secret shame, his traumatic past. There’s Ki, a Martian who, like a flower blooming on the moon, loves color in a world of dead, dismaying gray. And then there’s the Supervisor, the Martian who masterminded such a stoic utopia—her “paradise” is one run exclusively by obedient, unquestioning women. Here, the outcast and downtrodden are the men, who, at birth, are sent to the city’s garbage pits. These poor welps are uncouth, wild, uneducated…but hold the one ingredient their more privileged counterparts lack. Love. The one concept, maybe ironically, the women can’t understand.

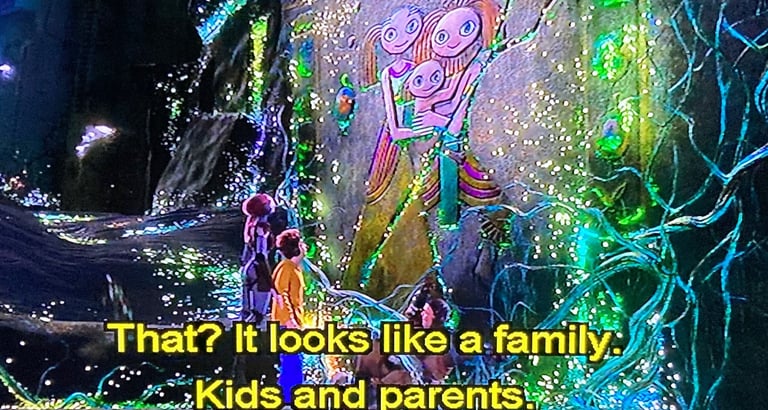

These extra elements grant Mars Needs Mom some needed texture. Gribble, a man-child, finally grows up. Ki learns the meaning of family…and finds an unlikely mate. And the supervisor gets her poetic comeuppance, going from tyrant leader to diaper changer. But the most intriguing piece—that the Martian women have essentially usurped and banished the male half of their race—is barely explored. How did such a coup happen? How was Martian society so easily perverted, the male so easily diminished? And now, with the Supervisor overthrown and the natural order restored, how will these primitive, unpredictable men reintegrate with a society based on humorless conformity?

The movie offers a quick hint in an ending scene depicting some males (along with the Supervisor) caring for some Martian newborns. But is this how Martian society always functioned—that the men did the child-rearing—or is this still some new form of social engineering meant to compensate for that decidedly undermined male caste who, perhaps, can’t do much else? Can the Martian family be revived when such a difference in sophistication, and intellect, exists between husband and wife? Can the sexes unite when Man’s but the happy idiot, and Woman’s the sterile sophisticate? It’s a weird perversion of the feminist conundrum the movie never dares to answer…let alone ask.

…

Such narrative considerations are probably moot, however, compared to the film’s more aesthetic concerns. Mars Needs Moms is an asymmetrical creature—an uncanny reality most will notice long before they ever raise an eyebrow at the plot and its bizarre ideas. The movie, like The Polar Express and A Christmas Carol before it, strives for a level of realism incongruous to the far out farce it ultimately is. Milo and his mother suffer the most, looking somehow off-model despite, as a CGI construct, always being the same model. Gribble, conversely, fares a lot better, looking impressively detailed even by modern standards. Likewise, Ki and her fellow Martians sport some smart designs; despite being barely humanoid, they still manage to be both attractive and empathetic. Like the cat-like Na’vi in Avatar, these are extraterrestrials able to emote and convey some level of sensual appeal.

Environments are similarly uneven, with some hyper-detailed areas juxtaposed with scenes that look surprisingly bland and even half-finished. Perhaps the drab corridors of the Martian’s inner citadel are to blame for some of this; if sterile and uninteresting were the intent, then the artists and renderers definitely succeeded. But it also comes across as generic. Even uninspired.

…

Which leaves Mars Needs Moms in that ignoble position of being less than good but not quite terrible. Like its awkward pre-teen protagonist, this is an awkward film that hasn’t quite grown up. It needs a different script. A different aesthetic.

And probably, really, maybe…a very different audience that what Disney originally intended.--D

The movie opens with the Martian Supervisor scoping Earth for the "proper" mother. Milo's mom is the decided, "perfect" candidate. Why? Because she's seen telling him to take out the trash. What a stellar parental figure!

His mother abducted, Milo jumps aboard the Martian rocket and finds himself whisked to Mars.

The core crux (not horcrux!) of the film resides in this scene where Milo tells his mother he'd be better off without her. It's a relatively flippant, innocent remark that would have been dismissed had Mom not, yeah, gotten abducted by aliens an hour later.

The inexplicable Gribble, who's somehow been living on the red planet undetected for years, explains why the Martians have taken Milo's mother. It's simple: Earthlings, once their consciousness is downloaded into a robotic brain, make the best Martian mothers. Of course!

Ki becomes an essential partner to the Gribble/Milo team, having once seen an old American sitcom that opened her eyes to the wonders of color. She now dreams of a more psychedelic planet; all you need is love, man!

Ki discovers that Martian culture was once the product of this parental unit the Earthlings call a family. And through the might of her smart phone, she convinces her fellow sisters that the nanny bots are so, like, not groovy.

The Supervisor explains her reasoning for destroying the traditional Martian family...which can be attributed essentially to selfish careerism and man hating. Is the movie an allegory, then, for the American West's own stagnation due to the growing collapse of the nuclear family and toxic feminism? What is Mars Needs Moms really saying?

Milo gives his mother an updated, and much better, final line. "Love," indeed, is most precious when uttered by a son.

In the end, Gribble gets his Martian, and Milo gets his mother. Awww...

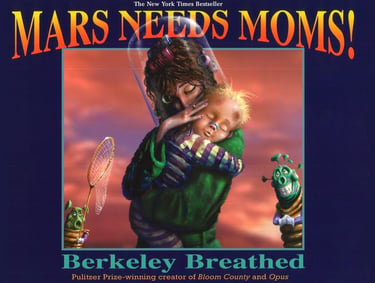

The movie is based, very loosely, on the children's book by Berkeley Breathed. It's a very different story and aesthetic.

Contact: lostnostalgiaproductions@gmail.com

Website: www.lostnostalgia.com

Like what we're doing? Please consider throwing us a dollar into our Patreon page's tip jar!