Gremlins Celebrates its 40th Birthday - When Practical Effects and Puppeteering Were Still the Norms...and Valid Art Forms

Joe Dante's horror-encrusted comedy is now forty years old. It's a grim mixture of sophisticated puppetry and campy laughs--of the cuddly and the ugly united in kind. It's uneven, it's weird, and maybe even better today than when it first appeared.

D

8/22/20246 min read

2024 is a special year! Why? Because it marks the 40th anniversary of the camp horror classic—Gremlins!

Except, “camp” is hardly a fair term to call a film written by the esteemed Chris Columbus and financed by the legendary Steven Spielberg. This wasn’t mere B-movie, low-budget schlock…at least, not exactly. The director, a certain Joe Dante, was in many ways the anti-thesis of his peers, his fame gained not in artful pursuits like Close Encounters or, at least, mainstream fare such as Jaws, but with lower-end scribbles of a more niche, cultish flair. His films didn’t break box-office records, but were still popular. And more importantly—profitable.

So Gremlins was a fusion of three persuasions—of upstart ingenuity (the college-grad Columbus), of money and wise oversight (Spielberg), and of homegrown, kitschy stylings (Dante). Three different worlds had combined to create what can only be described as a crude cartoon made real. A satire on the quirks and pettiness of small-town life. A parody of the typical Christmas, feel-good feature. A horror flick based on cute pretenses.

It was likable. It was maniacal. But was it good?

…

Recently, I went to see Gremlins at my local Cinemark movie theater. The chain was celebrating a flurry of 1984 films during its week-long “Back in ’84” event, including Terminator, Ghostbusters, The Karate Kid, and others. But Gremlins was the one I noticed; it was one of those childhood favorites I remembered fondly despite not having seen it in a long time. For this showing, the film came introduced by a Turner Classic Movies host (sadly, his name escaped me) who provided some tidbits and background texture for the film. Some I already mentioned above, but an interesting aspect I didn’t know about involved the gremlins themselves—they’re loosely inspired by old WW2 superstitions in which military personnel imagined tiny “gremlins” getting into their equipment and causing malfunctions. There was even a Bugs Bunny cartoon—Falling Hare—which depicted one of these mischievous cretins in action, the tyke antagonizing poor Bugs on a military plane. That cartoon, as a neat bonus, was also shown at this showing to further emphasize the film’s source inspiration.

But, although fondly remembered, is Gremlins “good” all these years later? I watched it with fascination, trying to decide; it is entertaining, of course, with some ingenious moments and loving practical effects. But the plot, in hindsight, feels haphazard—almost unfinished—as if half of it was shot before the script had been fully written…or at least revised.

For example, the film’s protagonist, Billy, endures a demeaning co-worker each day at his job. This unlikable blowhard seems perfect for some humbling comeuppance later on…but after he’s fully introduced, he’s never seen again. It’s the same for Billy’s young friend Pete who, after making a number of early appearances (and even being responsible, in part, for the gremlin invasion to follow), is quickly forgotten once the terror really starts.

But the movie comes with plenty of other quirks. It’s not Billy, but his fumbling inventor of a father, who actually narrates the film’s opening and closing sequences…despite the character not participating in the film’s major events. That’s weird. And Billy, despite being the hero, doesn’t do much more than get himself pummeled in the story’s chaotic conclusion. It’s really Gizmo, the little mogwai who inadvertently gave birth to the creatures, who saves the day…along with a lucky sunrise.

What moviegoers have cited as problematic, of course, are the three now infamous rules Billy must follow in being Gizmo’s guardian. The first, “avoid bright light,” is reasonable. And “don’t get him wet” isn’t too farfetched, I guess, assuming the creature never needs a drink of water. But people have long derided its third, most dubious rule. “No feeding him after midnight” seems awfully vague. “Midnight,” technically, is happening everywhere at some point of the day. Tokyo, London, New York…it’s 5:00pm somewhere, so the famous song claims. And how long after midnight must one wait before it’s okay to feed little Gizmo again?

After rewatching, however, I noticed it was the “water” rule that was most inconsistent. Taking place at Christmas, snow is everywhere…and these green cretins are stomping right through it all night, and they’re at the bar splashing beer all over themselves. Is Stripe, the leader of his brood, the only one who can multiply? Can he decide when he “gives birth” to more? The movie never says.

Indeed, ambiguity is the movie’s specialty—very little is explained or reflected upon in the aftermath. Even Billy seems only mildly concerned with the chaos his pet mogwai has wrought in the movie’s closing moments. Does he feel a tinge guilty about all the chaos, all the death? How about his dad, who was the one who brought Gizmo home, and shaky pretenses, in the first place? Shouldn’t father and son at least be outside, offering their help to those who might still be in trouble?

The movie ignores these realities because, in the end, it’s not about the repercussions, it’s about spectacle, the action, the fun. Of cute mogwais being sold as plushies near a toy store near you, and gremlins perfect for the following Halloween. Don’t ask questions—just gobble the food, burp, and move on.

Gremlins is one of my favorite films from 1984. But I wouldn’t call it good. Rather, I’d call it an excellent accident saved by some amazing talent…along with some old-fashioned, movie magic.--D

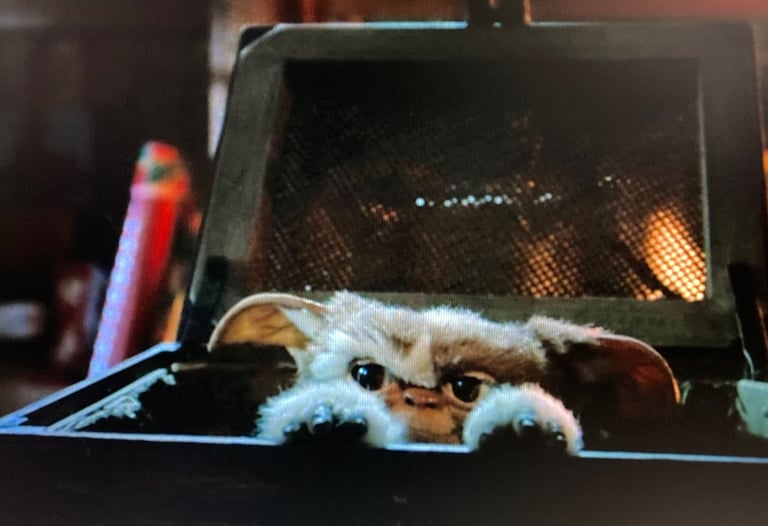

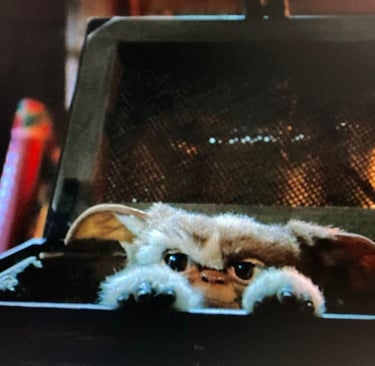

The movie's puppetry is excellent, sometimes even matching the sophistication of Jim Henson's own Muppets. Here, Billy's friend closes his eyes and flares his nose. And with convincing accuracy, Gizmo duplicates his expression. The little puppet is quite the gizmo.

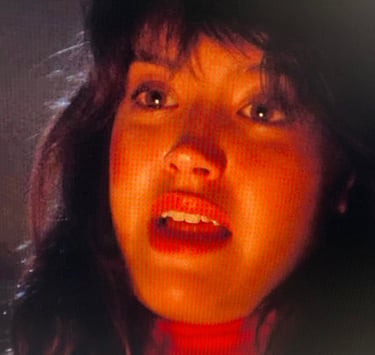

The lovely Phoebe Cates plays, er, Kate, Billy's selfless love interest...with a tragic secret. Late in the film, Kate tells Billy of her late father who, in attempting to play Santa Claus, snapped his neck while climbing down the chimney. Her haunting monologue was almost cut from the final film, but there's no question that Phoebe Cates delivers the scene with heartfelt, heartbreaking conviction. It's the film's best dramatic scene.

Billy's mother almost saves the town by herself, killing nearly all of the initial gremlins hatched out of Gizmo's back. Alas, the leader, Stripe, does escape...giving the movie its second half.

For nostalgia buffs, the film offers plenty of fond, 1984 memories along with some early Steven Spielberg ephemera and other elements that reflect the creators' interests. In Billy's bedroom, the old Warner Bros. cartoon Feed the Kitty plays (a nod to the movie's tacky wackiness mixed with the ridiculously cute) while a Twilight Zone The Movie poster hangs in the back. Later, the mogwai(s) are seen playing on a Donkey Kong Coleco machine. And in the department store, E.T., Bugs Bunny, and Atari 2600 games are all on display.

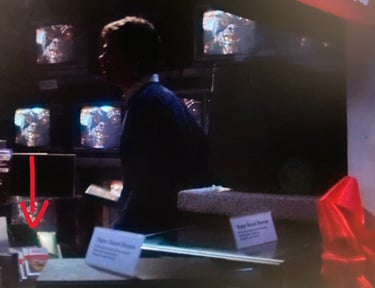

The movie is full of gags--obvious, obscure, and otherwise. Here, the famous time machine from H.G. Well's The Time Machine can be seen in the background...only to seemingly disappear in the next scene. Did it actually work? Is time travel possible? In 1985, we'd know for sure via a flux capacitor and gull-wing doors.

The movie concludes with Gizmo's original owner, Mr. Wing, coming to retrieve the little critter...while Billy's father caps the film with another spiel of narration. For those unaware of the "gremlins-in-the-machinery" myth, his closing words don't make much sense. Indeed, it's a reference/joke I never grasped originally.

Contact: lostnostalgiaproductions@gmail.com

Website: www.lostnostalgia.com

Like what we're doing? Please consider throwing us a dollar into our Patreon page's tip jar!